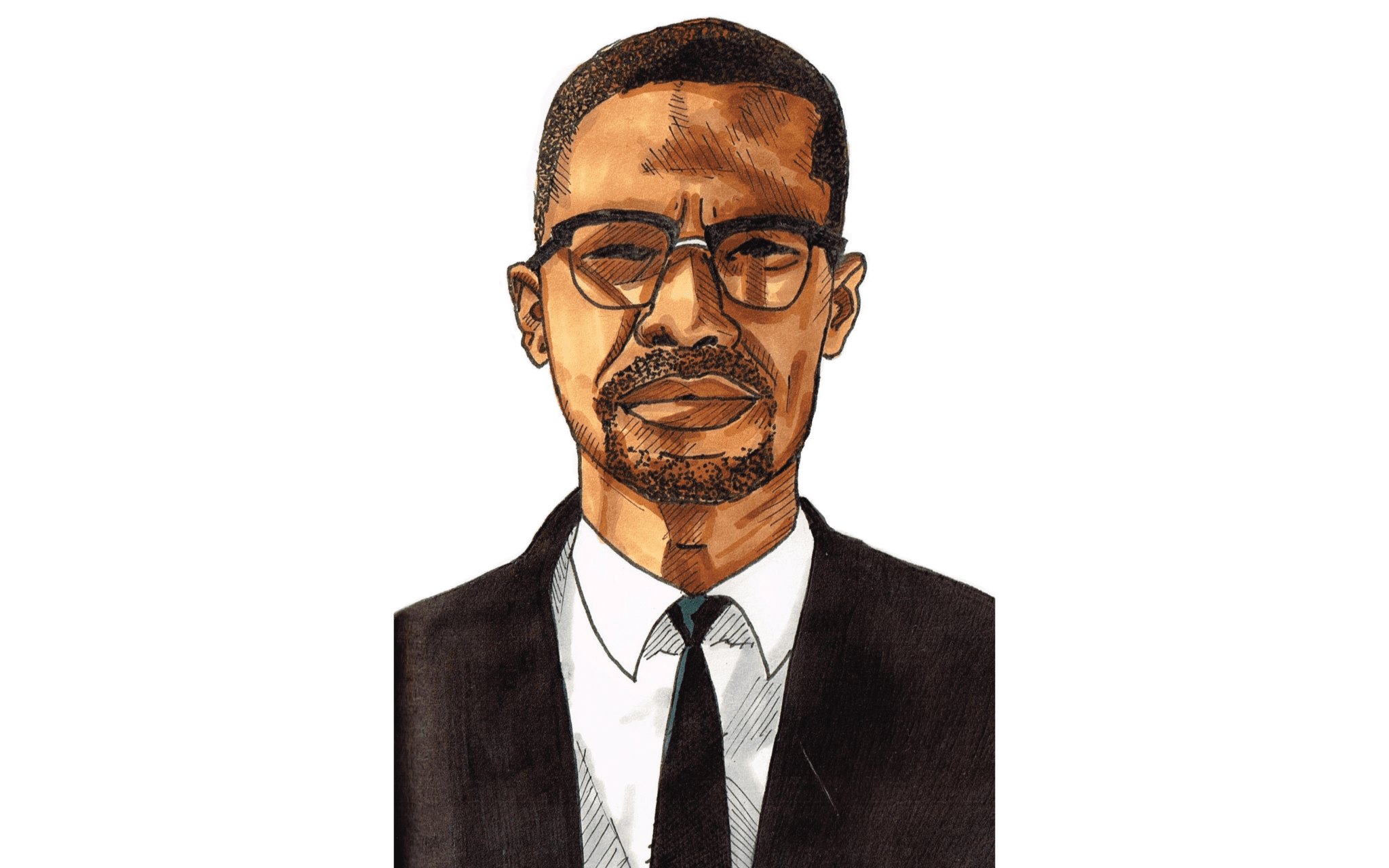

February 21, 1965. 21 gunshots brought about the death of a man whose name would receive every reaction conceivable. It was the end of the story of a fierce advocate of agency, power and civil rights, nothing short of mythical: Malcolm X.

Malcolm X, whose Muslim name is el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz, was a martyr. He had become a shaheed — one of the highest honours a Muslim can ever possess. While his rise with the authoritarian Nation of Islam became his ironic downfall, he knew very well the death that awaited him, which added an almost prophetic quality to his epic, heroic tale.

His experiences mirrored his community’s movement from rural peasantry, to industrial proletariat, to post-industrial redundancy. Allied to this is his spiritual redemption and movement away from nihilism. Factor in his yearning for knowledge, how can one not be inspired by the Malcolm who educated himself in the midst of a jail sentence?

He moved away from the dogmatic, exclusionary Nation of Islam to the pluralistic, inclusive Sunni Islam which transcended racial and cultural creed. Much like the literary and Abrahamic prophets of old, there was a struggle, a calling to faith and the building of a world built on the tenants of radical liberation. We have much to learn from an almost messianic tale that embodied activism, redemption, and love.

Indeed, prophetic and messianic are immense forms of praise. Followers and admirers of Malcolm X understand this. So did his enemies. In a memo to the offices of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, former Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, stressed the need to nullify Malcolm X’s influence to prevent the rise of a ‘”Messiah” who could unify, and electrify, the militant black nationalist movement.” Hoover also enunciated a final goal of preventing the growth of militant organisations and rhetoric amongst young people.

But these were forlorn plans. The prophetic model of Malcolm, so beautifully detailed in Malcolm’s and Alex Haley’s The Autobiography of Malcolm X, inspired thousands of young adults: Afro nationalists, Communists, Marxists, Muslims. Decades later, his work has become part of the canon of many university courses.

Both Muslim and non-Muslim youth, with a sharp criticality and sophistication, became readers of Malcolm’s philosophies. I am the former, a young Muslim, struggling with his identity and the capacity to find Muslim heroes who changed the world as I knew it — a Western world plagued by racism, the ravaging devastation of colonialism and a painful shortage of agency.

As a Levantine Arab, I cannot entirely, and without some degree of friction, claim the Malcolm who reinvigorated the resistance of African American communities as my own. I can only respect, admire, learn, and express my utmost solidarity and support for such a struggle. However, I can genuinely claim Malcolm the Muslim, el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz, who I believe can be of much guidance to those to those with a deep commitment to societal and personal transformation.

After his trips to the Islamic worlds of Africa and the Middle East, el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz linked African American liberation to global liberation of those who suffered the brunt of US imperialism. This was a Malcolm who began to vehemently oppose the global machinations of American power and propaganda that had subjugated not only Africans but Arabs. Malcolm had begun to dedicate himself to the umma, the collective body of all believers united in faith and inseparable by any material means.

As a Muslim of Palestinian heritage, to me Malcolm X had not only become a hero I could only admire and respect from afar, but a hero I could call my own as he criticised Israeli injustices against my own people. Malcolm had stressed the necessity of claiming justice for all; that justice for some would not be a cause worth pursuing. As poverty, racism, sexism, colonialism and war continue to plague the world we find ourselves in, we would do well to follow Malcolm’s model: recognise the universality of a struggle, tied in with all causes against that which is inhibitive, repulsive and shameful.

Redemption should be at the core of such a struggle, which is the very thing that Malcolm exemplified. His conversion from crime, hatred and nihilism to that of the Islamic faith, and his reconsideration of his own racial illusions regarding ‘whiteness’ is mythical. Malcolm was willing to question his once held convictions. After his iconic pilgrimage to Hajj, he wrote:

There are Muslims of all colours and ranks here in Mecca from all parts of this earth. During the past seven days of this holy pilgrimage, while undergoing the rituals of the hajj [pilgrimage], I have eaten from the same plate, drank from the same glass, slept on the same bed or rug, while praying to the same God—not only with some of this earth’s most powerful kings, cabinet members, potentates and other forms of political and religious rulers —but also with fellow‐Muslims whose skin was the whitest of white, whose eyes were the bluest of blue, and whose hair was the blondest of blond—yet it was the first time in my life that I didn’t see them as ‘white’ men. I could look into their faces and see that these didn’t regard themselves as ‘white.’

This redemptive open-mindedness was further shown in Malcolm’s discussion of Islam with Tariq Ali at Oxford University. As Ali rebuked faith with a scorn, Malcolm listened respectfully and attentively and replied, “it’s good to hear you talk like that…I’m beginning to ask myself many of the same questions.”

There was a humility to Malcolm that accompanied his conviction in faith and political activism. This humility and redemption should be cause for hope: people are capable of change. Hatred would not be a weapon against injustice. Malcolm recognised that and began to engage with something more radical: love.

Cornel West affirmed that justice and love were inseparable. Malcolm’s faith; my faith; was one that affirmed that one cannot truly believe until we love others as we love ourselves. Malcolm took up that mantle of Islam and revolutionary love. One only has to consider and appreciate this prayer he once opined to understand:

“I pray that God will bless you in everything that you do. I pray that you will grow intellectually, so that you can understand the problems of the world and where you fit into, in that world picture. And I pray that all of the fear that has ever been in your heart will be taken out”.

Grow intellectually. Remove fear. That’s what Malcolm prayed for. Find a way to claim some part of his almost prophetic, Messianic tale as I have claimed him; while Malcolm died on February 21, 1965, his cause and ideals did not. Find a way to express and harness the radicality of activism, redemption, and love. The world needs that triune of progress that my Malcolm, the Muslim Malcolm, came to embody so well.