In May this year, the bloodied and beaten body of law student Thabani Nkonmye was found by his family obscured under bushes in a roadside ditch. Days earlier, his family had reported him missing to the Sigodvweni police, who denied any knowledge of his whereabouts and launched a public appeal. It later emerged that Thabani’s car, with a bullet hole in the rear bumper, had been sitting in the parking lot of the police station when his disappearance was reported. When asked to identify his body, Thabani’s mother found he “did not have eyes, had a hole on his right shoulder, thigh and next to the stomach.”

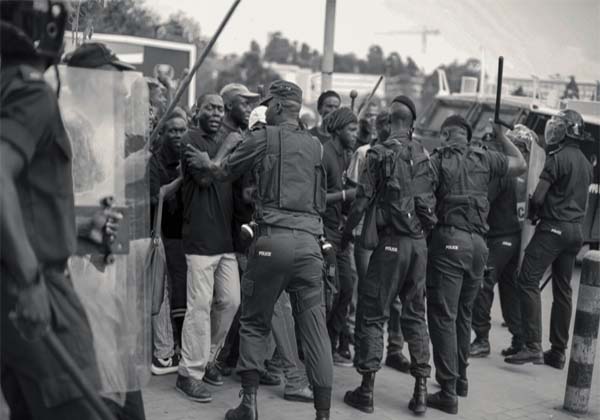

When the family returned to inspect his car for a second time, the bullet hole had been “tampered with and partially closed.” As suspicion of police involvement grew, student activists began to protest. Concerns over police violence, state repression, worsening economic conditions and the largesse of the royal family have seen the #JusticeforThabani protests grow into the greatest challenge to the rule of eSwatini’s absolute monarchy since the country’s independence.

Student activists have long been at the forefront of eSwatini’s pro-democracy movement. Honi Soit spoke to three current and former members of the Swaziland National Union of Students (SNUS) who have faced expulsion from university, imprisonment, terror charges and torture, to understand the nature and difficulties of organising a student union in a country where political parties are banned and unions are heavily restricted.

Absolute monarchy

Since ascending to the throne in 1986 at the age of 18, King Mswati III has presided over worsening economic conditions, continued to suppress opposition and deny civil liberties, while enriching himself and the royal family.

All political parties have been banned in the country since Mswati’s father, King Sobhuza II, abrogated the post-colonial constitution in 1973. While unions are theoretically permitted, they face great difficulty in obtaining legal status. The King has the power to appoint the Prime Minister, and approves all candidates before they are elected to Parliament. The King is the sole beneficiary of the national trust fund, which has grown into a billion-dollar vehicle for maintaining the royal family’s lavish lifestyle, with controlling stakes in mining, media, and agricultural operations. Nepotism is rampant within the government. For example, Princess Sikhanyiso Dlamini, the eldest of King Mswati’s 30 children, a USyd communications graduate, and aspiring rapper, is the Minister for Communication.

Despite the wealth of the royal family, the economy has worsened. The GFC saw allowances and benefits slashed as the government struggled to pay public sector wages, despite King Mswati’s contemporaneous purchase of a $50m private jet. Drought and disease — eSwatini has the world’s highest rate of HIV prevalence, while COVID has hit the country hard — have further worsened conditions.

Activists fight for education

In 2011, the government cut student allowances by 60% to a meagre $400 AUD per year. Maxwell Dlamini, President of SNUS at the time, led protests against cuts to allowances and the education budget, and advocated for “accessibility of funding for students to pursue higher education.” In conversation with Honi, Dlamini said that some students had been forced to resort to prostitution and criminality to make ends meet after the cuts. Brian Sangweni, SNUS President from 2017-19, described underfunding leading to critical shortages in lecturers and learning materials. Students are taught by unqualified lecturers, while those studying in scientific and digital laboratories have been left without the necessary materials for those courses.

Political activism

While SNUS has consistently advocated for student rights and education, the main focus of the union continues to be supporting the nation’s pro-democracy movement and demanding social and political rights from the monarchy. Bafanabakhe Sacolo, the union’s current Secretary-General, says that SNUS has been “part and parcel of what is [presently] happening in the country.” After Thabani’s death, it was the students’ union that led the first protests against the government, which have since spread across the country. Sangweni describes a growth in political consciousness across eSwatini’s tertiary institutions: “we have seen a lot of development among students in private colleges…they are beginning to embrace the union…During my time, we only operated in public universities.”

SNUS advocates for multiparty democracy in eSwatini, and possesses no formal links with other opposition groups: “our only relationship with political parties are the demands for democratic government…we meet in the streets, but that does not mean that we’re in any way influenced by political organisations,” says Sangweni. Sacolo describes SNUS’ current ideological platform as being informed by “materialism and dialectics,” with the principles of democracy, anti-sexism and working-class leadership underpinning the organisation. Many SNUS members have gone on to become involved with the banned socialist party PUDEMO, the country’s largest opposition group.

Repression

Because of their prolific organising, union members face continual harassment by state and university authorities, with informal threats and unrestrained legislative power used to silence dissenting student voices.

SNUS is an illegal organisation in eSwatini, having been denied registration by the government. Maxwell Dlamini describes meetings being “brutalised and dispersed violently” by the police during his term. The union is “prohibited from running meetings within university premises,” and Sacolo tells Honi that “if ever we are found to have been conducting union meetings within university, you meet consequences such as disciplinary hearings and suspension.” Brian Sangweni describes threats and intimidation from university hierarchies: “if you are a member of SNUS you are likely to experience instances of victimisation by lecturers and the institution…the institution will ask around about members of the organisations, and they will go to new members to tell them that joining SNUS is a very dangerous thing, saying that you might not be able to find employment once you’ve finished your course.” Coupled with regular arrests and suspensions, threats of unemployment are especially powerful in a country where the majority of companies are either controlled by the royal trust fund, or have close links to the ruling family.

Furthermore, Sangweni reports instances of students being coerced by universities to “sign bonds…that say [the student] will not participate in any forthcoming strikes or protests.”

Beyond the universities, the state has sought to break up the union through arrest and draconian legislation. Student activists are often arrested and detained on spurious minor charges, while the Sedition and Suppression of Terrorism Acts have been used to silence vocal critics of the government.

Since the beginning of Bafanabakhe Sacolo’s term in November last year, at least 20 students have been arrested for their involvement in SNUS. In one instance, seven students were arrested after boycotting class to protest unpaid allowances. Sacolo himself is currently on bail, after being charged, alongside two other members, with vandalising a police station on the day of Thabani’s memorial service. That same service saw Thabani’s mother and sister hospitalised, after police broke up the gathering with tear gas and rubber bullets. Sacolo tells Honi that he was kilometres away from the relevant police station at the time of the alleged vandalism.

The extraordinary lengths to which the eSwatini government will go to suppress dissent can be seen in the experiences of Maxwell Dlamini.

Dlamini was first arrested in 2011 on the eve of a pro-democracy rally. He was charged with possession of explosives, and was held in prison for over 14 months without trial. He has previously described being tortured during interrogation: “I was tied to a bench with my face looking upwards and they suffocated me with a black plastic bag…They did that over and over again until I collapsed. They told me that they will kill me for causing trouble in the country.” The police alleged that a box containing detonators and explosives was found during a raid of the students’ dormitory rooms. No evidence of the box’s existence was ever presented in court, and the charges were eventually dropped.

In April 2013, as General Secretary of the Swaziland Youth Congress (the youth wing of PUDEMO) Dlamini was arrested and charged with sedition for organising a protest calling for sham elections to be boycotted. While out on bail, he was arrested again in 2014 alongside PUDEMO leader Mario Masuku, and charged under the Suppression of Terrorism Act for wearing PUDEMO paraphernalia and advocating for the overthrow of the monarchy at a May Day march. Despite a successful constitutional challenge to the validity of the sedition and terror laws, Dlamini remains on bail, eight years after the original sedition charge, as the government appeals the case. Dlamini told Honi of the effects of his extended legal limbo: “my scholarship was withdrawn, I was expelled, and I could no longer study at any other university in the country…I can’t continue with my studies because [the government] won’t let me leave the country. I can’t work because the biggest employer is the government…even civic groups, if they employ someone like me, then you start to lose favour from the government…And I’m facing 25 years in prison.”

The scope of eSwatini’s sedition and terror laws is comically large. Any person who does or attempts an act with a “seditious intention” faces up to 15 years imprisonment. Being “likely to support…persons who act or intend to act in a manner prejudicial to public order” can attract 20 years imprisonment for subversion. Human Rights Watch described the two Acts as “providing sweeping powers to the security services to halt pro-democracy meetings and protests and to curb any criticism of the government, however banal.” Last week, three MPs were charged under the Suppression of Terorrism Act for voicing support for pro-democracy protestors.

Hope for the future

Amid almost three months of protests, King Mswati has shown no signs of bending to demands for reform, describing protestors as “satanic” and shutting down the internet to disrupt opposition organising. Police violence continues apace, with reports of security forces using live ammunition to disperse protests. In early July, 27 were killed in one week.

Nevertheless, activists see shoots of hope. Dlamini tells Honi that “in the past, the question of democracy has been more of an urban issue, among those that went to university. What is different now, is that this includes the majority of people from the rural areas to the urban areas, and even Parliament itself. People’s eyes are open, they see that the monarchy is quite a problem, that they need to address their own government so that we can hold them accountable and improve our lives.”