CW: discussion of sexual assault.

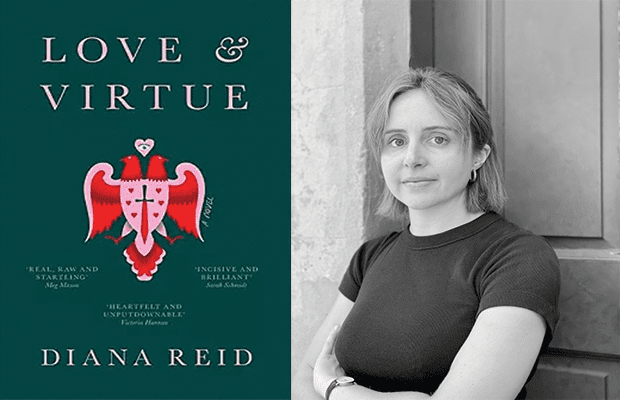

Last Monday, Sydney University alum Diana Reid appeared at a Philosophy Society event to discuss her debut novel, Love and Virtue. The novel, and the discussion, engaged in conversations about sex and consent on campus.

Love and Virtue is a coming-of-age novel set in a residential women’s college that questions privilege, consent and morality, depicting the tensions between contemporary relationships and personal integrity.

Reid interrogated how philosophy can inform our thinking about relationships. “So much of moral thinking is emotional,” she told guests. Where philosophy theorises our emotions, literature and fiction enables readers to engage intuitively and experientially.

There are two major violations of consent in the novel. The first is a sexual assault, the other, the theft of a personal story. When asked if there was room for ethical ambiguity when it came to consent, Reid responded with, “I think we should strive to appreciate moral ambiguity.” Leaving room for nuance instead of ascribing things into black and white terms can be helpful when engaging in heavy conversations.

The novel’s two main characters, Michaela and Eve, hold a tense and ambivalent friendship, marked by an underlying competitive streak, under the guise of womanhood and ‘supporting our fellow sisters’. Where Michaela represents moral uncertainty and is defined by her class as a scholarship-student, Eve, with a background of family wealth, wears her conviction on her sleeve, vaunting her unmarred ethics with exorbitant sustainable fashion purchases. This conviction can be dangerous and risks conflating being ‘good’ with being a ‘better person’.

The friendship is splintered by the pair’s class difference. Reid cautioned against conflating moral certainty with objective goodness. Eve’s character is a prime example of this conceit. Despite her class privilege, she directs outrage at anything she considers immoral and espouses progressive theoretical critiques. Eve’s moralistic tendencies are polarising. Performatively, she employs ‘shock factor’ quips to provoke reactions, like her performance of masturbation in a college monologue skit and her return from Europe with a shaved head as a supposed rejection of the conventions of beauty.

The popular trope in campus novels about the abuse of power in institutions and the predatory nature of illicit affairs is illustrated in the relationship between philosophy professor Paul Rosen and Michaela. He is nearly twice her age and ironically teaches classes on ethics. Eve looks at the student/professor dynamic through the lens of the patriarchy in moralistic terms. She maintains that the relationship between Professor Rosen and Michaela is completely wrong and fails to empathise or support Michaela as a friend. Instead, her absolute conviction leaves her isolated.

Reid reflected on her own experience at uni, where being ‘woke’ equated to social capital among her peers. Although being critically informed about the socio-political world is undeniably an admirable trait, she critiques the way ‘wokeness’ is weaponised to belittle others and secure a moral high ground, especially when so much of our depictions of wokeness rely on inaccessible and expensive symbolism.

Reid was asked if she sees a future for residential colleges, in light of their endemic sexual violence. She responded that colleges, as institutions, are made up of the people within them and their politics. Reid’s softness towards the colleges and suggestion that anti-college sentiment engages in sensationalism is difficult, considering the indictment of rape and sexual violence against women at colleges within her novel.

This position also goes against the ‘Burn the Colleges’ stance taken by the student Left and radicals at USyd this year, who’ve argued that the College institution is rife with misogyny, sexism and reflect privilege and rape culture on campus. Former Women’s Officer Madeline Clark said in a speakout against sexual violence: “We’ve been telling the University for many years that sexual assault is rife on campus, particularly on the colleges.”

The National Student Safety Survey (NSSS) released this March found that 1 in 20 students have been sexually assaulted since starting university, and that half the students surveyed knew nothing or very little about the formal reporting process for harassment or assault. Welcome Week is known for ritual hazing and ‘traditions’ that involve grooming new students. According to The Red Zone report produced by End Rape on Campus Australia, St Paul’s College was alleged to have hosted ‘Bone Room’ parties; alcohol and drug-fuelled sex gatherings where men would invite the most attractive women to their rooms and instruct them to dress in theme before engaging in sexual activities.

Reid also referenced linguistic philosopher Rebecca Kukla, whose research on consent explores the nature of a request and how language is used in a variety of ways to negotiate initiating sexual activity. If someone denies your request, the nature of your response is to feel upset. However, if you invite someone to do something, and they say no, you’re not entitled to feel upset at them. The analogy of choice and invitation within the pragmatics of speech intrigues me.

Reid notes the importance of sensibility and empathy to hold conversations like these. She quotes Amia Srinivasan’s The Right to Sex, affirming that “Sex should leave you more human at the end of it.”