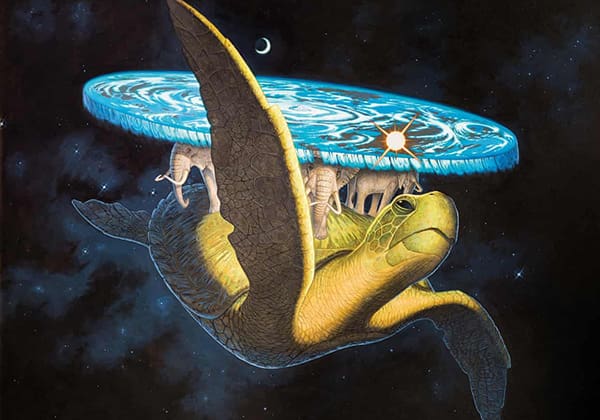

Terry Pratchett has always used space to tell a story. The Disc, the setting of Pratchett’s Discworld novels, is itself a story: a mass of flat earth, sitting atop four elephants, who stand proudly on the back of the Great A’Tuin, who is a magnificent flying turtle gliding through space. It’s outrageous, it’s imaginative, and above all, it possesses a brand of irresistible whimsy unique to Pratchett’s body of work. But if you look closer to examine the cities that sit atop the disc, which itself sits atop four elephants, who proudly stand on the back of the Great A’Tuin, you’ll find that each of them tells a story of their own.

Ankh-Morpork

Ankh-Morpork is a mish-mash of real-world urban centres. In The Art of Discworld, Pratchett explains that the city-state is comparable to the Estonian capital of Tallinn and central Prague, with elements of 18th century London, 19th century Seattle, and 20th century New York. Like many of its inspirations, Ankh-Morpork is a city of immigrants. Trolls, dwarves, vampires, igors, golems, zombies, werewolves, and gnolls — along with a couple of humans — are scattered throughout the city, making it the metropolitan melting pot of the Disc. With each of these fantasy races divvied up into their own slice of the city, Pratchett represents the tension and union of these communities, which is often a focal point for many of his books, through the city itself. Split into the Ankh — the posh end — and the Morpork — the not so posh end — the city-state also tells a story of class divide. The birthplace of Commander Vimes’ socioeconomic “Boots Theory,” there is a world of difference between the exclusive Seven Sleepers neighbourhood and the Shades which is a location with few murders, but several suicides, on account of how suicidal it is to be in the Shades at all. But like the Ankh, a river that runs through the city at a sluggish, toxic pace, class tension fizzles under the surface but is plagued with brutal apathy. It’s the Ankh, unsurprisingly, that captures so much of Ankh-Morpork. Described as “too thick to drink, but too runny to plough,” the river is a lot like the city: it appears virtually inhospitable; yet somehow, people find a way to get by. What lies about the surface and atop the river bed isn’t the entire city though. Ankh-Morpork is not so much a single city, but rather the latest in a long series of prototypes. After every flooding, the citizens of this fine city thought it wise to simply build on top of what the river’s sediment had reclaimed. The Ankh-Morpork of today (or yesterday or tomorrow, because Pratchett’s novels exist in another world with another timeline entirely) is the youngest stratum, sitting atop the fossilized catacombs of an iterative urban landscape. So while it struggles in a state of constant flux, it never truly changes.

Djelibeybi

Stuck in time and stuck in bankruptcy. Two states that stem from its urban design: pyramids. In this desert kingdom, pyramids sucked in time and released the cumulative temporal energy from their capstones into the starlit sky above. The result of which was a kingdom reusing the same day, over and over and over again. With an economy founded on their construction and a religion based on their use, pyramids have informed every aspect of its urban landscape. The necropolis (a city of the dead) occupies Djelibeybi’s most arable land and is second to only Ankh-Morpork as the largest city on the Disc. Like its clocks, Djelibeybi has a culture, religion, and system of government stuck in place. As environmental storytelling goes, Djelibeybi is an obvious analog: the city is stuck in time, society is stuck in time. It speaks to the power of any urban architecture, as a city’s design can often shape its trajectory. One only must examine Sydney’s shoddy planning to see how much power it wields against its residents. But luckily for Djelibeybi, they’ve stopped building pyramids and destroyed the ones that were holding them back. Sometimes, to break free from a vicious cycle, there is no option but to break it.

The Agatean Empire

The Agatean Empire and its capital city are designed around secrecy and censorship. The Great Wall (a parallel for China’s) surrounds the empire with an official purpose to keep barbarians out and an unofficial purpose to keep its residents in. Travel to the Forbidden City, the administrative and imperial palace at the centre of the Agatean capital, and stone walls give way to paper screens. The Agatean people have been instructed not to walk through these screens, but clueless barbarian invaders proceed to tear through them like doors. While the country is insulated by a physical wall of stone, the conventions, and cultural norms, while paper-thin, bind the attitudes and activities of its citizenry. The hermit kingdom spins an obscuring mythos to its residents, one which warns of blood-sucking vampires beyond the walls and barbarians at the gates. But, like the walls of the Forbidden City, they tear under the slightest pressure.

~*~

Terry Pratchett’s worldbuilding is never without purpose. While the extraneous details can seem little more than the whims of an author, they all speak to some greater meaning. While to many, fantasy is shorthand for insincerity, there is nothing insincere about Discworld nor the many ingenious cities that litter its surface.