It’s February 2018 and I’m lying on a hospital bed. The anxiety-induced sweat underneath me is soaking the hospital bed linen. An anaesthetist is returning in five minutes to put me under, but at this point I’m having trouble lying still. I pick at my fingernails in an attempt to avoid clenching my jaw. I can hear the clock ticking over. Outside my curtained room, I can also hear a series of murmured voices. “I’ve read about it in the media I think,” says one nurse to another. “Yeah, I always forget the name, but they say it’s a pretty common chronic condition.”

“Should be an interesting surgery.”

My cheeks are now crimson as I lie there, suddenly feeling like an animal up for auction at the county fair… or maybe just a woman with endometriosis.

My surgery, a laparoscopy, will give me a definite diagnosis on a condition that even nurses “forget the name of.” The chronic pain I’ve experienced since the age of 12 will be recognised as legitimate, with a legitimate cause. Perhaps it really is not just occurring “in my head.” Even so, I have to recognise that this surgery may not cure me of any of my symptoms, and the endometriosis could grow back.

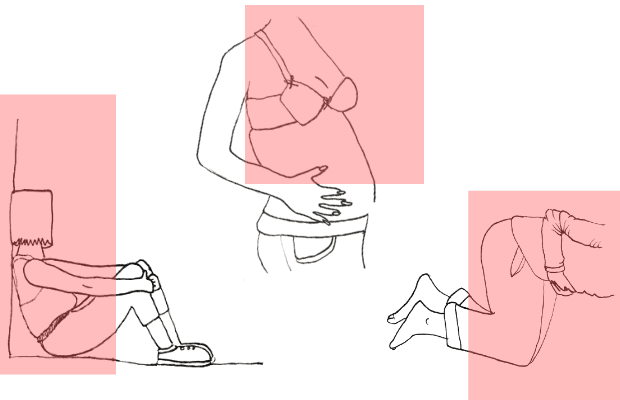

Endometriosis is a disease where tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows in other parts of the body, usually around the pelvis and sometimes in organs and tissues outside the pelvic region. The condition is common, experienced by 1 in every 10 wom*n. It causes chronic pain, affecting basically every aspect of daily life. It has significant social and mental impacts on sufferers, yet it is “invisible” in most social contexts. People who have experienced this overwhelming pain from their very first menstrual cycle wait on average 7 to 12 years for their diagnosis.

176 million people worldwide are affected by endometriosis. It’s been named as one of the top 20 most debilitating and painful conditions by the UK National Health Service. In Australia, 1 in 10 young wom*n suffer from endometriosis, and the research has shown that symptoms can be so severe that schooling, career and social participation is significantly compromised. Donna Ciccia, the Director and Co-founder of Endometriosis Australia, claims that the condition adds a “debilitating layer to already present societal prejudice that prevents wom*n from reaching their potential.”

Wom*n have been taught from a young age to think that painful periods are normal. That having to miss school or work because of overwhelming pain is just part of a normal cycle. The healthcare industry has been incredibly reluctant to explore our symptoms or even give our condition a name — thus many medical professionals are unable to help us. In these circumstances, we are taught from a young age to ignore our menstrual cycles.

The Cell and Reproductive Biology Laboratory run by Dr Laura Lindsay and Professor Chris Murphy in the Anderson Stuart Building works specifically on female reproductive biology. One of the clinical diseases that they’re particularly interested in is endometriosis. Dr Lindsay describes the condition as, “years and years of pain, bleeding and infertility.”

“The pain is often debilitating,” adds Professor Murphy, “but often not debilitating enough that the patient will actually go to see a doctor. They’ll go when the pain is essentially unbearable.”

Still Waiting for Diagnosis

“There are different kinds of pain,” says Isabelle Hans Rosenbaum, a 21-year-old fashion student. “I think the worst one is this electrifying, shocking feeling. It feels like you’re being zapped in your lower abdomen.” She pushes her finger into her stomach, mimicking the jolt. “The other feeling is a bit more dull. The best way to describe it is probably like someone getting a blunt knife and dragging it very deep into your stomach.”

Isabelle has suffered pain from the age of 16. She was originally told by doctors that the sensations were caused by cysts inside her abdomen. There’s not much we can do, they had said. Lots of people have them. She had recurring episodes during which her “cysts” were just “playing up.”

When she turned 18 and her periods became more regular, the pain grew much worse. “I was encouraged to see a specialist,” she says. “The waiting list for this specialist was over four months, and once I did see her, it took another three months to get on a waiting list for surgery.” Isabelle has been on this surgery waiting list for a year and a half. “I get my surgery next month, hopefully.”

Societal ignorance of endometriosis amongst young people has a massive psychological effect on those coming to terms with their condition. On student campuses, this invisibility is further heightened. Students are rushed from class to class, and there’s little connection with individual lecturers or tutors, and therefore a detachment from any understanding of the help that students need. Many students avoid listing endometriosis as a reason for special considerations out of fear of being rejected a few days before the due date. The condition is “particularly undiagnosed in young people because the most common way it is found is through infertility,” said Professor Chris Murphy. “If someone isn’t trying to get pregnant then they just think they feel sick. They don’t consider it to be any more serious than that.”

Lack of knowledge about the condition also makes it difficult to explain one’s emotional, physical and mental state to peers and relatives. This makes young people feel socially isolated. “It’s all hidden pain that can’t be seen most of the time, so you kind of live with most of it alone,” says Lucy Ferris, a textiles student at the University of Technology. “Because it’s an invisible pain, I also find myself thinking that people don’t believe me. Throughout the years of diagnosis, I kept thinking that they would find nothing, and that I was making it up.”

The Social Network

There’s often more community support for endometriosis sufferers online than can be found in a medical centre. The Facebook group “Endometriosis support group” has over 20,000 members, and that’s only within Australia. For young people still looking for a break from the taboo associated with wom*n’s health, this platform is crucial. Posts are frequent, with about 20 to 30 being made per day. There are requests for support, questions about pain relief, diet, mental health, and more. Even patients that suffer from similar “invisible” conditions such as adenomyosis are willing to join endometriosis support groups just to feel connected to those with a similar kind of pain.

“People can just offload some of their pain, or ask for help or guidance. I’ve actually found most of my solutions through the incredible wom*n in that group. I even DM some for help,” says Lucy Ferris.

The positive mental impact that the group brings for sufferers is immense. It’s a confirmation that they’re not alone, and that extreme “period pain” is not normal, no matter how many people brush it off as such. “I feel like these support groups where I can get advice and talk to people with the condition have helped me more than doctors have. I’ve spoken to so many people about this and they’ve said the same thing,” says Isabelle Hans Rosenbaum.

These online platforms are particularly valuable for Australian endometriosis sufferers who live in rural or remote communities, where wom*n’s healthcare in general is lax. In addition, the sites are open to the families of sufferers as well, allowing them to increase their understanding of the illness.

Genes of Infertility

It took Nell’s mother up to ten years to fall pregnant with her. Years of trying, an unimaginable series of tests, appointments, IVF treatments and miscarriages led to a particularly late — but not abnormal — diagnosis of endometriosis at the age of 35. There was a very slim chance of having children. But when she was well into the process of adopting a child, she discovered that she was having Nell.

There’s so little known about the cause and symptoms of the disease that when one is finally recognised as a sufferer of endo, there can be very little time to decide whether they want children, especially as 1 in 3 people with endometriosis have problems with fertility. The only way to confirm if someone has endometriosis is through invasive surgery. Because of this, early diagnosis is almost impossible. Although not confirmed, it appears very likely that endometriosis has a genetic component. As a result, sufferers experience recurrent anxiety about passing the disease onto their children. Further research into the disease will give wom*n the opportunity to prepare for their future. “As a wom*n, if you knew you had an illness that may affect your fertility, you may weigh up the choices differently,” says Dr Laura Lindsay. “If you knew you had endometriosis, you might prepare. We know from studies that if you get into the IVF clinic before the age of 35 you have a better chance of pregnancy and successful birth.”

Money where the uterus is

Although endometriosis is as common as asthma and diabetes in Australia, it receives less than 1 per cent of research funding. When looking at how wom*n’s health has been ignored throughout history, it becomes clear that the disparity in the distribution of financial resources occurs on a gendered basis.“If men had painful sex, painful defecation and painful urination, the entire US defence budget would be spent on finding a cure,” Ciccia says, quoting Nancy Peterson a Endometriosis Advocate USA.

Change could be in the air. In 2018, Australia brought about its first National Action Plan for endometriosis, which provided upwards of $2.5 million to the cause. The Plan directly apologised for ignoring the health of young people with endometriosis, and promised to improve awareness as well as clinical management and care in Australia. The Plan also has a particular focus on increasing education for young people about endometriosis through updating school curriculums, and teaching students and staff about the signs of irregular menstrual health and their options for support. Donna knows that change will come from heightened awareness. “I can get in a cab with a 70-year-old taxi driver and make sure he knows all about endometriosis by the time I get out,” she said. It’s about recognising the conversation as not only normal, but also crucial.

BREAKING: Yet another study done on how wom*n’s health issues affect men

In 2017, a philosophy research student at the University of Sydney began a study on the sexual impact of endometriosis on men who have partners with the disease. I raised this study with Chris and Laura.

“I don’t think that study would show up on my basic science flag,” says Dr Lindsay.

“I can imagine that a study saying that endometriosis has affected the sex life of men could have been a bit controversial and perhaps in poor taste,” Dr Murphy adds.

This study, both sexist and under-researched, was also majorly premature. Endometriosis does not have a known cause, identification or treatment, and would benefit from further research into its own genetic links and related conditions — not a major study focusing on how the condition affects other people. Wom*n are often conditioned to accept pain quietly. When offered treatment, regardless of its severity, they tend to accept these treatments on the basis of pure desperation. “Women will accept a hysterectomy for the vague chance that there may be a reduction in symptoms, and we know it is definitely not a cure ” said Donna Ciccia.

The Inconvenient Pain

Dating in your late teens and early twenties is difficult enough as it is. In a social landscape that from an early age de-legitimises the pleasures and needs of wom*n and non-binary people during sex, it is already difficult to find understanding and support from partners. Casual dating sites and applications obscure and misinterpret the needs of young people suffering endometriosis because of their focus on physical and snappy connections. In casual relationships, sex is treated as a quick fix. So when conversations arise about pain and discomfort during sex as a result of endometriosis, young people can be left feeling embarrassed, misinterpreted or ignored.

“With dating, I find it can be a nightmare sometimes. I’m currently single, and just find myself giving up sometimes on meeting new people,” says Lucy. “Because the pain is pretty much always there to some degree, it’s hard to go on a date and be like ‘hey, so I feel like absolute shit but I gotta just smile through this and just wait for it to be over’.”

Social and physical discomfort is only part of the problem for young people balancing endometriosis and their personal relationships. “I get really down on my body because of all the bloating and stuff, so going on a date and feeling confident is just so rare,” says Lucy. “I end relationships pretty quickly because I just don’t want to deal with all the physical and emotional pain that is tied to my endo.”

I’ve had sexual partners who have told me that it’s completely normal for wom*n to experience painful sex and I was basically expected to lie back and think of England. Before my surgery especially, endometriosis had a massive negative impact on my sexuality. I started to blame myself and told myself I was making a big deal of nothing, even though I couldn’t walk for days after sex due to the pain.

“There’s so much that’s not known,” says Dr Lindsay. “I think we need to push that yes, we need clinical research, but we need basic scientific research first to understand how the disease develops, and then a diagnostic test. Researchers need to figure out how we can get a diagnosis and how we can give wom*n information so that when they’re in their early 20s, they can understand and decide what to do?”

With endometriosis, it is difficult to find a partner and a social network with compassion and understanding for your symptoms. There’s a pressure to constantly stand up for yourself, or to be the explainer or advocate for the disease to others who don’t understand. That pressure can be exhausting, especially when research into the disease is speculative and ongoing.

Developed research in endometriosis causation and treatment is sluggish and frustrating for its sufferers. For a disease that simultaneously pushes you into the spotlight as ‘advocate’ and confines you in an often invisible bubble as ‘sufferer,’ it’s enough to make young people feel trapped under a microscope. For now, endometriosis sufferers find support in each other. Perhaps soon, this “fairly common condition” may be given the wider attention it deserves.