If you were a student at the University of Sydney in the 1980s, you wouldn’t have been able to find any academic support outside of your coursework, besides English classes for non-native speakers. Many students — native and non-native speakers alike — found it difficult to grasp the conventions of academic writing and learning.

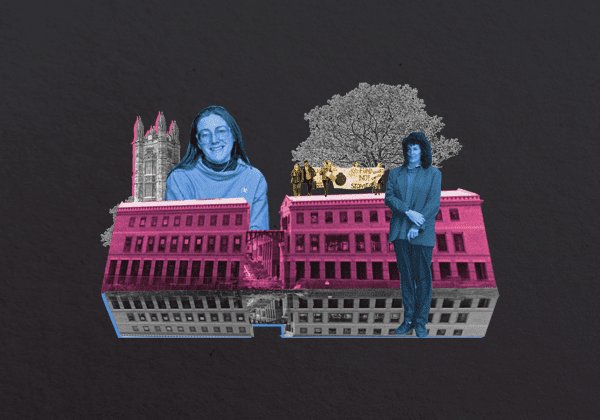

So in 1991, after an internal University review, a small team of linguists and educators, including Carolyn Webb, Suzanne Eggins, Janet Jones, Karen Scouller, Peter O’Carroll and Helen Drury, set out to change this, establishing the University of Sydney Learning Centre in the Old Geology Building.

“It was visionary at the time … [we recognised] that all students needed support as they moved from high school into university,” says Drury. For decades, the Centre provided crucial academic support to the University community and contributed invaluable research into academic writing.

But in its 30th year, the Learning Centre has officially shut its doors. University budget cuts brought it to a subdued end, despite over 900 people petitioning against its closure late last year, and 85.8% of respondents in USyd’s 2020 Student Life Survey agreeing that the Learning Centre was an important service for the student community. It’s difficult not to feel the void left by its loss — decades of work completely dedicated to students.

The Centre was renowned for its expansive collection of learning resources. Webb’s ‘Writing an Essay in the Humanities and Social Sciences,’ for example, illustrated the differences between descriptive, analytical and persuasive writing, while the ‘onion model’ pushed students to add ‘layers’ to their arguments until they reached critical positions. They catered to students from a wide range of faculties — for science and engineering students, the Centre offered step-by-step guidance in writing research papers and lab reports. All these resources were grounded in linguistic theory, particularly Michael Halliday’s work on functional grammar, and were borne out of extensive research.

“We had a huge range of workshops, around 80 or 90,” says Dorothy Economou, who worked at the centre for almost 10 years. “What we did was very special. Students would accumulate knowledge about how language works in a way that doesn’t happen in a lot of places.”

When Economou did research for an architectural writing workshop, she found that assignment questions and instructions were often incomprehensible for first year students. “Even in lectures, they just saw pictures of buildings,” she says. So she set out to find ways to develop communication skills within the curriculum — a project she never got to finish before being made redundant.

Thousands of students benefited from one-on-one guidance from staff who were always willing to lend a hand, whether on sentence structure, essay writing, literature reviews or reading strategies. At times, students trusted the Centre’s empathetic staff with more personal matters. “Just having that one-on-one relationship with those students, in this very huge and impersonal university, can be very life-changing,” Drury says.

Many postgraduate and research students sought the Centre’s help too, as they had never been taught academic writing. Helen Georgiou, who completed a PhD in Physics back in 2014, remembers being stumped with writing an abstract for one of her assessments. “You’re thrown into this completely new environment where there’s a completely different form of literacy,” she said. “But my experience at the Learning Centre completely changed the way that I thought about language. I drew from it not only during my PhD, but in my current educational research and teaching.”

Behind the scenes, the Learning Centre did critical work with faculties and schools to improve teaching practices. If several students struggled with an assessment, they would take this to unit coordinators and would together brainstorm ways to make assessment requirements more accessible. They developed methods for staff to measure students’ literacy levels, for example, through non-assessable writing tasks in Week 1, so appropriate and targeted support could be provided. “We were always aware that it was important to collaborate with faculty staff, and to try to embed into the faculty curriculum the support resources that students need,” Drury said.

Much of this work and expertise will cease with the closure of the Learning Centre. While the University has set up a Learning Hub in its place, they have halved the number of staff. The new Hub will rely more on peer-to-peer programs and online resources, but Drury is sceptical, considering the University has only placed one academic staff on the team. “It seems to be a cheaper way of providing some of the support that units like ours provided.”

“There’s a belief that students who are struggling to write properly will eventually learn by osmosis or trial and error; or that the most important thing is the content,” Drury says. “But I think that the expertise of someone with a linguistics background, and insight into how language actually works, can’t be replaced.”

While the Learning Centre has left an important legacy that will live on in our essays, research reports and dissertations, the loss of its dedicated and passionate staff will certainly be felt across generations of students.