Senior management at the University of Sydney are no strangers to staff and students’ disdain.

In early March 2013, just under a year before retiring from a University Chair position, eminent sociologist Raewyn Connell wrote and circulated a letter addressed to then-Vice-Chancellor Michael Spence.

“With performance management, online surveillance systems, and closed decision-making, it appears that the university authorities these days don’t really trust the staff – to know our trades, to act responsibly, or to share in running the place,” she said.

“The very last thing a university needs is an intimidated and conformist workforce.”

It was the end of Week One, Semester One, and university staff were on strike for the first time since 2003.

Industrial action at USyd: the past and present.

Today, sometimes multiple times a week, ardent contingents form outside Fisher Library or the immediately recognisable Quadrangle. Long-time staff members and enthusiastic first-year students alike show up, impassioned against ongoing university austerity measures; the cutting of subjects, hundreds of staff, and entire schools.

These efforts were sustained even in the throes of lockdown, with activists gathering in small groups in accordance with social distancing restrictions, only to be met with a heavy-handed police response which would disperse, and in some cases assault, attendees. Academics held teach-ins, and in 2020 students held a storied six-hour occupation of the F23 Administration building in which USyd’s senior managers reside.

While attacks on teaching and learning conditions are endemic to USyd, so is the willingness of its learning community to fight back, not just for ideal or so-called ‘ambitious’ conditions – but for the bare minimum. Basic sick leave entitlements and yearly pay increases to keep up with the rate of inflation became the subjects of tense negotiations as livelihoods were won on the strength of staff organising.

These education campaigns and protests are usually waged by academic and general staff who are members of the National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU), and are supported by student activists and members of the public. In the last decade, staff have gone on strike twice in 2013 and 2017 respectively, during the University’s Enterprise Bargaining Agreement (EBA) period where the NTEU negotiates wage and employment conditions with University management every four years.

Current USyd NTEU Branch President Nick Riemer is enthusiastic about the role students have to play in supporting staff, repeating the oft-cited aphorism that “staff working conditions are students’ learning conditions.”

“We want classes to be less crowded, we want staff to not be casualised and be on decent conditions, to be given the time they need to do research in their disciplines… All of these things are key union demands and have an obvious impact on the student experience in the classroom,” Riemer says.

The strike that kicked off in 2013 was the culmination of a months-long stalled bargaining process the year before, during which staff claims were minimised and demands routinely ignored.

Michael Thomson, USyd Branch President of the NTEU from 2003 to 2016 and NSW Secretary of the Union until April of last year, considers it one of the most aggressive negotiations he had seen in close to 20 years at the bargaining table.

“People work at universities not to make money, but because they think education is a public good: it’s socially important. Then, they get treated like this,” he says.

“[The proposed 2012/13 agreement] was a real strip-back, things like intellectual freedom and overtime were removed. It showed the lack of understanding management had of university staff, things like workload weren’t important to them.”

The EBA period also came in the wake of assorted academic job cuts in 2011, which the union fought largely successfully. The response of industrial action in 2013 – strikes during Week One, Open Day and later in Semester Two – Thomson recounts, wasn’t a course of action that was taken lightly.

Under current legislation, unions are obliged to seek authority from the Industrial Relations Commission in order to conduct a ballot. For an action to go ahead, more than 50 per cent of union members have to respond, and a majority have to say yes.

Riemer is firm on the power of prospective strikes during the current EBA period and on the motivations that underpin action itself.

“An employer’s power is particularly arbitrary in the sense that, in exchange for a salary, we essentially forfeit our autonomy for the period of our employment… Withdrawal of labour is the principal means that employees have of exercising their agency when other avenues of negotiation have failed,” he says.

The outcome of the 2013 actions was mostly positive, with union members endorsing an agreement in October that saw them receive a sufficient pay rise, three paid research days per year, a sign-on bonus of $540 and the creation of 120 new positions, among other claims. Thomson says that the process behind compiling a ‘log of claims’ to present to management is reliant on a rigorous internal democratic process, comprising meetings, debates, amendments, a survey of members’ concerns and consultation with branches at other universities.

“When you went to management and gave it to them, your members had ownership of it and, therefore, bargaining power,” he says.

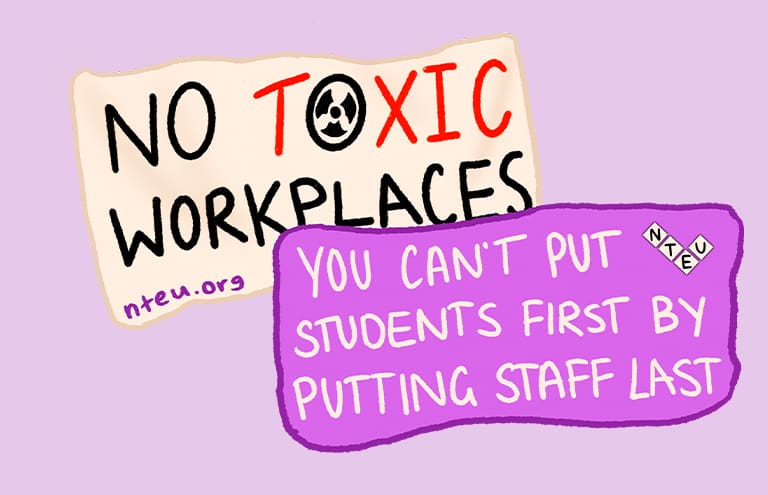

While the strikes in 2017 brought less attrition, the conditions and demands were all too familiar. Staff stood up against the University’s unwillingness to grant pay rises, reduce forced redundancies and casualisation, and preserve the ‘40:40:20’ percentage split of staff workload between teaching, research and administrative work. Then-Branch President Associate Professor Kurt Iveson wrote a year later that staff were, and continued to be “driven to despair by a toxic combination of insecure work, workload intensification, and corporatisation.”

Thomson breaks effective industrial action into the effective targeting of three outcomes. The first is making sure that union members themselves feel confident and involved, especially if there is potential for further action. The second is having an impact on university management; that the prospect of striking is real.

“You’ve got to make it clear to them that you’re not going to be treated like dirt. You’re not going to be ignored in a stand up and, if necessary, you will actually shut down teaching, you will shut down a whole lot of what the university is about,” Thomson says.

Third is creating solidarity between strikers and the wider community. A strong action illustrates its importance at events like Open Days, disrupting the glistening public image the University tries to project so as to illustrate the truth:

“The reason you’re aggro is because management is treating you with disrespect,” Thomson explains.

Today, years of remote teaching during the pandemic and extensive casualisation throughout the sector could threaten that solidarity. Last year, Honi reported extensively on the insidious impacts of casualisation at the systemic level; universities are not obliged to provide leave entitlements, and the piece-rate structuring of payment essentially ensures that casuals are exploited and overworked when marking assessments.

Further, scant requirements on how universities report their employment data leaves the extent of casualisation and job losses across NSW’s public universities unclear – though it’s estimated that, at the very least, half of academic university staff are casual employees. Given universities are unwilling to even report their casual employment statistics, it is clear that casual employees are often the first to be sacrificed in service of financial ends: a tranche to cut loose in the event of a government policy change or revenue shortfall due to a drop in international enrolments.

Not being able to know the scale of the problem makes it exceptionally hard to organise against it and, as Thomson argues, weakens the union movement itself.

“Clearly, it hurts the people who are casuals and who can’t get ongoing employment, but it also breaks down that sense of community. Casuals can sometimes be working at two or three different universities. Some don’t even have their own desk,”

“I’d be surprised if, at many universities in this next round of bargaining, there wasn’t industrial action,” he says.

On the ground, Thomson is resolute that the path forward is to simply to keep campaigning, building union power both in scale and across other public sectors in the face of obstinate management systems and combative government policy.

“I think at the moment, we’ve got a government that prides itself on anti-intellectualism… They have no appreciation of why education should be available for everybody and should be free for everyone,” he says.

Yet, the persistence of these conditions nevertheless brings into question if a better future is even possible.

Building staff power

Looking at the long-term, systematic mistreatment of staff in universities, one wonders: why are these issues so entrenched? And can we ever expect them to change?

Dr Michael Beggs, an academic in the Department of Political Economy and a member of the NTEU’s Enterprise Bargaining Team, characterises the intensification of staff workloads and rise of job insecurity as a “pressure valve”. University management, responding to the financial imperative for surpluses, squeezes extra value out of overworked and underpaid staff.

Beggs suggests that the diversity and complexity of academic work – which typically involves research, teaching, and administration – means it is far less “concrete and easily quantifiable” than financial outcomes. As a result, managers engage in “magical thinking” about academics’ capacity to manage their workloads sustainably, underestimating the time it takes to complete their given tasks.

Professor John Buchanan, an Industrial Relations researcher and member of the Enterprise Bargaining Team, adds that complexity poses new challenges to labour organising.

“It creates a challenge of solidarity… it’s hard to build a simple, mobilising narrative; you’ve got to think very hard about how you put together priority issues that will address a diverse audience but bring them together around common concerns,” Buchanan says.

One common thread through the array of iniquities facing staff is that the priorities of the University often seem irrational. Workload and job security issues erode the quality of teaching and learning. Where educators are pressed for time, they have to pick between completing research, marking, course preparation and supporting students.

Similarly, Beggs argues that it is pedagogically and organisationally problematic to uncouple the research-teaching nexus by creating teaching-only roles and forcing staff to individually negotiate their research and teaching time.

“One of the benefits of the combination [of teaching and research] is we keep across the field and we can use research to feed into teaching… [Compromising this] means people get burnt out quickly, they feel like they’re doing a disservice to their students,” he says.

On a financial level, it is also unwise; although it is cheaper to pay people only to teach, it relies on academics committing to unsustainable and unsatisfying academic labour, stretching staff thin. Moreover, Beggs explains that government funding to universities is tied to the cost of delivering courses per student:

“[Cost-cutting is] setting the University up to be squeezed further in the future… if the costs come down, there’s nothing to stop funding from coming down with it.”

There are two main problems underlying this state of affairs.

First, creeping neoliberalism and ‘small government’ ideologies have permeated tertiary education. Buchanan explains that governments have “walked away from funding [universities] properly… that’s where you get these kinds of pathologies.” Similarly, Beggs suggests that university management – albeit not publicly – feels it is between “a rock and a hard place”, where the drive to remain in surplus is placed under stress by stagnant funding. Beggs stresses that the University is in a relatively solid financial position despite COVID-19, but nonetheless is structurally geared to “take the easy way out” by seeking uncompensated productivity gains from staff.

This right-wing policy environment also produces the conditions which constrain staff power; a viciously constrictive industrial relations landscape where, despite enjoying relatively high levels of public approval, a hostile legislative environment constrains unions’ options.

Addressing this will require sustained union energy to reverse the disempowerment of the sector’s workers. More broadly, support for fully-funded public services, where the urge to cut costs is limited and funding is not contingent, is vital. The fight for workers’ rights at universities and the need for quality, universal education are inherently intertwined.

Second, past decades have seen a shift in decision-making power within the workplace through the rise of managerialism. Where previously, doctors ran medical boards and academics ran universities, institutions are now controlled by specialist managers whose expertise lies in managing money rather than the field they’re working in.

This makes it easy for managers to concoct unrealistic expectations around staff workloads, which is why a key NTEU demand is for “realistic and evidence-based” metrics for staff workloads, requiring the university to “trust academics on how long it takes to do things,” Beggs says. The NTEU is calling for staff workload committees to have union-appointed or elected staff representation, rather than the current system of appointments by the relevant Dean. Meanwhile, the University wants to go further than the status quo, aiming to abolish workload committees altogether and leave negotiation to individual workers and managers.

Professor Buchanan describes the current system of managerialism as an “attack on expertise”, but warns against romanticising past systems. Instead, he sees the bargaining process as a way to “think through how you would create a quality system”.

Industrial action is an opportunity for academic workers to develop and advocate for a positive vision of the University; one where they are compensated properly for their time, and one where the financial imperatives of senior managers do not undermine the long-term integrity of the institution.

Looking beyond the university

The University of Sydney is a big player in tertiary education, which itself is a big industry in the Australian economy. How, then, might industrial action at USyd have broader significance for Australian workers?

“I wouldn’t say universities are regarded as wage leaders,” Professor Buchanan says, but USyd is “influential within the university sector.” While workers across the labour market face a host of restrictions on industrial action and legislated wage caps, making strong arguments for workers’ rights remains important: “these are tough times… You’ve got to be very clear about what it is you’re campaigning about, what you dispute about”

Dr Beggs suggests that, from a macroeconomic standpoint, the Government is passing up an important opportunity to use the public sector to shape the economy: “public sector jobs… absolutely have a really important role to play in setting the pace in wages and conditions in the private sector as well. They hire from the same labour market. If the private sector has to compete it has to have an impact [on conditions].”

In the context of a pandemic, cost-cutting has the “macroeconomically speaking, irrational” effect of suppressing spending, as workers face low wages and uncertain hours, Dr Beggs says.

It is clear that, across the public sector, essential workers experience ever-escalating pressure. These workforces are treated as shock absorbers for systems under stress, asked to do more work for less pay and disheartened by the attacks on their profession. As we see nurses, transport workers and educators striking, it is a sign that rampant neoliberalism is wearing thin; the unsustainability of treating workers as a pressure valve is coming into focus.