Regardless of the actual utility of philosophy, there is no question that the discipline is often criticised for lacking practical relevance. As a second-year philosophy student and having had interest in the subject for a few years, I naturally take issue with this stereotype. Whether this is a rationalisation to justify the value of my passion or not, I suspect this scepticism is rooted in the neoliberal logic of education which conceives of education merely as a conduit for the workforce.

Some of the best lecturers I’ve seen at university have been in the Philosophy Department. Courses like PHIL1011: Reality, Ethics and Beauty are widely appreciated across the University. Owing to the popularity of former lecturer Dr Sebastian Sequoiah-Grayson, PHIL1012: Introductory Logic set a record for enrolments in a single Arts and Social Sciences course last year. Despite students’ efforts in an impassioned campaign to have his contract renewed, it failed and the superstar academic found greener pastures at the University of New South Wales. Now a tale in the University’s history books, it made me curious about other forgotten stories of the department that may lay hidden behind the sandstone walls.

Internal Political Struggle in the 60s and 70s

Philosophy itself is notorious for having eccentric characters, so it’s no surprise that the Department at Sydney University has its own colourful history. In the 1960s and early 1970s, the Department was caught in a quagmire of big personalities and political tensions culminating in an infamous split in 1973. Though it had curiously low coverage in mainstream media, an Honours paper by David Rayment, The Philosophy Department Split at Sydney University 1964-1973 (1999) retains an extensive record of the debacle.

Almost thirty years after the drama, former philosophy lecturer John Burnheim described the time as a “very confused conflict” which ultimately boiled down to an ideological schism between conservatives and boundary-pushing radicals. The conservatives included David Armstrong, appointed Challis Professor of Philosophy in 1964, and David Stove. In 1988, Stove wrote an essay called ‘Why You Should Be A Conservative’ which made clear his conservative politics.

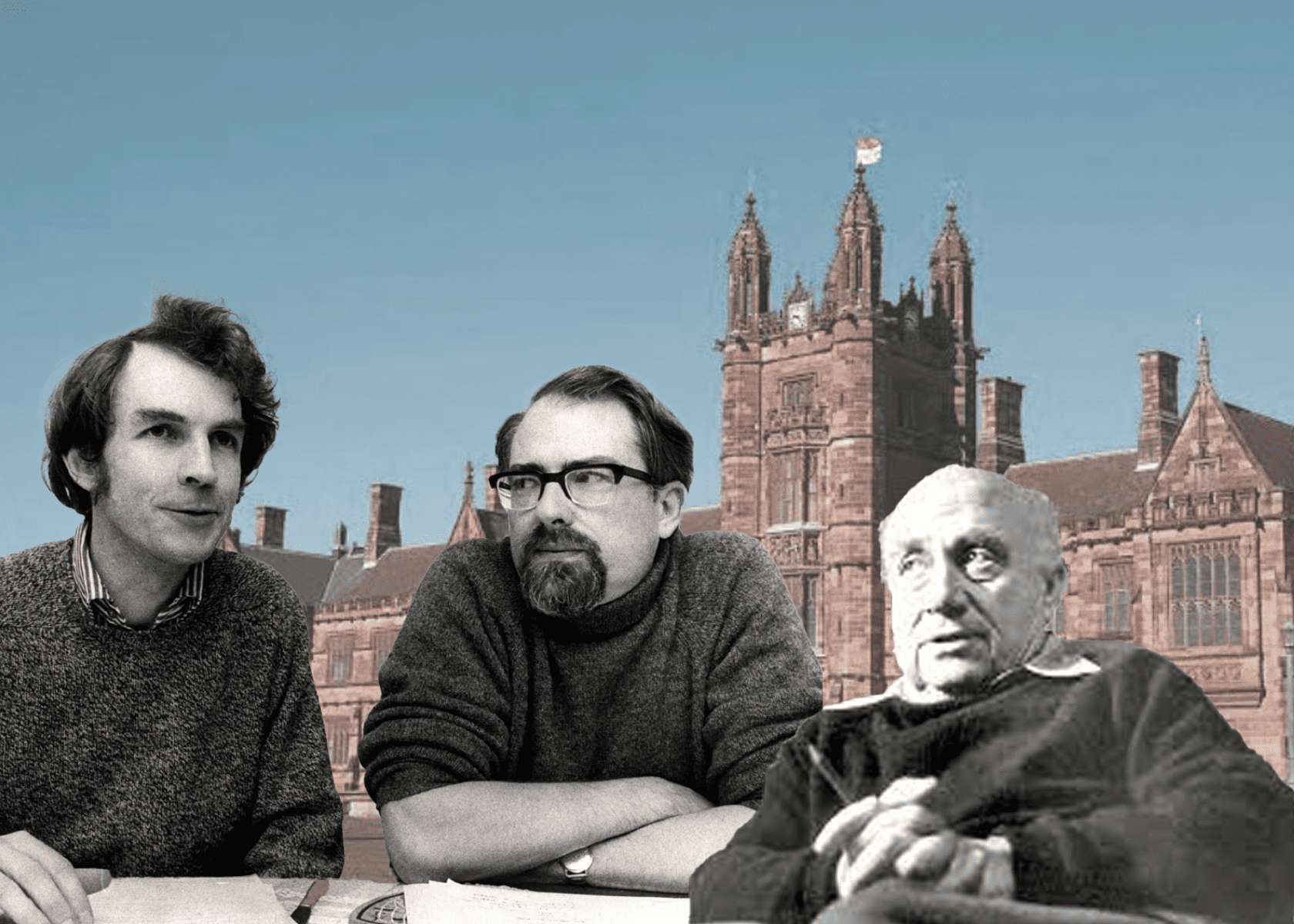

On the other hand, the radicals included Wal Suchting and Michael Devitt who were very much rooted in Marxist schools of thought and advocated for more overtly political approaches to philosophy.

Michael Devitt (left) and Wal Suchting (right) (Source: Corrupting the Youth: A History of Philosophy in Australia)

The first point of tension was known as the Knopfelmacher Affair over Sydney’s appointment of Frank Knopfelmacher, a polemic figure known for offending the Left. For Armstrong, this was a chance to push back against communism and the growing presence of the campus Left.

On the other hand, the Left were motivated to keep Knopfelmacher out, with Suchting using his connections in Melbourne to consistently uncover dirt on Knopfelmacher. Armstrong recounted faculty member George Molnar saying “people in Melbourne kept sending Wal (Suchting) the dirt on Knopfelmacher”. Knopfelmacher was not appointed, which ostensibly confirmed the Right’s narrative that the University had become overrun by the Left.

In fact, it is poignant that the same problems of the University that have been driving the recent campaigns against the staff and course cuts seemed to be echoing the more “radical” wing of the Department at the time. Molnar, a self-described pessimistic anarchist, wrote an open letter for Honi in 1967 condemning the flaws of the institution: “For too long both teaching and administrative members of this university have maintained an effective isolation, have cultivated silence, secrecy, have been slow and ungracious in offering accounts of their doings. It is not that students are alienated from us, it is we who are alienated from them.”

The Left in Australian philosophy

That being said, the rise of the Left in Australian philosophy departments was not insignificant. The first shift was at Flinders University where the Head of the Department, Brain Medlin, was one of the leaders of the anti-Vietnam War movement in Adelaide. Medlin cancelled a week of lectures, resisted arrest and was incarcerated for refusing to pay fines. At the 1970 Australasian Philosophy Conference, he draped a red flag over the lectern before giving his speech following the passing of a motion condemning the Vietnam War.

Despite this progressive shift, conservative fear mongering surrounding the “politicisation” of universities festered. In 1971, Armstrong chaired a talk hosting the First Secretary of the South Vietnamese Embassy. A student named Hall Greenland took the microphone and heckled the speaker, calling them a “worm”. The incident saw Armstrong physically intervening to seize Greenland’s microphone. Due to the altercation, Armstrong was nicknamed “The Beast”.

David Armstrong seizing Greenland’s microphone (Source: Corrupting the Youth: A History of Philosophy in Australia)

Despite Armstrong and Stove’s efforts, Sydney Philosophy continued to radicalise. In 1972 and 1973 Suchting and Devitt proposed courses in Marxism-Leninism teaching the philosophy of Stalin, Ho Chi Minh, Mao, and Guevara. Though the courses were passed by a 10-3 vote, Armstrong tried to veto this with the powers he held as Department head. Suchting, Devitt and other staff members organised a meeting with several hundred students to speak against Armstrong’s overreach. They penned an open letter in Honi: “Today, in each university, there are people who see it as their job to prevent Left groups destroying universities and subverting schools. Ten to fifteen undergraduates form into a ‘Peace with Freedom’ group.”

Eventually, they struck a compromise, including the withdrawal of the writings of Stalin, Mao, and similar figures from the reading list to the general bibliography. Marxism became a new course.

However, tensions remained high and in 1972 there was conflict over the appointment of a new left-leaning tutor, Patrick Flanagan. Armstrong had misrepresented Flanagan’s competency suggesting that another staff member, Professor Spann, had rejected him when Flanagan had been running seminars in Spann’s Honours courses. In response, Devitt sent a private letter to another staff member writing, “It is now clear that the Beast [Armstrong] will not leave any of us in peace. It seems necessary that he be discredited & driven from the University. I shall henceforth support any tactic (within certain limits) that seems likely to help the achievements of this end.”

Devitt’s letter landed in Armstrong’s lap and he published it in the Sydney Morning Herald, even being read out by Liberal MP Peter Coleman in the NSW Parliament — this seemed to confirm the Right’s suspicion of a conspiracy against Armstrong.

As riveting as the stories of this internal struggle were, the 1970s was a time of radical pedagogical change. In 1970, fourth year philosophy students at USyd had a dope-smoking and heroin-shooting group for one.

Philosophy also enjoyed a vast degree of autonomy. The first step towards democratisation was in 1972 when the faculty decided on having student representatives in the Curriculum Committee. By the end of the year, voting rights were granted to all philosophy students meaning that students enjoyed considerable influence over the curriculum. Furthermore, teachers enjoyed free rein in deciding how to assess their students, meaning that they could eschew formal assessments.

Before the Department’s split, there was a final moment of controversy. In 1973, two graduate students, Jean Curthoys and Liz Jacka, proposed a course on ‘The Politics of Sexual Oppression’. Although the course received overwhelming support from the Department and the Faculty of Arts, the Professorial Board swiftly rejected the move. Staff and students responded with strikes and disrupted lectures in several Departments over several weeks.

Strikers pitched tents in the Quad and pickets were set up in lectures of staff who weren’t striking, including Armstrong. The strikers won and the course was approved. Celebrations were stuff of legend. Late Australian writer Frank Moorhouse recounts that there were “four-gallon casks of wine” excluding spirits and beer because the latter was too closely associated with “Australian male behaviour”.

“We talked briefly with George Molnar, a lecturer in philosophy who had been centrally active in the strike. He was making the ‘goodies’ in the kitchen (not savouries),” Moorehouse wrote. “ ‘Tomorrow the World’,” he [Molnar] said.

Victorious strikers sang their hearts out under the banner: “Philosophers hitherto have only interpreted the world — the point now is to change it.”

In light of this valiant idealism, the conservatives capitulated. Instead of vying for control over the Department, through the starpower of figures like Armstrong who was a leading philosopher of mind, the Vice-Chancellor acquiesced. On 2 October, 1973 the Department finally split into two. Devitt, Suchting and other leftist philosophers remained in what was known as the Department of General Philosophy. Armstrong and six other staff members formed the Department of Traditional and Modern Philosophy. However, this was certainly not the end of this story. For example, students in the fully-democratic Department of General Philosophy voted against formal exams.

It was not until the turn of the millenium that the Departments were finally reunited. Associate Professor Dr Luke Russell reminisces, “I remember when these two Departments merged to become the single Department of Philosophy that we have today. Some people were unhappy about this, but the Department has flourished.”

Instead, Russell praises the flourishing Department with members of the faculty actively involved in contemporary political discourse. Dr Luara Ferracioli and Dr Sam Shpall have recently published media pieces on issues like feminism, free speech, COVID restrictions, and cultural appropriation. Though now a thing of the past, the fraught period of the Department’s history remains a captivating tale of staff and student power. Philosophy may be written in ivory towers, but we make it happen on the streets.