I have always considered my earliest memories of suffering from Crohn’s Disease to be somewhat strange. Their peculiarity does not arise from the specifics of what happened. In fact, they mostly involve quotidian family interactions that most people would easily forget. What perplexes me about them is how little they actually have to do with the symptoms or physical experience of Crohn’s itself.

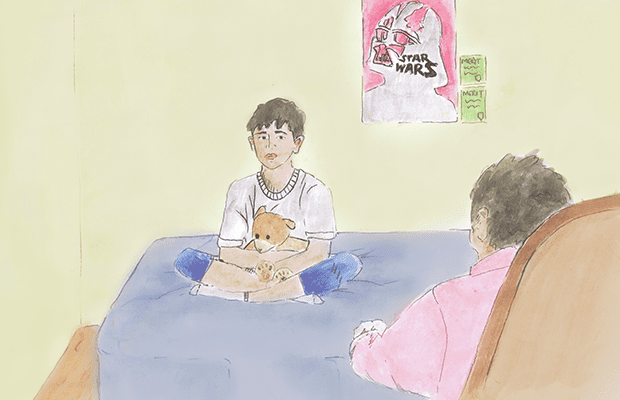

One of the memories which resonates with me most is an interaction I had with my father around the age of eleven. I recall that until that point, like many children, I had maintained a respectful sense of caution around him. We would, of course, spend a lot of time together — he would keenly follow my sports or answer the tedious questions I asked as he drove me to school. However, our relationship was certainly not one which allowed us to be emotionally uninhibited around each other. One day shortly after my Crohn’s diagnosis, he came to my room and sat on a chair opposite my bed. There was an unfamiliar tenderness about him, which at the time I couldn’t entirely comprehend. After a few lingering moments of silence, he asked me how I was feeling and if there was anything I wanted. We exchanged a few more words, he gave me a hug, and then gently walked out of my room.

Eleven years later, while I’m visiting my parents on the weekend, I share this memory with my mother, explaining how odd it is that this is my first memory of Crohn’s. To my surprise, she begins to instantly tear up, looking away as she tells me I won’t understand. “When your child is suffering like that… it’s worse than anything you could go through.” I speak to my father shortly after, asking him what it was like in the early stages when my Crohn’s symptoms were at their worst. The pain hasn’t quite left his voice as he recalls his fear and despair over the horror stories he had read on the internet. My mother later tells me that although he couldn’t quite articulate it at the time, it was incredibly emotionally difficult for him.

To hear my parents recount that period is a little disorienting. When I was younger, I had very little appreciation for the magnitude of what I was going through. I was certainly in a lot of pain, but as a child, that pain seemed transient. It never caused me to dwell too seriously or attach any sense of meaningful emotional disruption to my condition. For me, being unaware of what Crohn’s really was or its long-lasting consequences, my illness simply meant a day off school every once in a while. I have no memory of the tense discussions in the consultation rooms as each new treatment seemed to fail. I can’t even recollect fragments of the debate over whether parts of my intestine should have been surgically removed. All that lives with me from that period are snippets of family interactions and a sense of frustration over the quality of toys in Sydney Children’s Hospital’s waiting area.

As I have gotten older however, I have slowly been able to make more sense of my disease. I often see my specialist alone, make many of my own bookings, and take an active role in monitoring my condition. Naturally, the transition into adult treatment has been empowering for me in many different ways. Paradoxically though, the more I begin to understand Crohn’s disease, the more I’m troubled by a persisting sense of uncertainty.

My experience of suffering from a chronic illness is undeniably made easier by class privilege. Unlike many people around the world, I’m fortunate to have family support as well as access to proximate and affordable healthcare. Unfortunately, though, the fears and anxieties of chronic illness remain enduring. Each small instance of pain or mild sickness brings with it a sense of panic that I may be falling out of remission. Any thought of the future inherently involves a contingency for my symptoms worsening. In stark contrast to my childhood, it’s incredibly difficult to simply leave Crohn’s out of my mind.

The uncertainty of chronic illness doesn’t confine itself to my physical condition either. It means that I’m often left yearning for certainty in other aspects of my life. It makes me a little guarded in social interactions, perhaps in the hope that a stoic facade will allow the world to see that I haven’t let this disease get the best of me. In my personal relationships, I am forced to seek reliability and comfort in ways that many of my peers are not.

Ultimately, though, I’ve learned to make my peace with the uncertainty. I know that Crohn’s will be a permanent fixture in my life. But so too will my mother accompanying me to every infusion I have, or my father awkwardly (but nourishingly) checking in on me. I know my closest friends will continue to support me and that my sister will crack a joke when I’m feeling down. For now, at least, that’s really all the certainty I need.