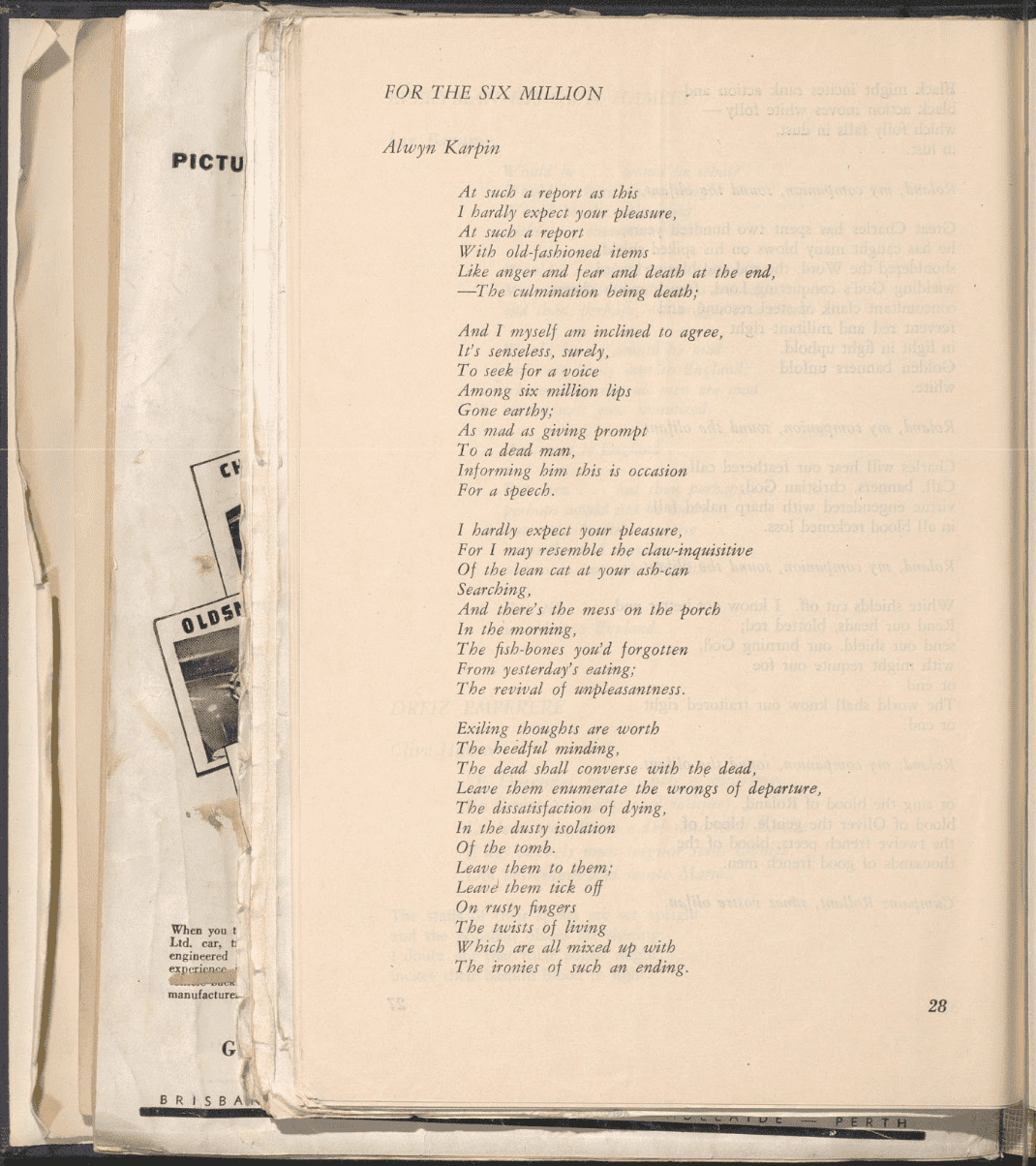

A poem ruminating on the horrors of the Holocaust may seem an unlikely place for this story to begin. But it is this poem — written and published in 1949 — where Alwyn Karpin so carefully articulates a profound connection to the events that unfolded thousands of kilometres from Sydney, that led to his meeting of Phyllis Perlstone. In fact, it is the existence of Hermes, Australia’s oldest literary journal, that brought these two together.

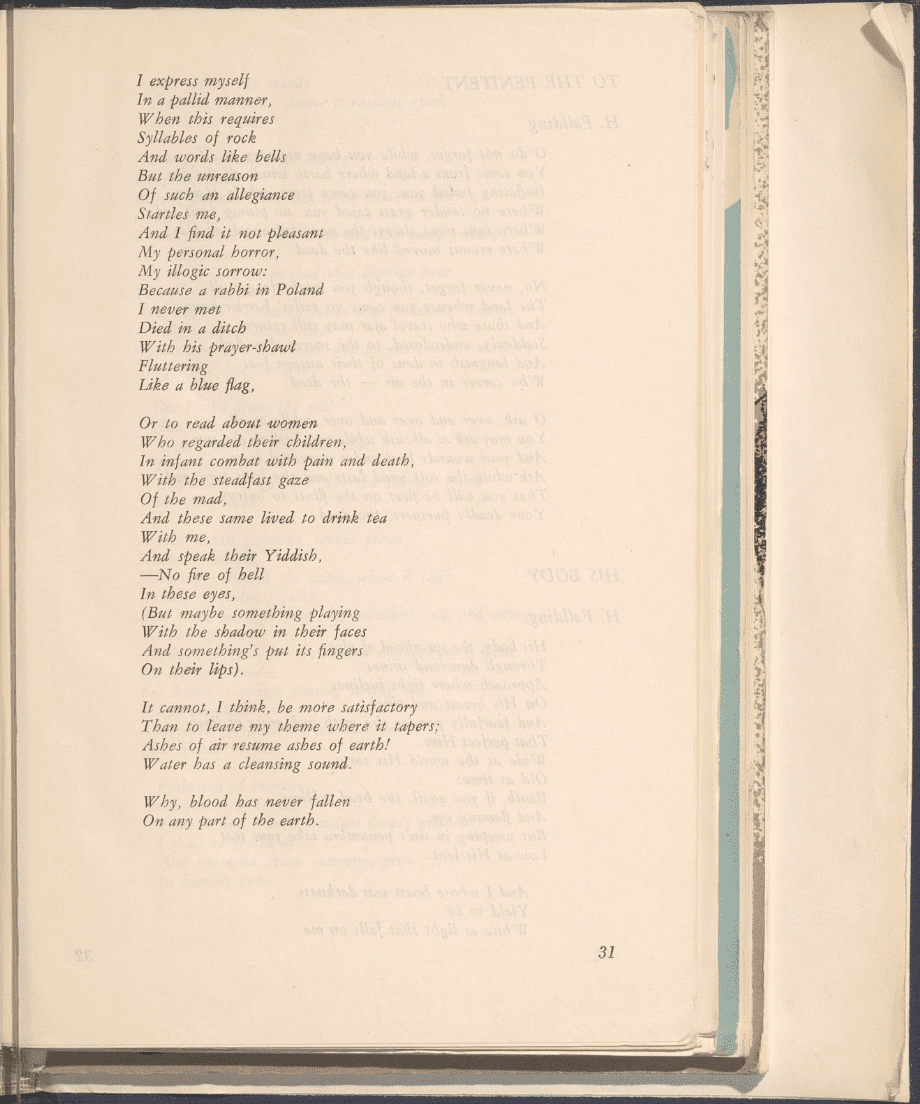

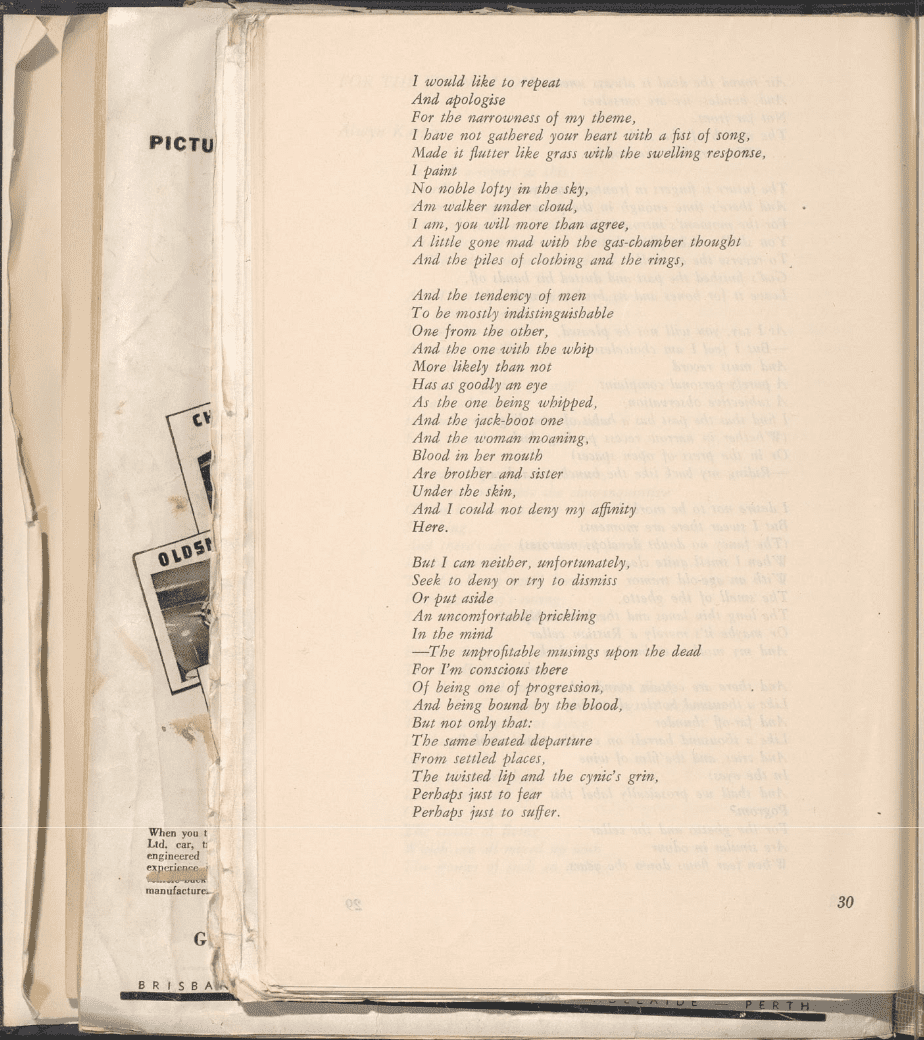

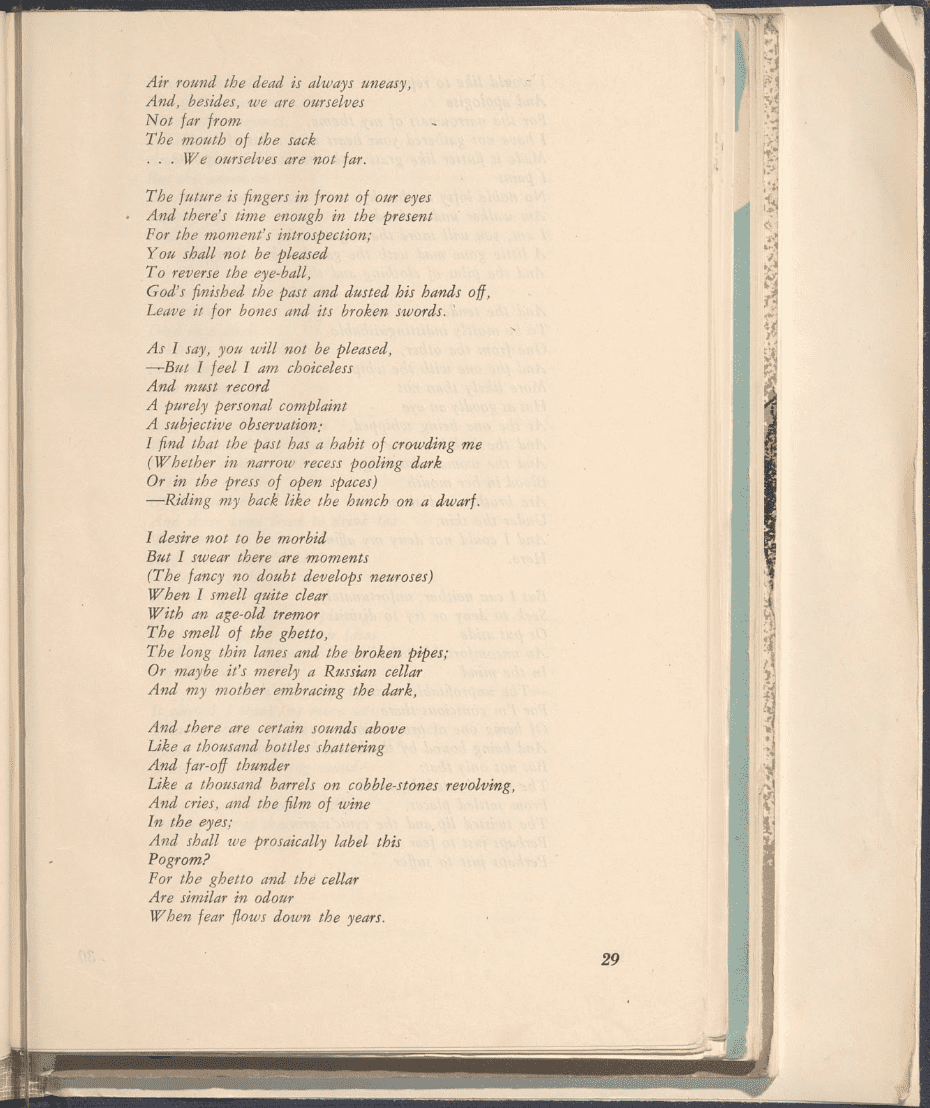

Alwyn penned ‘For the Six Million’ at 19 years old. His mother and father, both of Eastern European Jewish background, immigrated separately to arrive in Australia in the 1930s. The poem communicates a co-existing experience of connection and disconnection. The Holocaust, as a coordinated effort to eliminate Jewish people, forced Alwyn to confront his identity as an other. Despite being remote from the war, and his very limited connection to Judaism as a religious practice, the poem reveals someone trying to make sense of a kind of relationship that is not impacted by geographical distance. His unease with the subject matter emerges in interruptive apologies for the “narrowness” of his theme or his “pallid manner”. As he traces his own relation to the subject, the poem is given a sense of dynamism, his thoughts finding articulation in clever metaphors. The unbearable shock of events just unfolded rings through his lines.

Alwyn’s poem would eventually be read by Phyllis Perlstone, a 17 year old first-year arts student. She worked hard to win a scholarship that financed her university education, choosing to study English, Philosophy, and Psychology. Recalling her experience, she described herself as an adamant non-conformist, finding so many of her assigned English readings dull and predictable. Unsurprisingly, these observations weren’t appreciated by her professors. It was Sylvia Plath who fuelled Phyllis’s passion for poetry; Plath’s mocking tone, and sardonic critique of what women might “aspire to” that gave shape to Phyllis’s understanding of how poetry could give voice to struggle.

First published in 1886 by the Sydney University Union, Hermes was an annual literary journal that fostered the creative desires and expressions of students. It holds the prestigious title of Australia’s oldest literary journal. It published a mixture of fiction and non-fiction, poetry and prose, and cultural commentary written by students, for students. For Alwyn, and presumably for many others, it offered a space where ideas could be debated, and students could gain exposure for their writing. Unfortunately, it was shut down in 1969, potentially due to a perceived oversaturation of university publications with the advent of Honi Soit, The Union Recorder and ARNA. Or maybe it was shut down due to conflict over the direction of the magazine. The editor’s foreword of the 1969 edition, declares that the magazine would no longer “be literary in content” as that would be “fairly irrelevant to Sydney University in 1969.” It was resurrected in 1985, before morphing into a literary award for the union — now the University Student Union (USU) — and then officially died around 2020. PULP is now the USU’s sole arts publication.

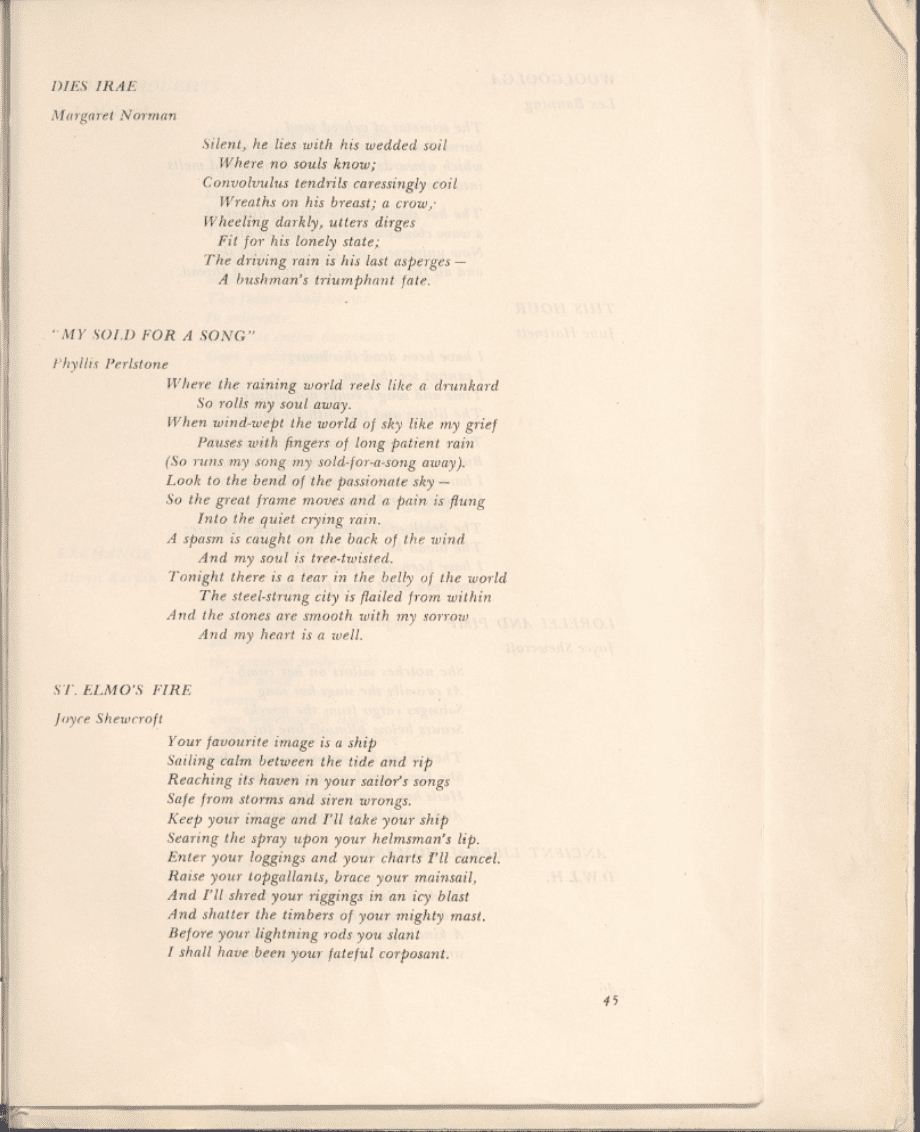

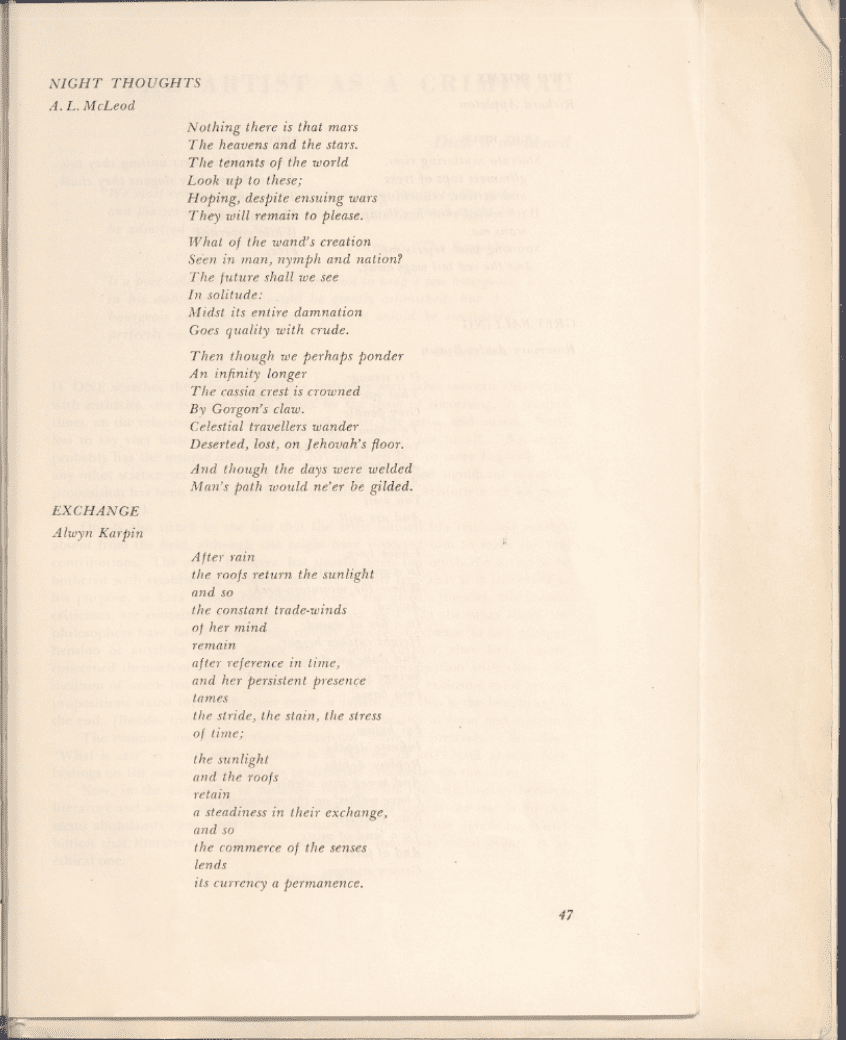

Reading her first issue of Hermes, Phyllis was struck by ‘For the Six Million.’ “I was incredibly attracted to the skill and movingness of his words,” she remarks, “his ability to capture a feeling that I too had grappled with.” Phyllis, also of Eastern European Jewish descent, found the experience of the war a similarly contradictory experience, feeling like an outsider and an insider at once. After reading the poem, Phyllis bumped into Alwyn somewhere in the quad, at a meeting for a left-wing student group, The Push, although she doesn’t recall being too involved in that. She recalls talking to Alwyn about his poem and that they bonded over a mutual love of poetry. I suppose one thing led to another? She is 90 now, so the in-between is not easy to recall. I do know however, that in a perfect sort of symmetry, they both published poems in the 1951 edition of Hermes. Phyllis wrote ‘My Song Sold for A Song’ depicting the aftermath of war on the natural environment. Alwyn wrote ‘Exchange’ which is most likely about Phyllis.

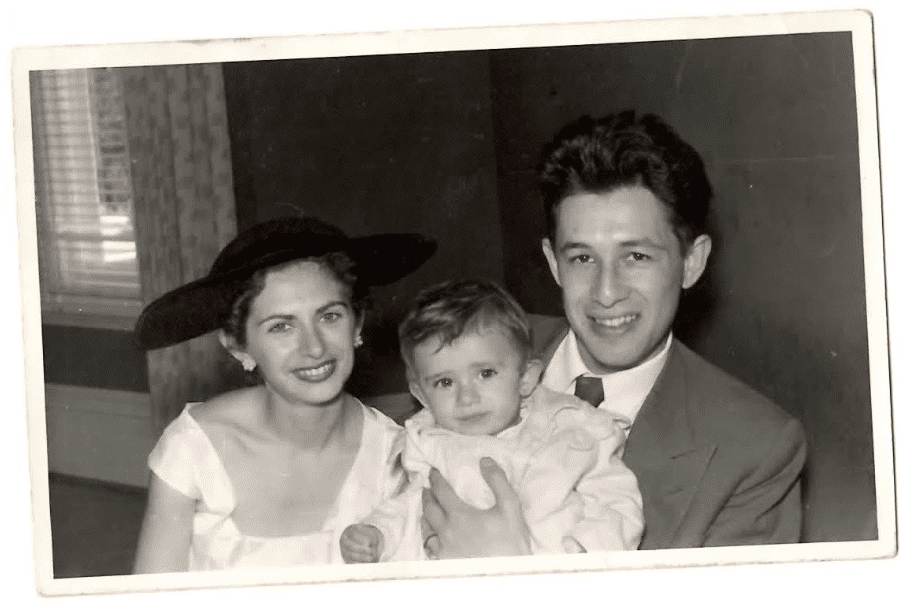

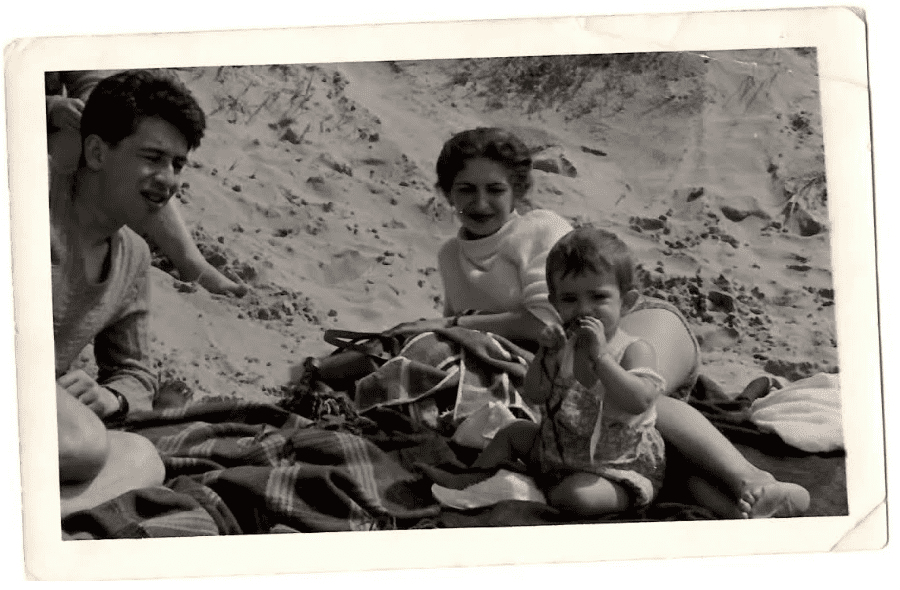

That same year, they got married, and Phyllis found out she was pregnant. She was 19 now and made the decision to drop out of her degree. A life of domesticity and motherhood was looking straight at her, and she was not ready to accept it. She got an abortion and took a job at David Jones where she is swiftly fired when they learn she is married. I asked her why she dropped out of university and she found it hard to explain, returning to that feeling of outsider-ness. “I made a connection with Alwyn that I didn’t have with anyone or anything else and so there was really nothing to hold on to.” Eventually, she and Alwyn did start a family and Phyllis attempted to perform the role of a domestic wife. “I was never very good at it because I found housework extraordinarily difficult,” she tells me. She turned away from poetry. After 19 years together, and four kids later, they broke up, re-partnered and Phyllis returned to university to complete her degree.

Both my grandparents, Alwyn and Phyllis, wrote poetry for their whole lives. Alwyn continued to write, affected by his loved ones and occurrences around him, until he died in 2020. Phyllis writes to this day, and at time of writing has written and published five books of poetry. This story advocates the cosmic power that transpires when poetry, love and print media intersect. Alwyn didn’t write his poem for Phyllis, but in some ways he did, because he found a receptive reader in her. Poetry has this capacity to describe the contradictory impulses and parts of our identity that don’t make sense, and publications like Hermes enable students to hear that from each other, where otherwise they may not.

Thank you to Marlow Hurst for contributing information about the history of Hermes.

Poems by Alwyn and Phyllis