Two days after Donald Trump refused to condemn white supremacists at the first US Presidential debate, I rang New York-based Jewish cartoonist Eli Valley. Joining the call in the midst of uploading his latest piece to Twitter, he apologised, though stressed the importance of a well-timed tweet given the frenetic political climate, noting it was likely he’d soon be compelled by new events to produce another cartoon. Of course, he was right. About five hours after our call ended, social media feeds and group chats erupted in schadenfreude-induced frenzy as news broke that the President had tested positive for coronavirus. Valley predictably picked up his pen once again.

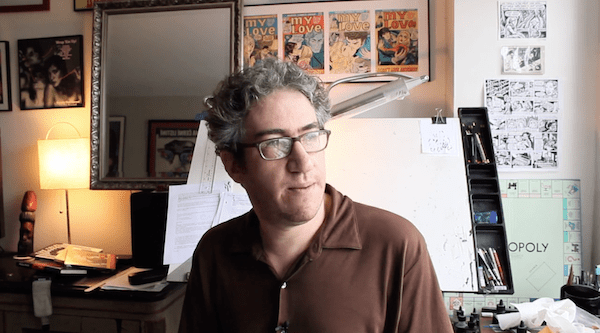

Known for his distinct heavy black and white caricature style, acerbic wit and attracting the ire of the political, media and Jewish establishments alike, Valley has emerged as an iconic figure within the American left, with a particular following amongst a revived Jewish section.

Raised in upstate New York and New Jersey, Valley’s parents — a conservative rabbi and rebbetzin (rabbi’s wife) — divorced when he was six years old. In leaving her husband, his mother also left religious orthodoxy behind, shaping Valley’s adolescence as one marked by pronounced political differences. She became a social worker and dated an incarcerated African American man that she counseled, whilst his father delivered Shabbat services at synagogue, lecturing on the dangers of intermarriage. Moving between an “intense Jewish communal environment” and a “secular environment” “informed [his] approach both to Judaism and to wider politics” growing up.

He describes his upbringing as “Zionist in the formal and informal educational spheres. So pervasive, like the water that you drink and the air that you breathe. I must have been a Zionist myself without even realising or naming it as such.” His answer is strikingly familiar. Whilst growing up in a liberal, secular household myself made it easier to recognise and interrogate this atmosphere, I attended a modern orthodox Jewish school for three years where Zionism was ubiquitous. From Jewish Studies classes, singing Hatikvah (the Israeli national anthem) at school assemblies or the several kids who inevitably wore IDF shirts on mufti days. Why any twelve year old would choose to wear an ugly khaki shade over, I don’t know, JayJays or Supré, was beyond me!

It was during these same school years where Valley was experiencing Israel as “the bedrock of the American Jewish community,” that he discovered MAD: a comic magazine he cites as his greatest artistic inspiration. To Valley, MAD was Jewish authenticity. “There was this cacophonous Jewish sensibility flowing through their pages and panels.” MAD also “satirised so many truths and assumptions of American political and cultural life — McCarthyism, consumerism, commercialisation in the post-war period, racism — and they were coming at it from a no holds barred perspective which was invigorating. There was a total renegade artistic and narrative style.”

After graduating from high school, Valley studied English at Cornell and drew cartoons for the student newspaper, The Cornell Daily Sun, where figures such as E.B. White (Charlotte’s Web) and Kurt Vonnegut (Slaughterhouse Five) also cut their teeth. However, churning cartoons out twice a week came to be a “gruelling work schedule” alongside studying where a “a lot of [his] work was forced illustration of the news. One of the things I like about what I’m doing now is I don’t force them, I do them when I’m compelled.”

Unable to find work in America and hearing of possible employment opportunities abroad, Valley moved to Prague in the 90s, portfolio in hand. Whilst he never got a job at one of the two English newspapers in the city, a combination of loneliness and basic Hebrew led him to becoming a Jewish tour guide. “Making some generalisations,” Valley describes the Israeli tourists as “acting like they know everything,” yet he found giving tours to diaspora Jews particularly enjoyable. “Their lens of Jewish history, particularly within Europe was confined to a graveyard approach, largely because of their Zionist upbringing and pedagogical background…To be able to impart not just the cemetery history, but also the vibrant Jewish culture…that was really gratifying.”

Rising antisemitism in the places Valley used to give tours has him feeling horrified, particularly given Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s willingness to forge alliances with such figures like Viktor Orban. “Israel has made its choice to solidify ties with far right leaders who are antisemitic, but it turns out the values of antisemitic authoritarians mesh pretty well with the values of Israel’s political leadership,” Valley says bluntly.

Whilst living in Europe, Valley published his first book in 1999: a travel guide of Prague, Warsaw, Krakow and Budapest, which featured a blurb from Nobel Peace Prize winner and Holocaust survivor, Eli Wiesel who described it as “beautiful and melancholy…” Fifteen years later, Valley would go on to produce “Wiesel, Weaponized”, a comic for the left-wing +972 publication satirising Wiesel’s propagandistic support for the Israeli assault on Gaza in 2014. The cartoon shows Israeli scientists attaching both Wiesel’s head and brain to a drone used in Gaza as they shout phrases like, “This is a battle between those who celebrate life and those who champion death!”

Realising he would have more success with his creative pursuits in America, he returned soon after the book was published and wrote op-eds during the Bush administration on topics such as the Iraq War. Admitting he was “falsely under the impression that everybody could write, but not everybody could draw,” combined with his love for MAD and the “exhilaration for translating political ferocity into visual media,” he found his way back to comics. This included entering an Israeli cartoon competition mocking an Iranian newspaper’s callout for Holocaust cartoons. Whilst Valley didn’t win, inspired, he began cartooning professionally, freelancing for various publications and eventually becoming the artist-in-residence at the Jewish publication, the Forward.

He described his experience at the outlet as “a constant struggle to be able to get things into print,” clarifying that whilst his personal editors enjoyed much of his work, the editor-in-chief at the time “approached comics the same way she approached journalism, which is that you should show both sides of an issue.” This approach didn’t make much sense to Valley, an artist firmly of the view that satirists aren’t there to illustrate both sides, but to produce polemic work. “There’s no need to get quotes from people you’re mocking, right?”

Tensions at the publication reached a boiling point towards the end of 2013 when the Forward published “It Happened on Halloween”, which saw Valley draw then-head of the Anti-Defamation League (an international Jewish NGO), Abraham Foxman, attacking Jewish people for not being conservative enough. Foxman was livid and boycotted (“funny for a man who doesn’t like boycotts”) the publication.

His time at the Forward was up, but it didn’t amount to “an immediate break, that would have been a news story in itself,” but a “distancing process” where he would no longer be published there. “It was a divorce.” Pertinently, Valley’s experience is indicative of a larger trend within the Jewish Anglosphere, where an officiated Jewish leadership (more right wing and religious than the majority of the Jewish community) seek to frame themselves as at best, the arbiters of, and at worst, the police of Jewish authenticity, legitimacy and even humour.

Valley’s book of comics, Diaspora Boy, published in 2017 revels in celebrating a secular, universalist and social justice oriented vision of Judaism. Subversive and filled with dark humour, Peter Beinart is correct in saying the book “constitute[s] a searing indictment of the moral corruption of organized American Jewish life in our age.”

However, intense criticism, such as being called a self-hating Jew and a Kapo (a Jewish person who helped Nazis), no longer phases Valley. “The whole idea of self-hatred presupposes that our ‘self’ is Zionist and often times orthodox,” he explains. “It’s important to not allow them to define us given the moral squalor of so much of the Jewish right in the era of Trump and Netanyahu.”

Today, Valley sees reality as “continually eclipsing satire, not only in absurdity but in profanity.” Yet, unlike more liberal or centrist satirists, Valley resists making fun of Trump’s “clownishness” and the “more superficial aspects of the Trump administration”, choosing instead to highlight the “pernicious, venal policies that he and the Republican Party are pursuing.” “I feel like I’m drawing reality, it’s one of the reasons I often use real quotes. I’m drawing the nightmare as it is.”

Speaking to Trump’s endorsement of the Proud Boys in invoking their “stand back, stand by” phrase, Valley stresses that “the big uproar” from the commentariat should not be limited to these public, soundbyte displays of white supremacy, as with what happened at the debate or his remarks about Charlottesville. “This administration has been implementing ethnic cleansing policies from the start,” he says. “Stephen Miller who has the most extreme white supremacist proclivities…that’s the guy who’s been writing border and immigration policy.”

Ultimately, Valley is unconcerned with attempting to convince people with his cartoons. Instead, he sees his comics as playing a small part in trying to “remind people on the Left that we’re not insane, to galvanise us politically during a time of rising authoritarianism.”

“The left is besieged and attacked. This is about punching back.”