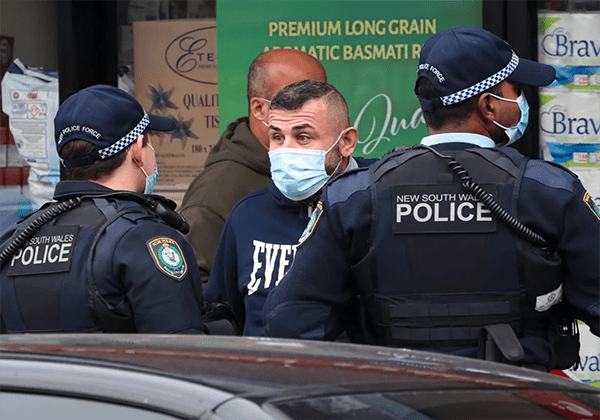

On Friday morning, many of us woke up to the news of a police operation of more than 100 extra officers in Southwestern Sydney. You probably saw news headlines questioning the extra police presence in the area’s communities of mostly ethnic minorities, your friends sharing their outrage on social media, a viral video that shows cops on every street corner in Chester Hill.

Unfortunately for many of us in Southwestern Sydney, the news came as a muffled revving down the street or as the sight of police stopping shoppers at the local supermarket. But to call it ‘news’ implies a novelty about the issue — an unexpectedness. Of course, that’s not the case. It’s written into our history: in the ways we mumble our suburb names when classmates perfunctorily ask us where we’re from, in overhearing conversations from first-years gloating about not having to attend university in Western Sydney, in that prickling sense of discomfort in classes where Western Sydney is yet another case study for criminal behaviour.

This isn’t news to us. In fact, we’re tired of it.

Even before we were labelled as a COVID hotspot, Western Sydney (and Southwestern Sydney, in particular) has long been characterised as a hotspot of criminal activity. In their chapter in The Other Sydney: Communities, Identities and Inequalities in Western Sydney, media scholars Antonio Castillo and Martin Hirst found that media coverage of Fairfield and Cabramatta sensationalises stories about crime, focusing on the problems facing these communities rather than community efforts to address them. As a result, Southwestern Sydney’s criminal image remains “unreformed” in the public consciousness.

The pandemic has forced us to reimagine what ‘normal’ looks like, but it has also made visible how normal it is for Southwestern Sydney communities to be persistently scrutinised. Contrast the video of cops in Chester Hill against images of crowds gathering at Bondi, where there was not a single uniformed officer in sight. On the same day that police issued eight fines to residents in Southwestern Sydney, Natalie Portman and Sacha Baron Cohen were out on an “essential” boat ride in Pittwater, un-penalised. The extra surveillance of the past week is also reminiscent of the scrutiny Southwestern Sydney was under this time last year, when two of NSW’s biggest COVID clusters were named after local businesses Crossroads Hotel (Casula) and Thai Rock (Fairfield).

The resounding message from Deputy Commissioner Mal Lanyon at Thursday’s press conference was that police would have a “very visible presence” in Canterbury-Bankstown, Fairfield and Liverpool. When considering this in the context of these areas’ high immigrant and low income-earner population, it’s impossible not to see the policing as an act of racial profiling. Police have historically viewed these communities with distrust and suspicion, on the assumption that the surveilled subject will inevitably act out.

On Monday, NSW recorded 112 positive, locally acquired cases of COVID-19, with a large number of infections coming from Southwestern Sydney. Just a day earlier, it was revealed that the state’s first death since last year was an elderly woman from Southwestern Sydney who died within 24 hours of receiving a positive test result.

With harrowing figures such as these, it’s clear that we have a responsibility to keep our communities safe by complying with the lockdown rules. But we also have the right to feel safe in our community. The spread of the virus in our area has already taken that away. There is no need for those fears to be compounded by extra police surveillance when there are more viable community-led solutions within reach.

Deputy Commissioner Lanyon also emphasised the increased communication efforts within Southwestern Sydney on Thursday, referring to multicultural liaison officers working with communities and the translation of health messages into a number of different languages. But it’s hard to have confidence in these efforts when the powers that be have little confidence in it themselves and still resort to a ‘visible’ police presence.

Precedent shows that Southwestern Sydney residents are able to comply with public health orders without the watchful glare of the police. Our communities can be trusted to do the right thing – and they should be trusted, if the Premier and the police believe in their own communication efforts with Southwestern Sydney residents. It is not the critical gaze of a policeman watching a potential criminal that will ultimately keep us safe, but expressions of good faith and collaboration between the government and the community.