Background

1970s Australia was swept up in the changing times of the rest of the world. The Anti-Vietnam War movement was gaining momentum, peaking in May 1970 when more than 200,000 people marched in a moratorium across Australia. It sparked discussions about the discrimination and oppression faced by other minority groups. Oppressed peoples began to link their struggle to the global fight against capitalism. In 1969, the Stonewall riots catapulted the plight of the gay community onto the global stage. Eschewing the mainstream view that being gay was a mental disorder, a sin, something to hide and pray away, the politics that came out of Stonewall and the Gay Liberation Front popularised radical politics, birthing the slogans “gay is good” and “out and proud”.

CAMP 1970

These politics had profound influence on the LGBTI+ community in Sydney, and on September 10 1970 the first queer activist group the Campaign Against Moral Persecution (CAMP Inc) was formed by neighbours Christabel Poll and John Ware. Their aims were simple: change the way homosexuals were seen in society, change the law, the medical profession and take on the church. The shame, discrimination and silence that surrounded queer issues would be tackled head on. Their first mission was to come out publicly, to show others in Australia that you could be okay, even proud, to be gay. This was groundbreaking. In a Christmas edition of their newspaper, CAMP Ink, the cover had the photographs of 35 CAMP members with the caption “We’ve come out of our closets to wish you a Merry Christmas”. Awareness precipitated growth, and in the first 12 months local CAMP groups had formed in every Australian city.

In any activist group, debates will inevitably emerge about strategy. This occurred in CAMP, with some prioritising protests and activism while others wanted to focus on culture and raising awareness. Despite these debates, actions were planned around Sydney. On October 6 1971, a protest to picket the Liberal Party Headquarters was organised. This was followed with pop up street protests and the opening of a new Sydney Gay Liberation Centre on Glebe Point Road in 1973. To reach out to school students they printed and distributed a hundred “Are you a Poofter?” leaflets which proclaimed: “It is stupid to believe that any form of love between people is a sin.”

In 1970, the Summary Offences Bill was passed which gave more powers to police to arrest demonstrators. It also meant that activists had to apply to the Police Commissioner for permission to stage demonstrations. While the gay community was far from equal in legislation and in society, gay culture in Sydney proliferated. CAMP activists learnt how to make posters in the Wentworth Building at Sydney University. A second National Homosexual Conference was held in Sydney in 1976. The city became a cultural heartland of LGBTI culture, with the Feminist Bookshop holding lesbian poetry nights, gay pottery workshops, social clubs like Gay Men’s Rap, and, of course, the gay clubs that littered Oxford St. As Lex Watson, the 1972 co-president of CAMP wrote in the gay edition of Honi Soit in 1976, “there is a certain paradox about homosexuals and the law in NSW. We have the highest per capita prosecution rate of any State. We also have much the most openly gay commercial world.”

1978

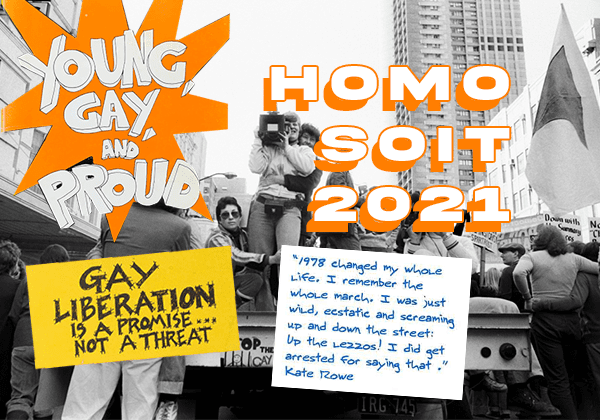

This all changed with Sydney’s first Mardi Gras. On June 28, 1978, the Gay Solidarity Group organised a day of activism to demand: the police stop harassing gay men and women, the government to repeal anti-homosexual laws and the Summary Offences Act, and to stop workplace discrimination to protect the rights of LGBTI+ people. What began as a 500 person energetic protest march ended in violence. 53 people were beaten, arrested and held in Darlinghurst Police Station’s cells in the most brutal systematic bashing of LGBTI+ people in Sydney’s history. The following Monday, the Sydney Morning Herald published a list of those arrested, destroying the lives of the people they had outed. That night changed things. As Peter Murphy, who was violently bashed said, “the police were trying to break our spirit… all of us were upset at the mass arrests and repression… but people didn’t let it break them. It was really a resilient movement.”

The crowd fought back, and on July 15, a 2000 person protest demonstrated for justice. Over the next few months a further 125 people were arrested at ‘Drop the Charges’ marches and by the next year most charges were dropped. The Summary Offences Act was also repealed. Importantly, the movement had now seen the necessity of defiant and confrontational activism. Many different political groups united around queer activism, with the more conservative elements of CAMP turning into counselling services. As 78er Margaret Lyons explained, “We couldn’t be put back in the closet. It was an affirmation that they couldn’t take away from us. More and more people came out saying “we’re gay and you can’t take it away. We’ve got a right to be out.”

Conclusion

While Mardi Gras was a unique turning point for Sydney’s LGBTI+ movement, it couldn’t have happened without the coming out and visibility of early CAMP members. In today’s context of the far right’s push back against queer rights, notably the Religious “Freedoms” Bill, we can take inspiration from history. The heroism and bravery that has been at the core of queer people fighting for their liberation extends from the 70s to today. Mardi Gras was a riot and we will win our liberation on the streets.