A freedom of information inquest by Fossil Free USYD has uncovered significant details about the University’s financial relationships with fossil fuel industries. With carbon dioxide concentrations increasing from 310 to 410 parts per million over the last 70 years, coinciding with grave changes to the climate and conditions for human and non-human life, the actions of our influential public institutions deserve careful scrutiny.

The University of Sydney’s (USyd) energy bill totalled $19 million in 2017. Last year, the University lavished $28 million dollars on Stanwell Corporation and Origin Energy, both of which primarily derive energy from fossil fuels. This marks a 43% increase in the University’s expenditure from 2017-18. The University invested $22.4 million in the following fossil fuel companies: BHP Billiton ($9.35M), Woodside Petroleum ($5.9M), AGL Energy ($1.60M), Oil Search ($1.56M), South 32 ($1.30M), Royal Dutch Shell ($1.04M), Whitehaven Coal ($541K), EOG ($400K), CNOOC ($354K), CLP Holdings ($232K), and Santos ($137K).

BHP Billiton was partly responsible for one of the world’s worst environmental disasters in Brazil just three years ago. A collapsed dam spilt 40 million cubic metres of mining waste, which travelled over 650 kilometres from the initial breach, killing 19 people. Royal Dutch Shell, involved in a number of the largest and most well-known oil spills, is no less notorious. In the 1990s Shell wilfully mislead the public about its degradation of Ogoniland and it’s complicity in atrocities carried out by Nigerian military forces, who shielded the company from protestors. A 2017 Amnesty International report revealed Shell was a “central player” in “widespread and serious human rights violations, including the unlawful killing of hundreds of Ogonis, as well as torture… rape, and the destruction of homes and livelihoods.”

Less well-known is Santos, a home-grown energy conglomerate operating in the Asia-Pacific. Santos recently proposed a flagship coal-seam gas project in the Pilliga State Forest of NSW. 23,000 submissions were received in response to their Environmental Impact Statement development application; 98% opposed the project. Whitehaven Coal, another national player with projects in Maules Creek NSW, is widely considered amongst First Nations title holders, local farmers and activists as the most disrespectful towards the environment and the inadequate regulation designed for its protection.

All of these corporations burn huge amounts of greenhouse gases, contributing directly to human-induced climate change. Shell and BHP are among the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitters. Others have 100% of their assets in coal, oil and gas. Most have no concern for human and non-human rights. The University needs to take swift action to counter and delegitimise these companies, not subsidise them.

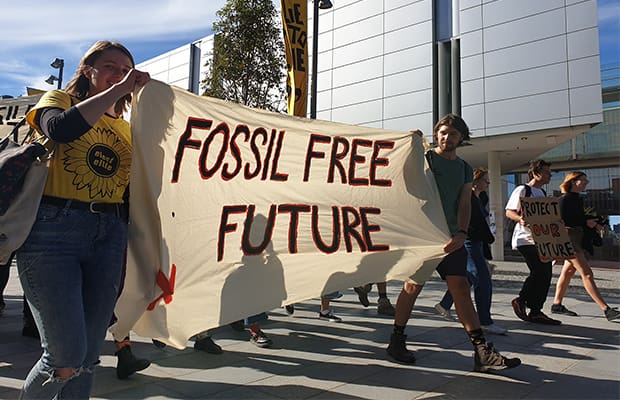

While the University remains obstinate, students around the world are striking, Indigenous communities are continuing to resist theft and usurpation, and workers’ are demanding a just transition to sustainable forms of work. These are not merely minority viewpoints. The Lowy Institute tracked public opinion on climate change for over 10 years. Consistent with a rise in concern since 2012, 59% of respondents in 2018 agreed that “climate change is a serious and pressing problem” and so “we should begin taking steps now even if this involves significant costs.”

Our University is displaying scant regard for this public sentiment.

The science is clear: human action is the most likely cause of observed warming since the 1950s. The rate of this warming is unprecedented. Climate change is resulting in the increased intensity, variability, and frequency of extreme climatic events like droughts, floods, and heatwaves. This contributes to the extreme and escalating rates of species-loss, sea-level rise, and reduced and inconstant rainfall. Those nations and communities that have contributed little to this quandary bear its worst effects. USyd administration are aware of this, yet they continue to satiate their addiction to fossil fuels.

Asking that our University follows the many thousands of other institutions around the world in divesting from carbon-intensive companies is not an unreasonable request. Changing contracts is a simple and effective way to support the renewable energy industry and green jobs. It might seem like an infinitesimal contribution, but that does not vitiate personal responsibility. Bill McKibben, writer and co-founder of the climate campaign 350.org acknowledges that, “divestment by itself is not going to win the climate fight.” But it’s still effective:

“Weakening – reputationally and financially – those players that are determined to stick to business as usual… [is] one crucial part of a broader strategy.”

The divestment movement has already exerted a palpable impact on the fossil fuel industry. It can severely delegitimise a company’s social license to operate and impede its ability to raise capital. Peabody, the world’s largest coal company, filed for bankruptcy in 2016, citing the divestment movement as a contribution to their failure. A Goldman Sachs spokesperson acknowledged that the “divestment movement has been a key driver of the coal sector’s 60% de-rating over the past five years”.

USyd is falling behind its peers. Last year UNSW announced that, from 2020, the University would be powered by 100% renewable energy. Later in the year, UTS signed a power-purchase agreement with a solar farm in Walgett, ensuring that at least 50% of its electricity demand would come from solar. ANU has partly and La Trobe has fully divested. Changing energy providers is a matter of priority for management, and a simple one.

Action from UNSW, La Trobe, and ANU did not come out of nowhere. Divestment was the result of sustained campaigning and pressure from staff and students in each case. Jelena Rudd, one of the indefatigable Fossil Free organisers at UNSW, believes that “campaigns like fossil free are important to persevere with.”

“They serve a dual purpose of achieving a tangible and immediate goal, as well as providing a familiar context for people to grapple with the systemic problems facing society, and the tactics we use to challenge them,” Rudd has said.

Fossil Free USYD is one of many groups that have formed on campuses across Australia to hold universities accountable to the generation they educate.

Our student body and the country deserve better. We deserve management that backs up its talk about sustainability and climate change with action. It is time to ‘unlearn leadership’ — the self-centred, polluting practices of the past — and to work with other universities and organisations in beginning a democratic transition. Our society needs to change, and divesting from the fossil fuel industry is a small, but necessary and practical step, one which USyd should be providing an example.