Australia’s universities together have amassed over $100 billion in assets for the first time in history, making 2021 one of the most successful years on record for the sector.

Analysis conducted by Professor Frank Larkins, Emeritus Professor of Chemistry at the University of Melbourne (UniMelb), has revealed that Australia’s most prestigious universities reaped dramatic profits following last year’s lockdowns.

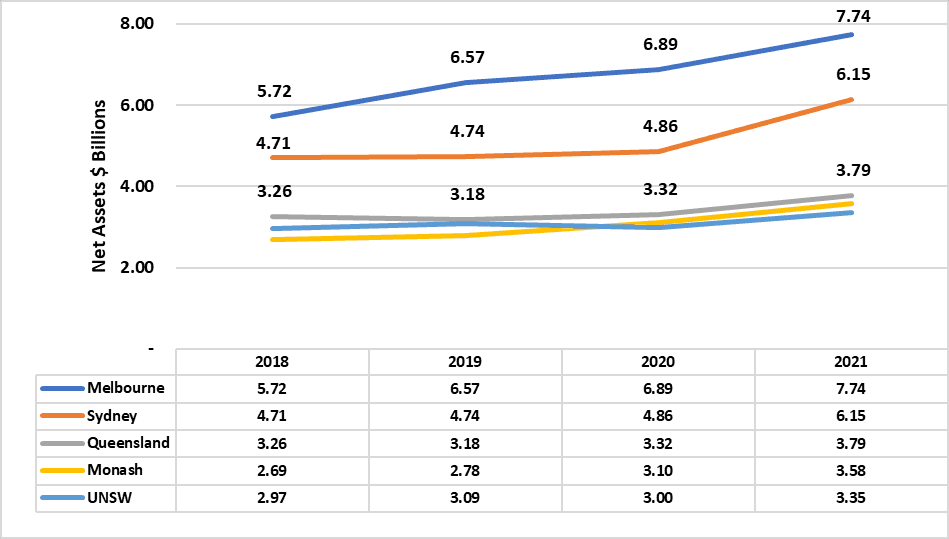

Five institutions – UniMelb, the University of Sydney (USyd), University of Queensland (UQ), Monash University and the University of New South Wales (UNSW) – collectively posted combined assets reaching approximately $37.3 billion.

Between 2018 and 2021, assets held by Australia’s 37 public universities grew by a staggering 24 per cent. Of the major universities, Monash had the highest asset increase, leaping by 45 per cent in the four years. UniMelb, overall, clinches the title of Australia’s wealthiest university by asset, holding $10.59 billion in assets — more than $1 billion higher than second place rival, USyd.

Net Assets for Five Majors Australian Universities from 2018 to 2021 in billions of dollars. Source: Professor Emeritus Frank Larkins, The University of Melbourne.

Just four years ago, the five institutions – colloquially grouped as the ‘U5’ representing the universities in the Group of Eight (Go8) commanding the lion’s share of research funding and student fees in Australia – held $11.8 billion. This means that, despite the impact of COVID-19, Australia’s major universities have almost all significantly increased their wealth compared to before the pandemic.

USyd enjoyed a drastic rise in its endowment funds from $2.2 to $3.3 billion between 2020 and 2021, and returned one of the highest increases in assets. USyd, together with the other four universities, attained a net asset growth of 27 per cent, from $5.72 to $7.74 billion.

In a press release, Professor Larkins said: “The sector growth of 18% supports the conclusion that the sector has performed financially better than most forecasts.

“Collectively, their total assets increased by 30% throughout the challenging COVID-19 pandemic years compared with 24% for the whole sector.”

Some universities cry wolf amid record profits

Despite Australian universities’ unprecedented wealth, some, like UniMelb, are warning that dire finances may be looming for the institution. Last year, UniMelb made one of the more significant surpluses in the sector – more than $126 million.

UniMelb Vice-Chancellor Professor Duncan Maskell told The Age that, compared to pre-pandemic years, he expects “a large operating deficit for 2022”, projecting the losses to total some $1.4 billion between 2020 to 2024.

Speaking to Honi, incoming SRC President Lia Perkins highlighted systemic wage theft across Australia’s universities.

“Universities are extremely wealthy institutions as a result of stolen wages, overwork from staff and exorbitant student fees,” she said.

“It is clear that universities did very well out of the pandemic, so there is absolutely no excuse for such wealthy institutions to not pay staff properly.”

Perkins’ concerns reflect this year’s spate of investigations into wage theft in higher education, disproportionately affecting casual academics across Australia. According to the Fair Work Ombudsman’s 2022 annual report, wage underpayment was rampant in tertiary education, with the agency scathing of many universities’ lack of funding and due diligence in managing payroll systems.

“Our intelligence indicates that underpayment has become systemic in the sector,” a press release from the Ombudsman said.

“Preliminary findings have revealed poor governance and management oversight, and a lack of centralised human resources functions and investment in payroll and time-recording systems have contributed to widespread underpayments by universities. Casual, insecure employees are commonly impacted by the underpayments.”

Indeed, the Ombudsman commenced legal proceedings against UniMelb after they allegedly coerced and threatened two casual academics seeking to be paid for work outside their contracted hours.

In response to concerns surrounding universities’ wage theft, a USyd spokesperson said that its eye-watering $1.04 billion surplus is “a one-off and result of savings measures we put in place at the start of the pandemics” alongside one-off investments, endowments, donor gifts and property sales. USyd, similar to a few other universities across the country, also recorded a rise in international student numbers, contrary to projections during the pandemic.

The spokesperson also said that, as part of the ongoing negotiations between the University and the NTEU, it has proposed “an additional 300 academic positions over the lifetime of the Agreement”.

Should USyd’s proposal be realised and applied to USyd’s last position in 2021, the additional 300 academic positions will increase academic staff numbers from 3514 to 3814 in absolute terms and alleviate the student-to-staff ratio from 21 to 19.5 students per academic staff. However, the figure that USyd proposes looks set to fall short of the pre-COVID-19 figure of 17.4 students per academic as USyd requires at least 750 additional academics to return to 2019 levels.

“We are also undertaking an evaluation to ensure consistency of work allocation and payment practices for casual academic staff across the University. We have kept the Fair Work Ombudsman informed of the steps we’re taking to resolve these issues.”