As an historian with twelve books under her belt – everything from a biography of the polarising poet James McAuley to an exploration of a sex scandal between a staff member and student at the University of Tasmania in the 1950s – challenging or controversial topics do not seem to intimidate Cassandra Pybus. In her latest book, Truganini: Journey through the apocalypse, Pybus turns her eye to Truganini – a figure believed for far too long to signify the extinction of Tasmania’s Aboriginal population.

Truganini’s story tells a bigger story about Australian history. Common themes in our history form the backdrop – violence, dispossession, environmental change and Indigenous land management practices. The way Pybus matter-of-factly references this context suggests the historical profession has gone a long way towards recognising these facts as fundamental. She is unafraid to use politically-charged terms such as “guerrilla fighters” and “paramilitary organisations” to describe Aboriginal resistance to the theft of land, women and resources.

But these conflicts never overshadow Truganini’s story. This was exactly Pybus’ intention, she tells me on the phone. “The temptation of course is to foreground that stuff because again this is the sort of story we now find that we want to hear – they weren’t savages after all and they could farm… The story we always want to hear about them is that they fought back. We are never so interested in the accommodations that they make in order to live, in order to have families, in order to survive.”

Citing the labelling of the Aboriginal man Wooredy as a resistance fighter at one local gallery, Pybus asks: “Why do we have to make them fighters? What’s wrong with trying to survive? What is wrong with trying to keep your family together? What is wrong with making adjustments to a world turned upside down?”

This process of prioritising violent resistance above all else “dismisses anybody who doesn’t do that. So you elevate certain sorts of people as opposed to other kinds of people or else you just lie about them and say they were great resistance fighters. That’s the issue that Truganini is up against all the time. You could never argue that about her. She gets short shrift because she can’t be turned into a warrior who took up arms against the settler class.”

On the phone, Cassandra Pybus comes across as bold and forceful in her views; opinionated while still firmly grounded. This is perhaps thanks to her non-traditional career trajectory. After completing her PhD, Pybus moved into writing nonfiction narratives based on historical research. From 1989 to 1994, she was editor of the literary magazine Island. “When the government introduced the Australian Research Council [ARC] professorial fellowships for freelance intellectuals – people who weren’t tenured academics – I applied for one of those.” She ended up first at the University of Tasmania. She was attached to the University of Sydney until 2013 when the ARC professorial fellowship program was disbanded, at which point she returned to being a writer. As Pybus explains, “I’ve basically just been a writer and for 12 years I got paid an academic salary to do what I was doing off the smell of an oily rag before then.”

Pybus appears a maverick in the historical profession – at once old-fashioned in her approach to writing history and revolutionary at the same time. She is unafraid to critique herd mentality. While Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu has become a bible for many Australians, Pybus takes issue not with the evidence or arguments in the book – indeed the careful, Aboriginal management of land with fire peppers the pages of Truganini – but with the specific use of Eurocentric nomenclature including agriculture and farming. “I’m not actually interested in making political points about that”, she states during an aside.

To take another example: Pybus detests the academic scaffolding of footnotes, and in Truganini: Journey through the Apocalypse footnotes are noticeably absent. “The general reader doesn’t much care for footnotes, I can tell you”, she says. While her books are aimed at a crossover audience both general and academic, she prefers to be published by trade presses like Allen & Unwin rather than university presses.

But Pybus has more complex reasons for treating the academic world with suspicion. It is not simply an issue of accessibility and readability. “My view is that these are my sources. I’ve been doing history for 50 years. If you wish to dispute with me about what I’ve said here, you go and do the work yourself and then come back and argue with me. Is this not a reasonable position? … [footnotes are] a scourge because people just work off everybody else’s footnotes. You get to the point where nobody’s been in an archive for the entire time of their academic career… This is just a way of perpetuating a particular kind of narrative about the past. The people who really make big leaps and make changes have gone into the archives and done it themselves and come out with a different answer – a different narrative entirely.”

She describes to me walking into a recent Australian Dictionary of Biography seminar at the Australian National University recently and making a speech about these worryingly restrictive trends in current historiography. According to Pybus, “you could hear the gasps in the room.”

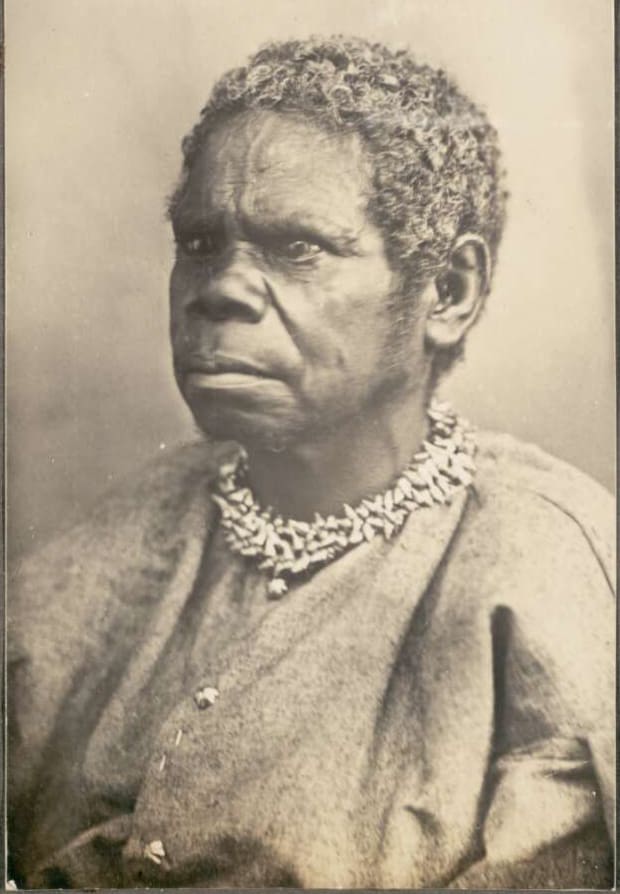

Just as it takes courage to poke your peers, it takes courage to take on Truganini’s story. Telling the story of someone doubly silenced in the archives – as both a woman and an Aboriginal person – is no easy task. There is a limitation in the number of sources available and a scholarly necessity to decode what sources exist.

So much of what we know of Truganini, we perceive through the lens of missionary George Augustus Robinson – the supposed and self-described conciliator with Tasmania’s Aboriginal communities – who kept a detailed journal throughout his life. Pybus tells me that he was “an inveterate writer and observer” but one who was also about “self-aggrandising himself and his extraordinary mission of going around Tasmania and rounding up all these Aboriginal people” for resettlement in the Bass Strait. In Truganini she goes as far as claiming his journal entries are “little more than imaginative constructs”.

Indeed, if we read settler accounts at face value, we fail to hear what Inga Clendinnen has termed the “authoritative British voice-overs interpreting… actions”. These “voice-overs” drown out and mistranslate the dialogue of Indigenous actors. Ann Stoler, meanwhile, has famously demanded we reconceptualise archives “not as sites of knowledge retrieval but of knowledge production, as monuments of states as well as sites of state ethnography… as cultural artefacts of fact production.” Historians must therefore read against and along the “archival grain”.

Pybus seems well-equipped to do so, noting in Truganini: “Robinson was fictionalising his charges into the parts he had made for them, miraculously transformed from nomadic hunters into meek Christian serfs.”

So it is a bumpy path as we walk behind Truganini, tracing her steps. We never walk alongside her because we can never truly know what she feels or thinks. At certain points, where there simply is not enough source material to know what happened, the narrative glosses over years in the space of a few pages.

But even so the biography is thorough. Pybus rises to the challenges by presenting a nuanced, frequently moving, account of Truganini’s life.

When the narrative allows it – usually while painting Tasmania’s rugged landscapes – the prose is vivid. This backdrop shimmers and breathes, forever shaping events as if a character in itself. “Half buried in the sand, uprooted stalks of kelp are like splashes of dark blood against the white quartzit, ground fine as talc. Tendrils of kelp flounce lazily in translucent shallows that gradually deepen to turquoise, turning Prussian blue at the horizon.” So begins the preface. “I would love to be a fiction writer but that’s not where my strengths lie”, Pybus remarks to me modestly.

The strength of Pybus’ writing resides, perhaps most importantly, within understatement; within the matter-of-fact descriptions of intense violence, heart-breaking trauma and inspirational resilience. This subtle style of writing is, of course, partly a necessity. Pybus avoids implanting herself into the narrative by speaking for Truganini. For her, this is a gross act of cultural appropriation beyond her capacity as a writer and beyond her right as a non-Indigenous woman. But her writing style is undeniably a skill she wields with care.

The multi-talented Tasmanian Aboriginal artist, historian and writer Julie Gough has publicly advocated for Aboriginal people to reclaim their history so that white academics “are not the authors of all our history and destiny”. In the face of frustration like this, some may call Pybus’ dive into thorny, Indigenous issues foolhardy.

Pybus concedes to me that the research process was largely not collaborative with Tasmania’s Aboriginal communities. “It’s not that I don’t believe the Tasmanian Aboriginal community has things to offer in this matter. But I’m an historian and I’m used to working with historical documents and setting myself the task of making the past as real as possible without engaging in myth-making or storytelling based in some kind of imaginative realm.” It could be argued that by placing such emphasis on the written word Pybus is asserting a form of neo-colonial hegemony. But in a region with as fractured a history for Aboriginal people as Tasmania this is, to some extent, understandable, perhaps necessary.

Pybus acknowledges that writing such a book is a “fraught business” but stands by her solo research process. Later she asserts: “As much as possible, as much as is feasible, we have to work with First Nations people… But, again I think that we also have to keep a sense of our own integrity as researchers and writers too. This may be an outrageous thing to say. But I’m really not prepared to give over my autonomy as a writer. My books are my books. I’ll take responsibility for them.”

Her staunch defensiveness over sources appears to have paid off with commentary from all sides favourable. This may have something to do with her depiction of Truganini. “I expected to get pushback, and it hasn’t come… Generally people have been very grateful that this woman’s story has been rescued from all the maudlin mythmaking about her.”

Historians and archaeologists have always intensely scrutinised the history of Tasmania (or Van Diemen’s Land, as it was once known), and Truganini: Journey through the apocalypse is not a project about excavating new sources but combatting conventional thinking.

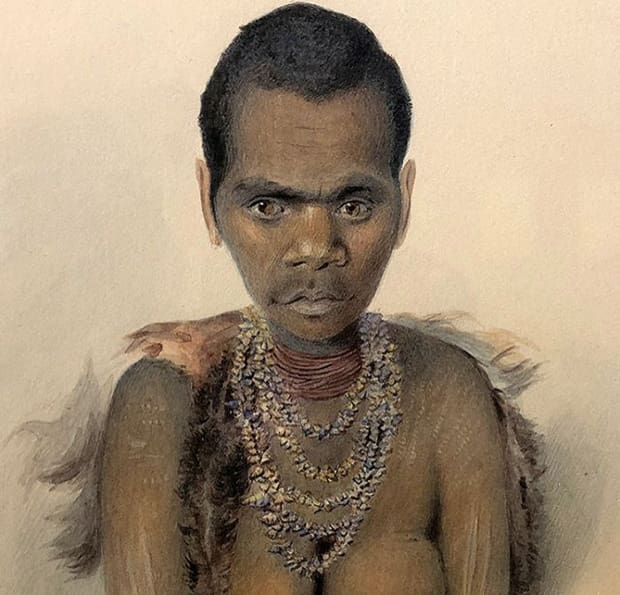

On Truganini’s status as tragic victim, Pybus asserts: “She wasn’t anything of the kind. She was very wilful and clever. She was an extraordinary survivor. She lived to be nearly 70 at a time when women did not live that long as a general rule. She lived entirely on her own terms. The terms were circumscribed hugely by the disaster that had overwhelmed her culture and her people but nevertheless she didn’t become, as might have been expected, somebody’s servant or pet. She entirely was her own woman right up until the moment she died. She negotiated within the extremely limited range of options available for her at various stages in her life the best possible outcome.”

Pybus condemns the “fanciful story that was built on and built on and built on to make the settler community feel much more resigned to the terrible tragedy that had happened… She’s constantly being given to us as this perfect, abject, tragic figure whose only claim on our attention is that she was the last. I don’t have a bar of any of that – not that she was the last or that she was in any way an abject figure of pity.”

There is a ring of the late Inga Clendennin about Cassandra Pybus. Inga Clendinnen’s work showed masterfully how an historian could avoid present-mindedness while utilising interdisciplinary knowledge and cultural theory. She was a self-proclaimed “scientific” historian who condemned what she called “history as patriotism or as group therapy”. Hesitant towards historical fiction like Pybus, Clendinnen, in her quarterly essay The History Question, critiqued Kate Grenville’s Secret River for Grenville’s claim to historical accuracy and truth-telling. Yet Clendinnen was always imaginative (but not imaginary) in her writing and breath-taking in her storytelling ability. In Dancing with Strangers, Clendinnen described a brief “springtime of trust” in Australia’s history of race relations at a time when there was a near fetishisation among history-makers of Indigenous agency.

* * *

Pybus wrote about colonial, Tasmanian history in her first book Community of Thieves, published almost thirty years ago. She has returned to the region in Truganini: Journey through the apocalypse, focusing almost solely this time on the “other side of the frontier”, in what is an intensely personal journey. Pybus’ ancestors were close friends with George Augustus Robinson and complicit in dispossession. They received the largest freehold grant on Truganini’s Nueonne country, owning land on North Bruny Island just outside Hobart. Seen in this way, the book becomes a search for atonement.

But it is also a national story. “This is not just a story of a settler family like mine. This is the Australian story. This is our founding narrative – the brutal dispossession and destruction of ways of life and in its extremity the destruction of whole clans of people.”

This recognition prompted Pybus to include a plea in the afterword for all Australians to support the Uluru Statement and the demands within it. When I ask her if she believes historians have a moral duty to not just acknowledge the impact of their work on contemporary politics but to also engage in politics in their writing and daily lives, she answers in the affirmative. “I think all Australians who are not descended from First Nations people have a moral responsibility to consider what is owed to the First Nations of this country. Historians who perhaps know more than anybody else about that question should be in the vanguard of that.”

Australian historians, or at least those confined within the carceral environment of university sandstone, have not always been at the forefront of reshaping perceptions of Indigeneity. In his renowned 1968 Boyer Lecture, W.E.H Stanner condemned the epistemic violence embedded in Australian historiography. Stanner suggested there was a pervasive “cult of forgetfulness” among historians who, in contrast to archaeologists and anthropologists at the time, arrogantly swept aside Aboriginal history in their research and writing: “…inattention on such a scale cannot possibly be explained by absent-mindedness. It is a structural matter, a view from a window which has been carefully placed to exclude a whole quadrant of the landscape.”

Numerous scholars now argue that what W.E.H Stanner termed the “Great Australian Silence” was confined largely to the professional history academy and to a certain time period – the 1920s to 1970s – when the profession defined itself as a science centred on the rigorous examination of written documents. Historians afforded Indigenous Australians – a non-literate people – little space in their texts but “amateur” archaeologists, museum curators, family historians, journalists and volunteers for local history societies, firmly grounded in place, near obsessed over the material culture and oral history of Aboriginal Australians. In their attempts to foster emotional engagement with the land, these antiquarians developed tortured, ambiguous relationships with country and First Nations people.

This is precisely why historians such as Cassandra Pybus, who refuse to let public perceptions of her as a “scholar” define her identity or her writing, are so valuable. Sometimes we need independent thinkers like Pybus to challenge us, or else our minds remain closed.

Truganini: Journey through the apocalypse by Cassandra Pybus is available now through Allen & Unwin.