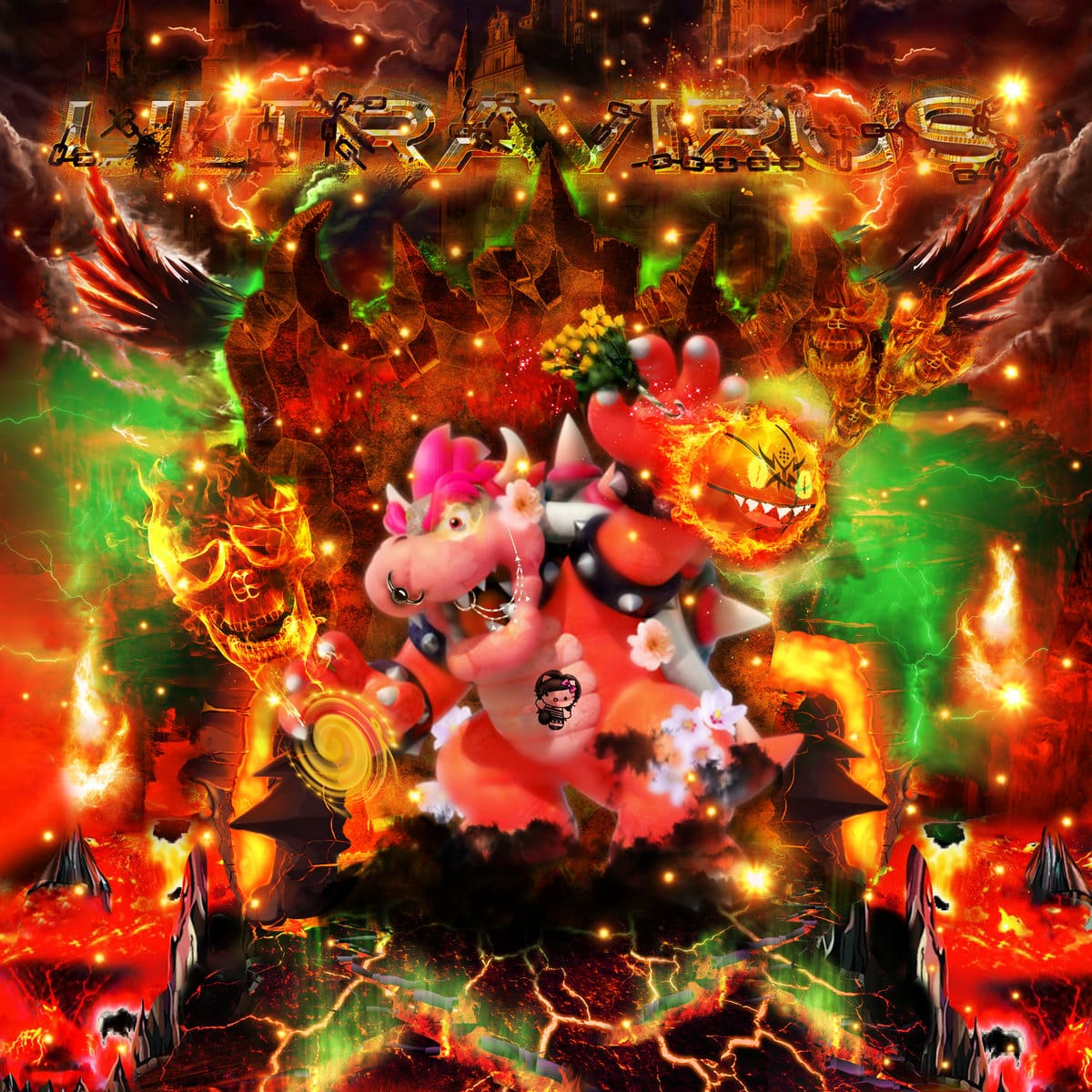

ULTRAVIRUS is a many-headed Hydra. Thorsten Hertog (aka Thick Owens), co-founder alongside Ella Parkes-Talbot, describes ULTRAVIRUS as “a content aggregator, net label, ongoing party series and fashion brand”. Another way of explaining ULTRAVIRUS is that it is a representation – or an exaggeration – of cybercultures. It feeds off soul-sucking consumerism, the vapid irony of contemporary youth culture, exemplified in meme culture, and the non-linear consumption of music and narratives in an internet era of information overload to present kitsch music aligned to our ravaged attention spans. Think hyperlink wormholes, internet-induced psychosis and cybermedieval avatars. If you’re a little disorientated and a little confused, you’re in the right place.

While not grounded in any one location, ULTRAVIRUS skirts the edges of Sydney’s DIY rave scene. “I started the net label last year because I felt like there weren’t labels in Australia representing the sounds I was really interested in – these kind of breakcore, gabber and hard tek sounds that I was hearing in warehouse spaces and that I saw a lot of bedroom producers making and uploading to Soundcloud… I think labels are hugely important in functioning as an incubator for ideas but also as a platform for a scene.”

This homage to Sydney’s warehouse and bunker rave scene is a sharp departure from outsider perceptions of the scene and a powerful statement addressed – albeit indirectly – to the global music hierarchy.

Thortsen fires off a whole barrel of pot shots when I interview him. The first target is streaming platforms. “The issue with Spotify is that there is an economic imperative to keep people listening as long as possible to boost advertising revenue. That has bred a culture of music that is very playlistable – you know, the hang-out-at-home playlist or the Valentine’s-Day-romance playlist.”

New York Times journalist Jon Caramanica has disparagingly labelled this sound, with both pop and EDM variants, “Spotify-core”. Defined by emo lyrics, slow, chill beats, hip-hop influenced production and an early drop and chorus to satiate ever-shortening concentration spans – think Spotify-sponsored artists like Drake, Billie Eilish, Charlotte Lawrence and R3hab – this music is specifically made to be innocuous, little more than background music.

You don’t need to pay a membership fee to listen to ULTRAVIRUS releases. They are not available on Spotify. Both ULTRAVIRUS releases – a five track EP, ༒•fetid in wingdings•༒, and a ten track album, Plunderzone™, released last month – use a name-your-price model on Bandcamp. ULTRAVIRUS also uses a Creative Commons Licence “so people can take the music and remix it and use it in their own art without having to pay royalties to the label or the artist. That’s honouring the early philosophy of net labels and the internet.”

“I was really inspired by early 2000s net labels, which came out of this early utopian idea of the internet being a democratic and commercial-free zone. Obviously we know that that idea of the internet has failed. But people just downloaded and uploaded music in bulk for free. The artworks were super tacky and it was very DIY.”

Second in the firing line is the type of music Thorsten sees over-represented at clubs and some warehouse parties. Like the album artworks – chaotic collages of colour and competing images – the music ULTRAVIRUS platforms is “intentionally offensive and abrasive”. Almost all tracks are fast and jarring. There is breakcore, NeuroTrap, noise, deconstucted club, memecore and more. Tracks like Bouti’s DJ Snake and SPLITROACH/TERRORSLIDE/2049-2NX’s HAKKEN PHOENIX go anywhere and everywhere, leaving themes, coherence and genre classification strewn by the wayside like a yardsale. So nothing like Spotify-core then.

A bunch of Sydney producers provide the mesh for this enclosure of unhinged, avant-garde madness, reflecting the myriad ways in which alternative clubbing spaces encourage and breed innovation. Thrax, crack_lips, DJ BEVERLEY HILL$ and duo SPLITROACH/TERRORSLIDE/2049-2NX are all hidden gems of the warehouse scene.

As a founder of group projects including Okra, Haus of the Rising Sün, Soft Centre and ULTRAVIRUS, which have utilised warehouses and reclaimed spaces, Thorsten’s imprint on the music of Sydney’s underground is significant.

Sitting in front of the camera, in front of a future audience – I am interviewing Thorsten as part of a documentary on Sydney’s DIY rave scene – Thorsten appears comfortable. He is ambitious yet grounded, and extremely well-spoken. He cares. You sense that he really means every word he says. This capacity to talk with conviction without speaking loudly has undoubtedly helped people buy into what he envisions. But he has not done it all alone.

In the last two years, a new wave of party curators have emerged in Sydney and laid down a bridge between experimental electronic sounds and hard dance, perhaps none more successfully than the team behind Soft Centre.

Thorsten, alongside a network of like-minded artists and event organisers, has helped transplant the ethos of warehouse raves into a new, legal home – the Casula Powerhouse Arts Centre – for the experimental music and art festival Soft Centre. With support from Liverpool City Council and funding from Create NSW, Soft Centre is a far more legal adventure.

Boundary-pushing, Soft Centre puts local artists, sometimes with only a few performances under their belts, on a stage alongside international headliners, often at peak times. With over 1000 attendees, there is a sense that Sydneysiders’ appetite for challenging music is deep.

Resident Advisor’s (RA) recent documentary on Sydney’s underground scene, meanwhile, suggested that ambient and house music distinguish the Sydney scene. According to the documentary’s logic, Australia’s beautiful natural landscapes and beaches encourage music production centred on tranquillity and relaxation.

Insightful and optimistic, but limited in scope, the RA documentary Real Scenes: Sydney shows just how easy it is for outsiders to misinterpret alternative clubbing cultures. To a vast cross-section of Sydney ravers, house and ambient do not represent the totality of the DIY rave scene. If Sydney has a distinctive sound, it is diversity, and ULTRAVIRUS is a testament.

Thorsten describes the resurgence of hard dance and the burgeoning IDM and glitch scenes, while still niche, as “a retaliation and protest against the huge saturation of nu-disco and house sounds and vanilla-boom-clap club music that dominates Australia.”

Sydney’s hard dance revival is also due to “our proximity to Newcastle and the Bloody Fist [Records] scene that existed there in the 90s, and the huge breakcore scene that exists in the Blue Mountains. These two cities pioneered these hard dance sounds. That has totally filtered back into Sydney.”

Sydney and its satellite cities have produced a long line of DJs and producers unafraid to mock the nation’s cultural cringe with their confronting styles of hard dance music. In 1994 in Newcastle (Australia), Mark Newlands founded the label Bloody Fist Records with two fortnightly dole payments. Cornered by smoke stacks, barbed wire, steelworks operations and concrete, the label became a production line of its own for a pinball machine of eclectic hardcore beats. The music was nihilistic and cynical. Records such as Straight Outta Compton were ripped off, rejigged and regurgitated with a blatant disregard for copyright laws (in this case as the thoroughly distasteful EP Straight Outta Newcastle). This DIY, cut and paste mentality shaped the production of Australian breakcore artists such as Passenger of Shit, Melt Unit, Toecutter and Noistruct.

Australia has exported numerous house DJs, yes, but will these artists leave a legacy in an oversaturated market? Possibly. But if Australia has truly produced any distinctive sounds in dance music, it is the sheer lunacy of extreme, left-field artists such as Nansenbluten, Passenger of Shit and Anklepants. With their provocative, almost anti-intellectual, music, we seem to struggle to take pride in them. This perhaps helps explain why pioneering Australian hardcore artists including Geoff Da Chef (Blown Records) and Hedonist (Bloody Fist Records) still DJ and tour in Europe but fly under the radar at home. Industrial connoisseur Tymon cut his teeth in the Sydney rave scene in the late 90s before migrating to Berlin and releasing music through iconic labels such as Industrial Strength Records. He too rarely rates a mention as a cultural export.

ULTRAVIRUS is therefore a continuation of what was already there. As Thorsten says: “There is a perception that the warehouse scene post-lockout was ground zero for Sydney dance music. But what people forget is that there was a huge scene that existed before all that happened.”

It is precisely Thorsten’s style of DJing, which he labels as “irreverent and rude”, which encapsulates, if not Australia’s natural landscapes, the zeitgeist of a young nation forever unsure of itself. Self-mockery, tongue-in-cheek probes at authorities, unapologetic nods to Australia’s cultural cringe, larrikinism and a tinge of political commentary pulsate throughout local techno, hardcore and breakcore. DJs like Thick Owens bounce seemingly carelessly between silliness and serious critique.

In September 2018 at the warehouse rave Grip: Interstellar Funk, Thorsten (as Thick Owens) began his set with a breakcore Metallica riff, dressing the discordant sounds in a patchwork shirt of news reports about pill-testing. “I never want to see this event held in Sydney or New South Wales again. We will do everything we can to shut this down”, says NSW Premier Gladys Berijiklian, just before Thorsten throws down a thumping, pitched-down Frenchcore kick by FKY.

* * *

ULTRAVIRUS is an eclectic entity and it is possible to go back even further in time than Thorsten does when searching for influences. The techno-hardcore spectrum has deeper roots in punk than quite possibly any other musical scene.

Hardcore punk was a volatile critique of the stardom of 70s rock’n’roll, defined by dissonant melodies, shouted vocals, disruption, excess, irony, disdain for public and private property and outsider status in a capitalist system. In the face of commodification, political activism and direct action became essential for authenticity and ownership over the “punk” label.

Dance music culture celebrates collectivism and, like punk, disintegrates the passive spectator/genius performer dichotomy embedded in rock. Long associated with direct action via ‘protestivals’, raves are inclusive, democratic and participatory. By bringing together musicians, performance artists, visual artists and lighting specialists, raves create a multi-sensory overload designed to stimulate in attendees altered forms of consciousness and new, healing ways of being.

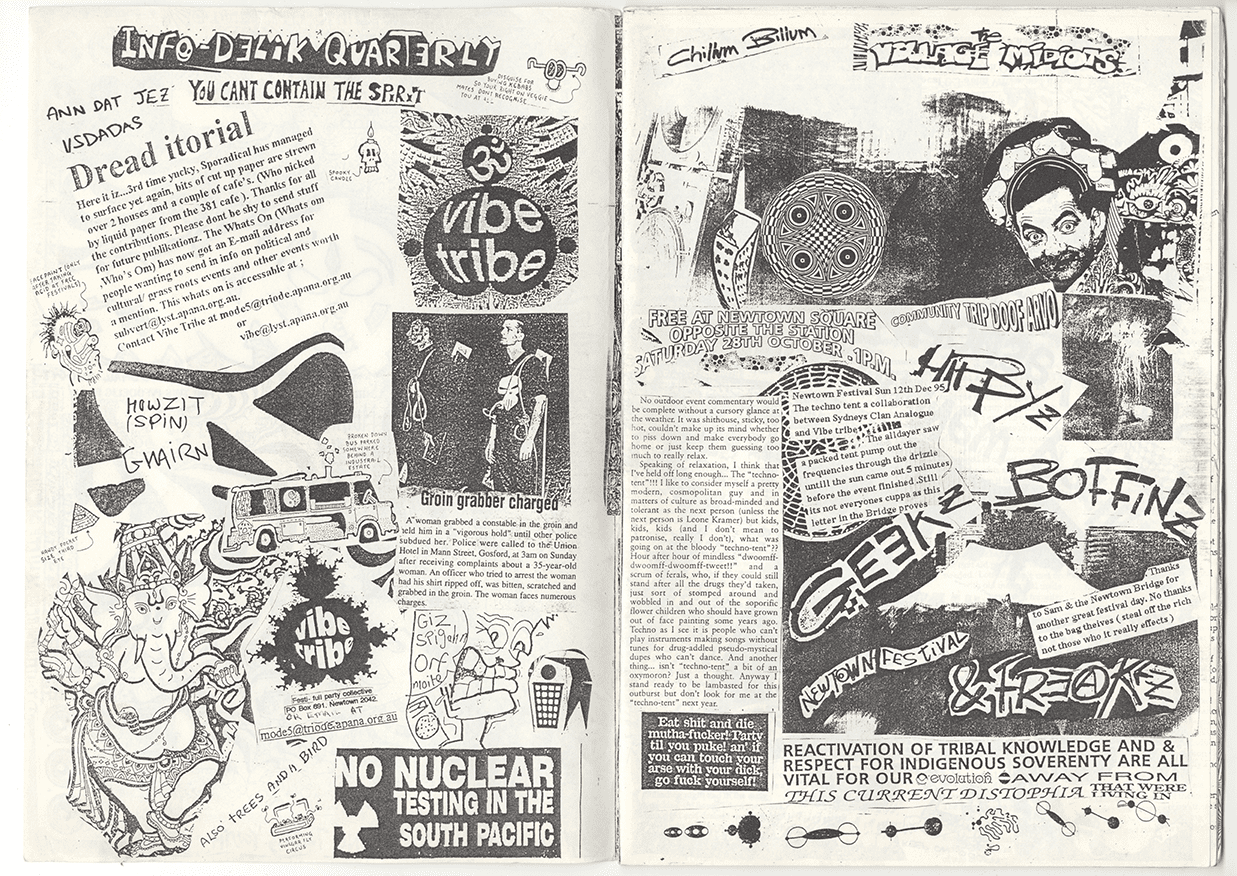

Recognising a particular contiguity between the harder ends of the punk and techno spectrums, Graham St John, a cultural anthropologist now at the University of Fribourg, has traced the continuation of anarcho-punk politics in Sydney with the emergence of what he labels “techno terra-ists” in the early 90s.

As the 80s waned and the 90s took over, there was a sharing of equipment and personnel between the anarcho-punk scene, centred around Newtown and Redfern, and early techno artists and collectives such as Non Bossy Posse (NBP) and Vibe Tribe. At the communally-owned Jellyheads venue near Central Station, punk bands, DJs and live electronic acts shared the stage until electronic music stole the limelight altogether and Vibe Tribe was born. Around the same time, Bloody Fist Records emerged, which was a lot less political. But the label shared the same anti-authoritarian, anti-commercial ethos.

At warehouse parties and Vibe Tribe doofs, NBP sampled advertisements and radio segments. Tossing commentary on Indigenous land rights, social justice and environmental sustainability into a headwind of preprogrammed techno and trance beats, NBP pinpointed the dancefloor as the target of their sonic, political cyclone. According to Kol Dimond, a member of the anarcho-pop punk band the Fred Nihilists and later NBP, this was live “finger looped mayhem”. Besides the lofi psychedelics emanating from the chill zones at Vibe Tribe parties, the music was “very techno and very acid… generally anywhere between 140 and 160 bpm.” NBP represented the “same politics, same passion for systemic social change, just a different soundtrack.”

When 40 riot police turned up at the Vibe Tribe party Free-quency in Sydney Park in April 1995 due to noise complaints, the crowd – anywhere between 500 and 2000, depending on who you ask – repelled the police. With organisers rallying the crowd over the mic, they formed a circle around the speakers and decks, preventing the police, initially anyway, from cutting off the music. This was not a case of intoxicated revellers misbehaving. Kol asserts that it was a coordinated effort in an already highly politicised space – just one of many plans inscribed in the Vibe Tribe manifesto to “deal with skinheads or thugs or coppers.” Non-violent resistance was the goal but scuffles broke out. According to one account, police “couldn’t deal with the concept of ‘everyone being in charge’”.

At 2am, having regrouped, police charged the dancefloor in a wedge formation with batons, shields and dogs and carried off the generator. Two punters were hospitalised, countless injured. The crowd remained in defiant assertion of their civil rights and a mob of bongo drummers turned up to make more ruckus.

If there is a vague ideology behind rave organisation, it hovers closer to anarchism than a neo-conservative appreciation of small government. As football hooligans and bomber-jacket wearing skinheads with fascist and misogynistic inklings populated gabber, and techno became less revolutionary, in the early 2000s breakcore – then in a darker form than the cartoonish popmash-breakcore that dominates today – became a haven for decibel-addled ferals with alternative lifestyles and a masochistic passion for fast, abrasive sounds. It became synonymous, albeit briefly, with anarchist politics. Some claim it was a direct response to Neo-Nazism (see the documentary Notes on Breakcore). In Sydney, the collective and record label System Corrupt, containing within its ranks ex-Bloody Fist artists and ex-Vibe Tribe members, threw free raves in abandoned places. Shockingly subversive, event promotion included pornographic collages.

Spaces marginal to the functioning of society – wartime bunkers, abandoned buildings, disused warehouses, motorway underpasses and marshland – became stages for niche communities who otherwise struggled to find venue owners willing to take financial risks. Opening in 2008, the Sydney warehouse Dirty Shirlows, for instance, hosted cheaply-ticketed punk and breakcore gigs, regularly blasting experimental noises into the early hours of the morning, until police pressure and fines from Marrickville Council forced its (official) closure in 2012. The utilisation of alternative “venues” – a legal grey space – is unique to both punk and rave culture.

Murray Bookchin in his polemical essay Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism: An Unbridgeable Chasm argued that Hakim Bey’s concept of a “TAZ” – temporary autonomous zone – and temporary ferality exemplifies the “lifestyle anarchism”, “social indifference”, “egotism” and disinterest in revolution of young, urban professionals. While the “TAZ” has become a byword for the Freetekno movement, Bookchin suggests “a TAZ is a passing event, a momentary orgasm, a fleeting expression of the ‘will to power’ that is, in fact, conspicuously powerless in its capacity to leave any imprint on the individual’s personality, subjectivity, and even self-formation, still less on shaping events and reality.”

Unlike Bookchin, I believe that certain raves (“TAZs”) at an abstract level encourage alternative ways of living and provoke critique of dominant systems and constructs. Prior to the COVID-19 lockdown, Sydney’s underground rave scene certainly seemed on the precipice of commercialisation. With warehouse tickets costing between $20 and $60, occasionally even more, questions must be asked about the durability of anarcho-punk politics.

High ticket prices can translate into a night of drug-fuelled revelry, connection and muddy shoes before the crowd returns to reality, re-energised and ready to ascend the corporate ladder. As public acceptance of dance music grows, increased prices of entry has seen digestible, non-confronting music – tech-house and disco, for example – enter the warehouse. Hardly the soundtrack of protest.

The punk and rave scenes tend not to overlap in Sydney in the ways that they did in the early 90s, however, some recent events by Soft Centre, Hex Yellow and KEIU have seen a cross-over of punk bands and hard techno, and punk’s DIY attitude remains as strong as ever within the rave community.

The story of punk and metal musicians transitioning from guitars and drum kits to drum machines, decks and mixers is startlingly common. But rave did not replace punk with the proliferation of acid house parties from the late 80s, as some like to believe. In recent years Sydney labels Burning Rose Records and Deep Seeded Records have championed hard techno alongside punk, darkwave and industrial projects, fostering tracks that mix anti-establishment lyrics and thrashing electric guitars with techno beats.

The RA documentary Real Scenes: Sydney sparked furious debate about what represents Sydney’s rave scene. By focusing on house and ambient, the film bypassed 30 years of history. Sydney, and New South Wales more broadly, has long been a hub for extreme music and radical politics. Thorsten claims Sydney is “the capital of hard dance” in Australia.

ULTRAVIRUS could be viewed as a jaded postmodernist sigh – utterly obtuse and irrelevant – rather than an anarcho-punk battlecry. Indeed, ULTRAVIRUS probably won’t change the world. But its emergence not just as a one-off event, a TAZ, but as a net label is an attempt, consciously or not, to solidify a punk legacy. The ways in which ULTRAVIRUS nostalgically harkens back to optimistic visions of the internet as a decentralised, democratic space cannot be ignored. The label’s hybrid, “edutainment” events, which incorporate panel discussions and art within raves, suggest that founders Ella Parkes-Talbot and Thorsten Hertog have something more profound in mind than dancing blindly into a capitalist apocalypse.

Reflecting the evolution of dance music technologies and rave culture, ULTRAVIRUS looks to the future while drawing on the past for solutions. In the face of mega corporations including Spotify and RA, Ultravirus is a bold reclamation of identity for Sydney’s underground but one that is true to its roots.