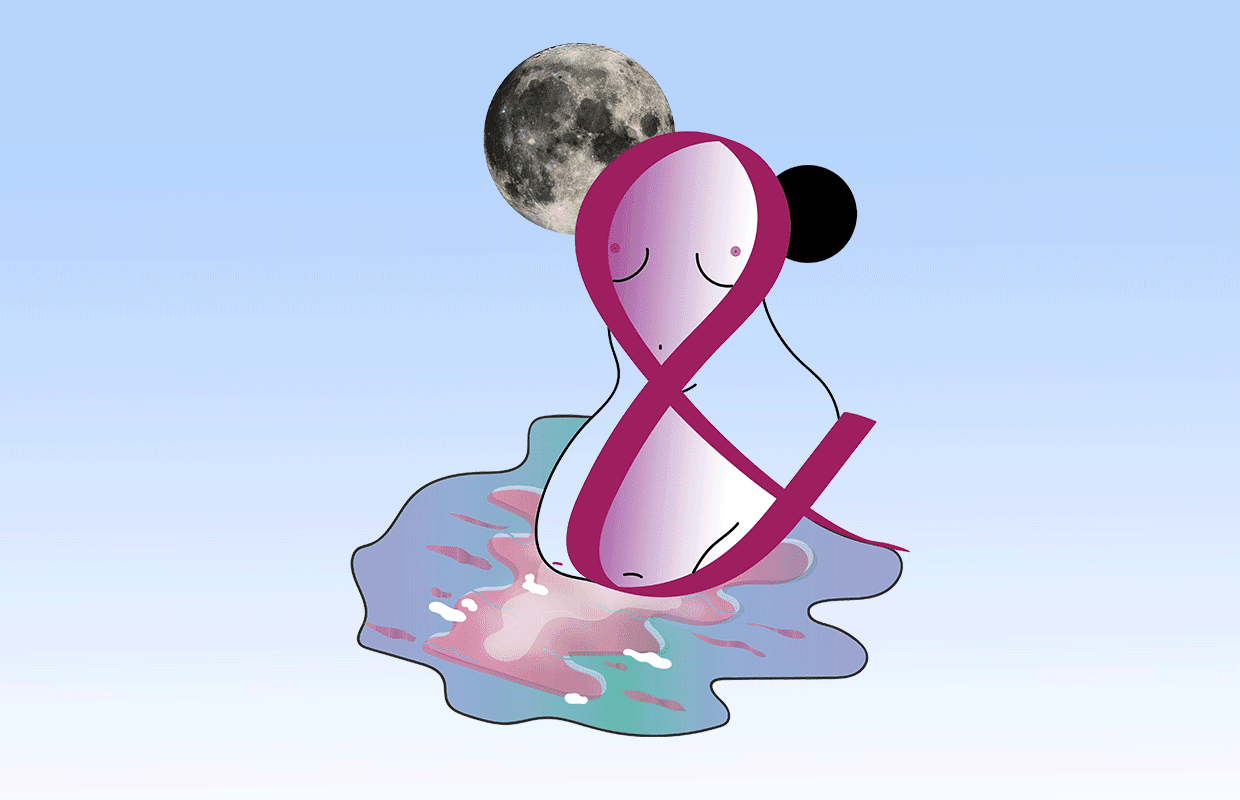

The first line in Aracelis Girmay’s poem “&” begins with the symbol itself: “& isn’t the heart an ampersand / magnet between the seconds of days.” She relates the ampersand to a longing for connection. She calls it a mouth, a muscle. A highway. In an interview with The Rumpus, she revealed that the ampersand reminded her of the quickness in the Spanish “y”. As an Eritrean-Puerto Rican-African American writer, Girmay is a woman of many cultures. For her, and many other marginalised writers, the ampersand represents multiplicity within itself.

“Greedy mouth,

Hungry machine, time

Machine. Round & plum-

ish in its parts, beautiful

animal whose limbs

cross strange”

My fascination with ampersands began with this poem. In my copy of Kingdom Animalia, a single blue sticky-note is eternally stuck to its corner, as a constant reminder of the colossal greatness in something small. I began to look at poetry as more than words, more than feelings. The lines of each stanza were little buildings rising out of the earthly spine; every ampersand, a window. They started to appear in poems of my own — first out of mimicry, then out of necessity. Adhering to literary conventions meant that the ampersand was absent in my formal writing. I associated it purely with poetry, where the words belonged wherever I put them, for whatever reason. Intuition. A gut-feeling: I liked how it looked in print. How it took its shape through softness, a fluid line dancing around twin curves. I also felt quite fond of conjunctions, as the loneliest words, always needing to connect. But there was more to this than an aesthetic choice, and I was drawn to its recurring presence in poems by writers of colour.

In “&”, Girmay draws the link between our lives and the symbol that signifies closeness. The ampersand suggests either disruption or proximity; binding words closer together, while also disrupting the natural flow of letters. Its use remains heavily contested in contemporary poetry. As the only symbol in a line of letters, its effect is unsettling, and sometimes isolating. This feeling of displacement is explored in diasporic writing, often through the use of unconventional literary techniques by authors seeking to disrupt the traditional norm. Although the ampersand can simply be read as a tool of discomfort, its existence in poetry — particularly poetry from the peripheries — is much more layered and complex.

The ampersand began as a character formed through two letters joined together, also known as a ligature. Another definition for ligature is the act of binding, or the thread used to stitch a blood vessel. In its very conception, the ampersand evokes images of the heart and the living body. In its shape, it curls around itself. As Girmay poses, “the heart would rather die than keep its two arms all to himself.” The ampersand therefore represents the middle space between connection and duality.

This notion of multiplicity is central to intersectional feminist theory. In Borderlands/La Frontera, Chicana feminist Gloria Anzaldúa critiques the Western philosophy of a divided self that is manifested through hyphenating one’s identity. The opposing state is the new mestiza, a plural being with the tolerance for ambiguity. It redefines borders in the formation of a unified identity, encompassing culture, gender, race, and sexuality. The ampersand itself is a vehicle for hybridity, illuminated by the language of marginalised writers. It represents a shared feeling through the light of liminal spaces, with an almost unspeakable presence.

In “Immigrant Haibun”, Ocean Vuong simply states, “Sometimes I feel like an ampersand.” Feelings and memories are expressed, not through words, but through a single symbol that is a paradox within itself. What does it mean to feel like an ampersand? From a distance, Vuong’s poems explore migration and collective trauma. A closer reading reveals phrases that are painfully stitched together with a tenderness for life and living. His poem “Untitled (Blue, Green, and Brown)” unfolds on the day of the 9/11 attacks, while also reflecting on the deaths and drug addictions of Vuong’s queer friends. He relates personal and public grief in a way that transpires intimacy. His lines are always sharp with impact in the quietest way, like the tension of a blunt knife pressing against skin that refuses to break: “I only earned one life. & I took nothing.”

Separated by both an ampersand and a full stop, the two contrasting proclamations have a unique relationship. Replacing the ampersand with “and” seems to imply that there is a thought and an action. I only earned one life, and I took nothing. I am this, and this is the result. However, the ampersand does not only allow unity in contradiction; it simply serves no contradiction. The two fragments on opposite sides of the ampersand exist through each other. It is not a consequence, or an action, but a very natural parallel between two individual concepts. The ampersand becomes both the bridge and the water. Visually, the words are placed closer together. Yet there is a feeling of separation in the heavy placement of the ampersand between “life” and “I”. There is the danger of collapse. Always, the danger of collapse.

As a queer woman of colour, my poetry often reflects images I associate with my own life — constructed through fragments and a constant desire to connect. Like the ampersand, we measure both distance and intimacy. The body becomes a site of conflict. Every word, an outstretched hand. Lonely in the most abstract ways. Sometimes, I feel like an ampersand. There are so many questions that follow this sentence. Maybe it answers itself. There is no finality to the ampersand; it is always open to what comes after. We try to make sense of a symbol with no sound, we fold it into language. You read it aloud and the meaning is lost. And, and, and, its lesser self. Sometimes, I feel unspoken. Sometimes, I feel like I am waiting for something that will never come. An unfocused image. No end, or beginning. Still, the running heart, the moving line. Twin lovers holding each other, arms sheltering myself.