In popular memory and historiography, where Indigenous presence is noted at all, Aboriginal and Māori involvement in maritime trades is often celebrated, perhaps with an eye on contemporary political empowerment, as an example of past multicultural success and Indigenous survival. While this recent surge of interest in Indigenous history is welcome, its focus threatens to overshadow an important story of dispossession, trauma and violence.

The cruel irony was that, while sailors treated Indigenous seafarers with more respect than they were otherwise accustomed to and welcomed them as crewmates, as I explain in part one of this article, these same sailors were capable of terrifying outbursts of violence towards coastal Indigenous people.

Writing this history helps us to recognise the limits of national boundaries and binary paradigms in historiography. A number of Aboriginal and Māori seafarers witnessed and partook in violence against other Indigenous communities. Their mobility and intermarriage with settlers and other Indigenous groups simply obliterate notions of a distinctive group of colonisers and colonised, of immigrants and emigrants, of active agents and passive victims.

* * *

Sailors during the Age of Sail were a boisterous, revolutionary lot; however, they were also frequently complicit in grotesque violence. This latter story has largely gone untold.

The Raymond Terrace Examiner, describing the life of a famous local mariner, William Cromarty, reported matter-of-factly that

“The aborigines of the Karuah River were hostile and… the crew had been injured by spears… whilst the brig lay moored. As it was feared that the blacks might try to rush the vessel, at such a time, Captain Cromarty fitted an iron cannon to the brig, and this was loaded with grapeshot. During one desperate affray it was fired point blank.”

While we tend not to associate the ephemeral presence of maritime communities with competition for land and resources and conflict, it was a similar story up and down Antipodean coastlines.

After cross-examining Māori informants in the early twentieth century, the anthropologist Herries Beattie recorded a violent sealing history in New Zealand. In one reprisal for theft and the murder of a white seaman on New Zealand’s west coast, sealers besieged a village and “slaughtered all who did not escape into the bush”. One sealer, Tommy Chaseland, “became a frenzied fiend… he seized a child, Ramirikiri, whose father and mother had been killed, and dashed her head on a rock.” The perpetrators then sailed south and clashed with an innocent Māori community: “The victims… were shot down like rabbits… [the] living were placed in a canoe and towed by the sealers round to Whareko, the next bay south of Milford; and there to finish the sport the canoe with its helpless crew was let go in the surf. The breakers dashed it to pieces, and not a soul was left living.”

The aggression towards the baby may be an exaggeration or a fabrication. Chaseland was a renowned part-Aboriginal sealer and whaler and Beattie may have projected onto this iconic figure his own racial bias about the propensity of Aboriginal people for gross violence.

At the same time, some Aboriginal and Māori seafarers, like Tommy Chaseland, witnessed or themselves partook in violence against coastal Indigenous communities, reflecting a tragic way in which these sailors became absorbed into colonial projects.

On 10 June 1804, the sloop Contest departed Port Jackson for Port Dalrymple. On board was a military detachment and Mongoul – a “native of Sydney”. At Twofold Bay during the return journey, the master of the Contest ventured ashore with Mongoul. Leaving Mongoul to camp near the beach with two soldiers – no doubt to establish amicable relations with local Aboriginal people – a “misunderstanding” arose: “three spears were darted at Mongoul, but were dexterously avoided.” The soldiers fired over the heads of the Aboriginal assailants, successfully scaring them off. However, when relations again soured the next morning, the soldiers fired directly on the natives, killing one. This time the Aboriginal combatants chased the party off their land, throwing spears until the three intruders fled into the sea in their boat.

In 1813, one Māori sailor, “George”, sailed in the Hunter to Fiji where the crew became embroiled in local politics and conflict with the Indigenous inhabitants. In the centre of the action, “George” narrowly escaped with his life.

Bundell, an experienced sailor, sailed with Phillip Parker King on a survey trip around Australia from May 1821 to April 1822. In north-western Australia on 7 August 1821, while exchanging gifts with local Aboriginal tribesmen, the crew was attacked. Bundell pursued the assailants with a broken spear, possibly wounding one.

However, participation in violent encounters with Indigenous groups did not necessarily equate to a loss of cultural heritage or blind support for an all-consuming form of colonialism. Mongoul, for instance, defended land at Stockton Beach, north of Kingstown (now Newcastle), against sailors who were inspecting a shipwreck in 1808.

Chaseland was born in the Windsor district to an Aboriginal mother and white father. By 1823, after years as a shipbuilder, sealer and whaler in the Pacific, he was working as a Māori interpreter and second mate on the whaling vessel St Michael. By the late 1830s, he was managing a whaling station in southern New Zealand, having settled on Stewart Island and married a high-ranking Māori woman called Puna.

* * *

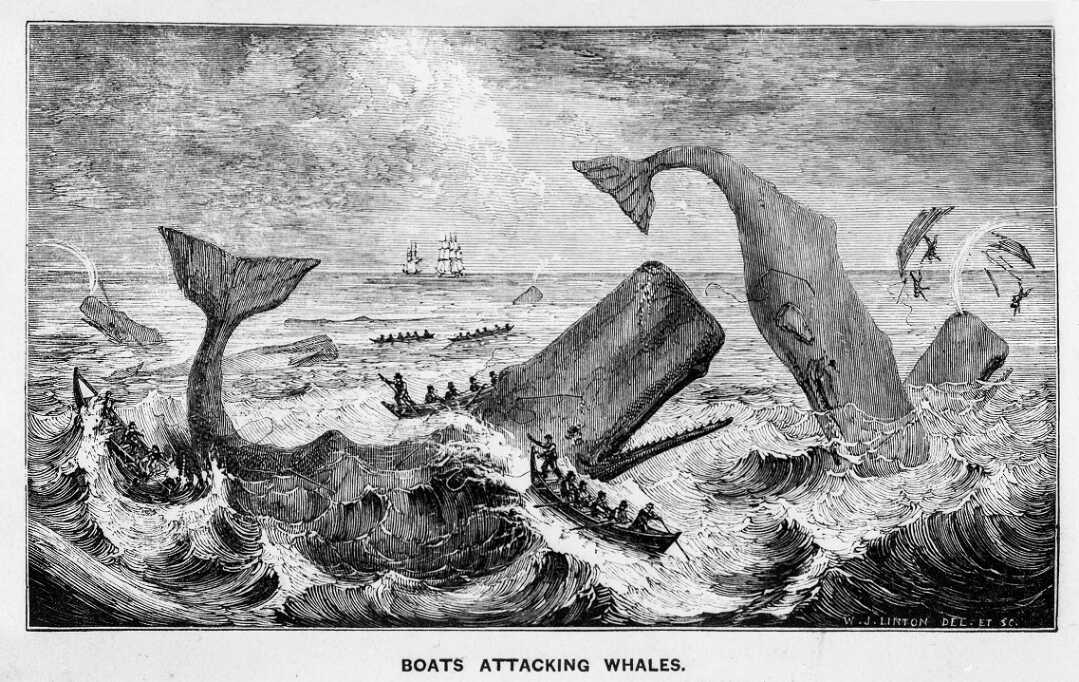

The harsh reality, captured in the satirical lyrics of numerous sea shanties, was that many Indigenous seafarers served in maritime industries renowned for their poor working conditions. Frank Bullen opened his account of a Pacific whaling voyage by describing his yearning in New Bedford for money and the sea. He felt deceived, however, upon realising that he “was booked for the sailor’s horror – a cruise in a whaler”. The sailor Richard Dana immediately recognised a passing “spouter” in 1834 due to the “slovenly look” of its crew, sails, spars and hull.

One sailor, describing first-hand the manufacture of oil on board a whaler in the 1860s, wrote:

“It is as if all the ill odours of the world were gathered together and being shaken up… everything is drenched with oil. Shirts and trowsers [sic] are dripping with the disgusting stuff… the biscuit you eat glistens with oil, and tastes as though just out of the blubber room… you are compelled to inhale the foetid smoke of the scrap fires, until you feel as though it had entered your blood, and suffused every vein in your body.”

Owners and captains often left sealing parties on isolated outcrops and desolate islands throughout the Pacific and Southern Oceans for months and even years without adequate provisions. There are numerous recorded cases of Indigenous seafarers enduring such a fate.

The Aboriginal seafarer Boatswain Mahroot, when questioned in 1845 for The Report from the Select Committee on the Condition of Aborigines, remarked that whaling was “dirty work, and hard work” and that his kinsmen “did not fancy it at all”. Mahroot’s observation may not be applicable to all Aboriginal people (indeed, some Aboriginal whalers such as Tommy Chaseland achieved renown well into the 1850s), but Mahroot himself probably had little choice but to continue whaling in order to support him and his family.

The transcription of Mahroot’s 1845 interview reveals a man desperately trying to carve a path for himself amid trauma, violence and disease. The interview is as poignant as it is inspiring. Mahroot gained the respect of colonial society for his willingness to work hard on the colonisers’ terms. He farmed, fished, sealed and whaled. However, despite his knowledge of tribal boundaries and environmental change around Sydney, Mahroot never underwent male initiation. The Aboriginal community at Botany Bay seemed to distrust him, refusing to allow sick Aboriginal people to visit the Sydney Hospital, despite his encouragement. The very fact that he was the only Aboriginal person questioned for the report suggests his proximity to colonial society. Striding across the bridges between cultures could be a lonely journey.

Some non-white seafarers adopted European hierarchies of race or expressed their own ethnocentrism within the liminal zones of maritime work. Pacific Islander and Māori seafarers tended to look down on Aboriginal people. When Te Pahi and his five sons visited Port Jackson in 1805, they derided Aboriginal people for their nakedness, primitive lifestyle and “trifling mode of warfare”.

Frequent Māori traffic to Sydney undoubtedly fuelled the dissemination of views on Aboriginal people. Historian André Brett argues that unregulated maritime traffic and European understandings of race contributed to an anomalous, annihilationist, Māori invasion of the Chatham Islands in 1835, outside traditional modes of warfare, enslavement, spasmodic migration and intermarriage. These Māori, displaced by the Musket Wars, killed one sixth of the local Moriori population because they viewed the pacifist Moriori as a lesser people than a rival iwi. Despite the array of words available to denote status, Māori applied a new, scornful term learnt from sealers – paraiwhara (“blackfella”) – to both Aboriginal and Moriori people. Paraiwhara indicated a status lower than that of any pre-existing word.

Aboriginal sailors in New Zealand – there were a number of them – were thus doubly displaced. The travelling artist George French Angas noted the presence of an Aboriginal mariner on a schooner plying the Cook Strait in 1844:

“‘Black Charley’… who had heard much of the cannibal propensities of the New Zealanders, was afraid to go ashore for fear of being devoured: he always exhibited the most violent signs of fear whenever any of the natives came on board the schooner, fully expecting they would purchase him for a ‘cooky’ or slave, to be killed and eaten. The young New Zealanders, on the other hand, were greatly amused at the dark colour of his skin and laughed at him… calling him ‘mango, mango,’ or ‘black fellow’.”

* * *

In seeking and foregrounding the agency and humanity of past Indigenous people, who were dehumanised by dispossession, massacre, sexual violence and alcoholism, historians sometimes err. As Walter Johnson argues in reference to slavery and racial capitalism, historians force on the past anachronistic, Western conceptions of liberalism and political emancipation: “By framing their ‘discovery’ of the enduring humanity of enslaved people as a defining feature of their work, by casting their work as proof of black humanity – as if this were a question that should even be posed – historians ironically render black humanity intellectually probationary.” By focusing too heavily on (de)humanisation, we thereby separate ourselves from what possibly defines our humanity – exploitation and violence.

Even the necessity of giving people history for personhood, sovereignty and citizenship is a culturally-specific non-Indigenous viewpoint. Many Indigenous communities, including Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders, as per “The Dreaming”, possessed a vastly different, non-linear conception of time.

Historian David Chappell critiques the binary polarisation of active agents and passive victims in Pacific historiography and the tendency for present-minded historians to upstream self-determination backward through time during an era of decolonisation. Non-Indigenous scholars gifted “agency” to Pacific Islanders while the latter were still clinging to victimhood for their identity. Is this academic emphasis, however altruistic, a veiled form of neo-colonial hegemony over cultural identity? Quite possibly.

Indigenous sailors fill such little space within the national stories of Australia and New Zealand because they embody success neither by colonial standards nor by Western, liberal standards. With their propensity for mimesis, their isolation from easily identifiable, “authentic”, Indigenous cultures and their ambiguous contribution to shipping – a key vehicle in capitalism, settler colonialism and frontier violence – they do not reflect our expectations of what an active agent in history looks like. But perhaps this is not important.

The search for a redeeming quality of agency applies a liberal conception of independence and choice that mattered little to Indigenous men during the Age of Sail. Maritime employment restricted freedom and rights for an oppressed proletariat who saw sealing and whaling as a last resort. The comparison of a maritime career to slavery or a prison sentence was common. White British sailors defined the corporal discipline of the Royal Navy and the omnipotent threat of naval impressment for merchant seamen in racial terms from the late eighteenth century, invoking the plight of plantation slaves to force naval reform. In Antipodean ports, and on ships, the lines between convicts and mariners blurred. But these liminal zones offered Indigenous sailors opportunities and, for some, a refuge and a home.

Maritime employment gave Indigenous seafarers a new way to navigate colonial worlds that did not necessarily involve active resistance or accommodation. Their refusal to conform to colonial norms and expectations was usually financially generative and, strikingly, it resulted in respect, at least among close peers.

But this home was never secure. While mariners might extend a hand towards their Indigenous shipmates, these same men created violent coastal frontiers. On shore – whether on leave from a ship in port, working on a whaling station or scrambling across coastlines in the pursuit of seals – the peace they experienced at sea might shatter into a waterfall of cascading conflict.

Maritime employment offered a tenuous semblance of security in a violent world, outside the comprehension of contemporaries and beyond their prying eyes.

This article is Part 2 in a two part series exploring the role of Indigenous people in colonial maritime industries in eastern Australia and New Zealand.