Disclaimer: This piece is written as a constructive critique of the leftist spaces I am a part of and adjacent to. My examples draw mainly from my own political spaces, but these criticisms encapsulate all left-wing spaces on campus. I write this in the hopes of better experiences for Women’s Officers and women in the left after me. I also recognise that this article is unfortunately one of many, continuing an ongoing critique.

As proven in multiple high-profile cases in Federal and State Parliament this year, sexual violence and sexism are rife in politics. This is not limited to right-wing political organisations, as was shown in the Greens case in 2018. Nor is it limited to political parties. We need not look further than our very own campus to recognise that under the progressive veneer of left-wing activist organisations are structural issues of sexism, misogyny, gendered labour and abuse. There is not one such organisation on USyd’s campus that is free of this. Imperialist, sexist, racist and classist structures are replicated in spaces where we organise against them, and reconstitute themselves endlessly in individual interactions by default.

Misogyny runs perniciously throughout the campus left. One woman who has been isolated and socially expelled by such a culture, writes that misogyny in the left manifests as “everything from unequal distributions of labour to the full blown espousing of Incel ideological world views. It became clear that even multi-year membership within an ostensibly progressive faction on campus could fail to meaningfully circumvent a lifetime of learned sexism as well as classism, an inherent and tragic outcome of elite private boys school education.”

Leftist men of higher social capital have used such advantage to get away with everything from publicly belittling and casting doubt against female activists’ abilities, to sexual coercion preyed upon younger, less experienced women. Known rapists and abusers are routinely invited to parties and social events, their victims the ones left off the invite list while other members still invited remain silent and complicit. Anonymous contributors recount bystanders who follow abusers to parties to ‘keep an eye on them’, afraid of their behaviour towards women in private, all the while bolstering their character in public.

One reason why abusive behavior, including sexual violence, is ubiquitous amongst the campus left is the desperate desire of these groups to protect their external reputation. With groups jockeying for support in elections and factionally-driven campaigns alike, what emerges within the group is a culture of unaddressed conflict, ‘justified’ as to keep the faction united. Even more galling is the insinuation that the ‘negative peace’ created is in service of the greater good of activism, rather than to protect the reputation of a faction and its most prominent figureheads. The glamourising and self-important lens through which each group sees itself makes it easy for the safety and respect of activist women and people of colour to be overlooked. The cycles of silence created force such people to face the difficult decision of ignoring their own grievances and remaining in a space that is hostile to them, or leaving their own faction, leaving them without personal and political support, and in most cases, pushing them out of activity. The uneasy silence around abusive behaviour have caused dozens of women to ignore their own grievances, disengage, or leave altogether.

I spoke to one survivor whom had chosen leaving altogether:

“Despite there being a general knowledge amongst our peers of the hurt that my ex had caused, there seemed to be no precedent to address it, at least from my perspective. Everywhere I turned, I saw the people I was looking up to, seemingly complicit in his behaviour, which only seemed to be continuing on its steady trajectory.

I was aware of the fact that there were grievance processes in place to address issues such as these. However, no matter how much I longed to feel as if I could call the space my own, it had gotten to the point where I did not feel as if there could be any possible outcome to the accountability process that would make this my reality. Too much time had passed, too much more had happened, I felt that I had no right to still be hurting, no right to disrupt the bonds and allyships that had formed long before I entered the scene. I believed then that I was being shown that it was not the right place for me if I could not move past this history. I decided to leave the space.

There is something so deeply rotten about this culture within the left. It is not a new story, for activist spaces – supposedly ‘safe’ spaces – to be the very ones which turn a blind eye to the pain being inflicted by their own members, to the misogynistic manipulation, abuse, and sexual violence that runs deep within its core. The cracks have always been there in the facade – it’s past time that we gutted this rotten culture, and lay a new foundation of genuine accountability, and radical healing for survivors.”

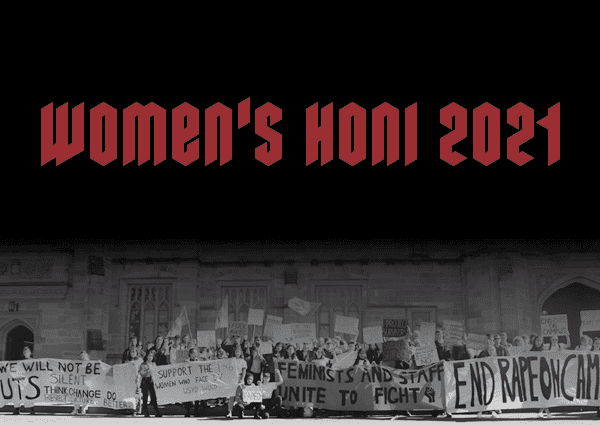

It is no coincidence that there is both a lack of leftist men at feminist rallies and a structural issue of sexism in leftist organising. I can count on one hand the number of male comrades that turn up to consent workshops, rallies against sexual violence on campus, or other WoCo events. Men don’t run grievance processes, men don’t check in on struggling comrades, men don’t step in when other men make sexist remarks. This is un-glamorous, unseen, difficult work done largely by women and non-binary people; not always because we want to, but because it otherwise won’t be done at all. When men do take this work on, it is after our own pleading and head-kicking. In these rare instances it is lauded as exceptional and a reflection of good character, though not when women or non-binary people do it.

Men do not show up in the streets, and they do not show up interpersonally. The disparity between praxis and one’s so-called politics is most obvious when it comes to men in the left not proving the anti-sexism they claim to believe in. It takes constant and active self-reflection to unlearn ingrained sexist behaviour – yes, even from leftists. Anti-sexism is not just a political identity, but a continuous call to action. These left-wing spaces can hardly claim such a title if the basic tenets of feminism are ignored.

Feminist organising on campus is not respected, nor are the Women’s Officers who lead it. Our specialised skills and knowledge in the intricacies of trauma, gendered violence, and feminist activism holds little value in the left. This has to change. Our specific knowledge and experiences are irreplaceable. Our work has spanned decades and positively impacted the lives of thousands of students. However, factional support has never been extended to women’s officers the way it has to many other major SRC positions. This is not unique to my term, but a trend that Women’s Officers before me can attest to.

What more do we need to do to gain respect? No other group or person on campus is criticised from the right and management quite like the Women’s Officers. Women’s Officers over the years have received countless disclosures of sexual violence, been doxxed by right-wing extremists, spat on and swung at by Nazis, threatened with violence and death, gone through many misconduct processes, suspended and expelled from campus, and rolled from their position by Liberals (only to continue to convene WoCo unpaid all year). This would be hard enough but the difficulty and isolation of this position is magnified by the attitude of the Left. Looking at recent history alone, Women’s Officers have been publicly belittled for making political critiques, have had their anti-sexual violence work deemed ‘irrelevant’ to ‘more important’ campaigns, and been met consistently with apathy when asking for help combatting direct far-right violence. This position is incredibly difficult and isolating, and needs more support from the comrades around us.

Many have contributed directly to this article, all remaining anonymous for their own wellbeing. However, I have truly compiled this article from months and years of more conversations than I can count, over many dinner tables, at the back of bars, after WoCo meetings, in hushed tones, in the raised voice of frustration, and through teary eyes. These are not just my encounters, but those of so many of us. I thank every person brave enough to share these experiences.

I believe in mass organising of the student left which prioritises feminist liberation is possible, if only the feminists leading it are respected and supported like they deserve. This week, both Women’s Officers will leave our faction due to structural sexism, just as the Education Officer, Maddie Clark, left hers for the same reason only months ago. I hope this article does not spur gossip, but sparks deep reflection amongst the campus left. I hope my comrades look around and reckon with the behaviour of their male comrades, notice the lack of female comrades — particularly women of colour and working class women — and ask themselves how their very own behaviour is impeding, or even opposing, the liberatory work we aim to do. Because without accountability, harm will only continue to shatter community, and “without community there is no liberation”.

Disclaimer: Kimmy Dibben and Amelia Mertha are former members of Sydney Grassroots.