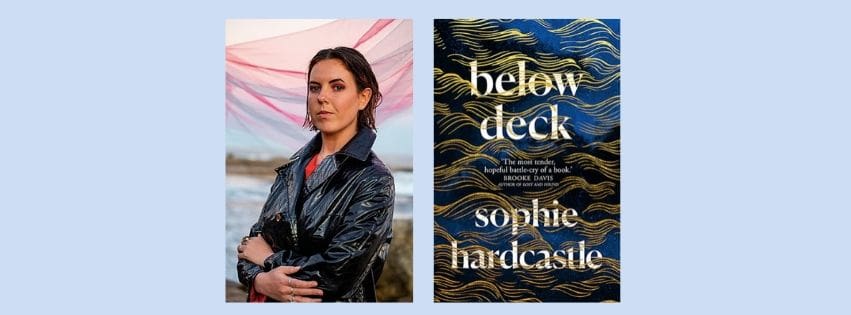

Below Deck is a moving, poetic new work by Sydney author Sophie Hardcastle. It’s unlike anything I’ve ever read before, engaging with the parallels between the destruction of our natural environment and the sexual and systemic violence experienced by women in a novel and compelling way.

I spoke to Sophie earlier this month, shortly after the release of Below Deck.

—-

Madeline Ward: Hi Sophie, thanks for your time! To get things started, I hear that you’re a University of Sydney alumni. What did you study whilst here, and how has it shaped what you write?

Sophie Hardcastle: I studied visual arts, when the SCA (Sydney College of the Arts) campus was at Rozelle. I did my undergrad there, and then my honours — all in painting. I think it shaped the way that I was writing, in that the content and subject matter that I explore in Below Deck was what I spent my honours year exploring through visual art.

I did a residency in Antarctica to research my novel, and then when I came back to do my honours year at Sydney Uni I explored Antarctica as a place, through my paintings. The novel is about sexual violence, but it’s also about the way that the exploitation and oppression of women has so often paralleled that of non human species and entities. The way we think about the environment has so often been linked in inescapable ways to the way that we think about women. I explored that in paintings for a whole year before I started exploring the same topics in writing.

MW: Parts of Below Deck parallel elements of your own career — do you find that drawing from your personal experiences has made your work more relatable?

SH: I’m quite a firm believer in writing what you know. That can often be in a very abstract sense: I did an interview recently for Below Deck, where I was asked the same question. I feel like when you’ve lived something through your body and your senses, for me personally it’s much easier and much more authentic writing about those experiences. I don’t think I would have written about sexual violence in the same way, had I not experienced it. I do really rate authenticity, even if it is in fiction. The novel was well researched in that a lot of what Oli does and where she goes was inspired by trips that I intentionally did so that I would know what that landscape smelt like, and tasted like and so on.

MW: In Below Deck, Oli has synesthesia, which affects her perception of the world around her, and in turn the readers. Why did you choose to include this in her character?

SH: I have synesthesia, and I hear sound in colour. When I went to Antarctica, listening to the glaciers carving, I saw colours that I’d never seen before. In my experience in the Coral Sea listening to whale songs and whales singing underwater I experienced colours that don’t physically exist in the real world. When I came back and I was doing my honours year after those two trips, I was very much trying to work out how I can tell the story of these different spaces and different landscapes through my visual arts practice. I had all of these recordings of the sounds of these landscapes and then I was painting icebergs, glaciers and open oceans in the colours that I heard them in. Having explored these places through a visual arts practice for a year, when I came to write the novel it only made sense to me to carry that through, and keep using my synesthesia in that way.

So much of the book is about who gets seen, and who doesn’t, and whose story gets heard and whose story doesn’t. I thought it would be an interesting way to see something that is so commonplace — sexual violence is an epidemic — and I wanted to show that through a different angle. Using synesthesia and writing Oli’s experience of the world through colour was a device I employed because it was a better way for me to show the scenes that are rendered very common, or that we see in the media — in a different angle. It’s also just a very natural way for me to write, because that’s the way that I perceive the world.

MW: Oli travels and experiences and experiences extreme environments: from the open ocean, to the Antarctic, to even hearing of Hugo’s work with deserts. To me, this made the upsetting banality of her experiences with sexual violence all the more stark. Do you find that communicating the everyday nature of sexual violence is more effective when contasted with such environmental extremes?

SH: The way that the different men function was to show that Mac and Hugo — who have this immense respect for the world around them, and they understand that entire ecosystems depend on each other and that we don’t exist in isolation — are two examples of men who extend their sympathies beyond the human experience to empathise and sympathise with non-humans. There’s Hugo’s work with deserts and Mac’s understanding of the ocean and sailing as a form of listening, and then in stark contrast you have the father who is the head of an oil company, and all of the boys in Sea Monsters who have utter disregard for the world around them and treat it as if they’re on a hierarchy, sitting above everything else. That then directly parallels the way they treat women in the book. A lot of the stuff about the environment and its exploitation, and climate change, was really me trying to find a way to communicate that in a way that moved people, because I believe that if we were purely rational beings we wouldn’t be as deep in this [climate change] as we are. I was trying to use the book as a way to speak about these issues in a way that is accessible.

MW: What I found most compelling about Below Deck is that it portrays the full scope of sexual violence — from Oli’s experiences at sea to those with her first boyfriend Adam — it really interrogates our societal understanding of consent. Especially when Cam asks Oli if she was raped or not, and she replies that it was somewhere in between. Why did you decide to take that particular direction in writing it?

SH: I felt that it was missing, in a lot of the literature that I had read. I didn’t want to do it to fill a space as such, it was more that 85% of survivors and victims of sexual violence — we know our perpetrators. This idea of it being a stranger in an alleyway or someone who is not known to us makes us think that sexual violence exists somehow outside of society and that its not as commonplace as it is. I really wanted to write a scene in which it wasn’t clear cut, because I want the reader to have to interrogate themselves and ask where the line is, because the borders are watery, and at what point did he cross it? I think where things are clear cut or black and white you miss out on the nuance, and you don’t get to interrogate where the line is. We talk about the grey area of consent and yet it doesn’t mean that it’s not a problem. I wanted to show that this still haunts us, that the grey area doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s not as severe.

MW: I think what I loved most about the book is the solidarity between the women within it. Oli forms really strong relationships with Maggie, Natasha etc., and it seemed to me that the greatest love stories in the novel are those of friendship, even between Oli and the men in her life. How important to you was it to emphasise the importance of friendship over romantic love?

SH: I think the biggest thing that I didn’t want to do is write a book where she finally meets a good guy and he saves her. I wasn’t drawn to that, because I feel like we’ve seen it — and I feel like it’s so unrealistic. When they have that scene when they’re in Antarctica and they’re all sitting round the table, sharing their stories. I thought of the idea while I was in Antarctica that was like — we’re so fascinated by ancient glacial ice because it’s full of all these tiny pockets of air that have all these stories in it of distant or past worlds. I loved this idea of glaciers carving and all the stories in those tiny little pockets of air then going back into the sea, like a swirling pool of stories. I imagined all the women shedding their stories and things that were frozen inside of them melting and mixing together. So often we do survive sexual violence by speaking to the friends in our lives, and that’s what gets us through. I really wanted to hone in on that, and not have a romantic relationship save the day and make everything fine.

MW: I think it goes without saying that I really enjoyed this book, and for the most part I found it really relatable. I think where I struggled was with Oli herself — Oli, as the daughter of an incredibly wealthy family, who is highly educated, studying finance, seems to me to be the same sort of white, wealthy woman that dominates our societal discussions around sexual violence and rape culture. Where wealthy white women dominate the headlines, and the issues that affect women of colour or working class women are largely sidelined or ignored, why did you choose to write a character that is already so visible in our discourse?

SH: I’m a middle class white woman, and I don’t think I could grasp the nuance of what it would be like to be sexualised, and experience sexual violence and racism at the same time. I think there are so many incredible women of colour that would write that and have the nuance and understand that because that’s their lived experience. I think there’s something to be said for researching characters, but I didn’t want to write through the eyes of an experience that is that different to mine. Oli is white because that’s my experience, and I didn’t want to take up the space where so many women would be able to write that story for themselves. I didn’t want to co-opt that story. This book speaks to experiences of sexual violence but it doesn’t speak for every woman, and it doesn’t speak for every victim and survivor of sexual violence. It’s a very specific experience, and I hope that when people start talking about it they don’t generalise or universalise Oli’s experience, because it is her experience as a white woman, and that would inevitably differ if she was a woman of colour or if she was indigenous. So I really hope that when people talk about it they won’t talk about it as being a book for all women or all young women or all millenials, or anything like that. I wanted to write an experience that I knew, and that I could grasp and do authentically, but it would be totally unrealistic for Oli to be interacting only with people who are white, cisgendered and straight, so I tried to populate her world with diversity, but without co-opting the experience of someone else in first person.

Below Deck can be bought online. For information on Sophie’s other work, see her website.