William Wright: Yes

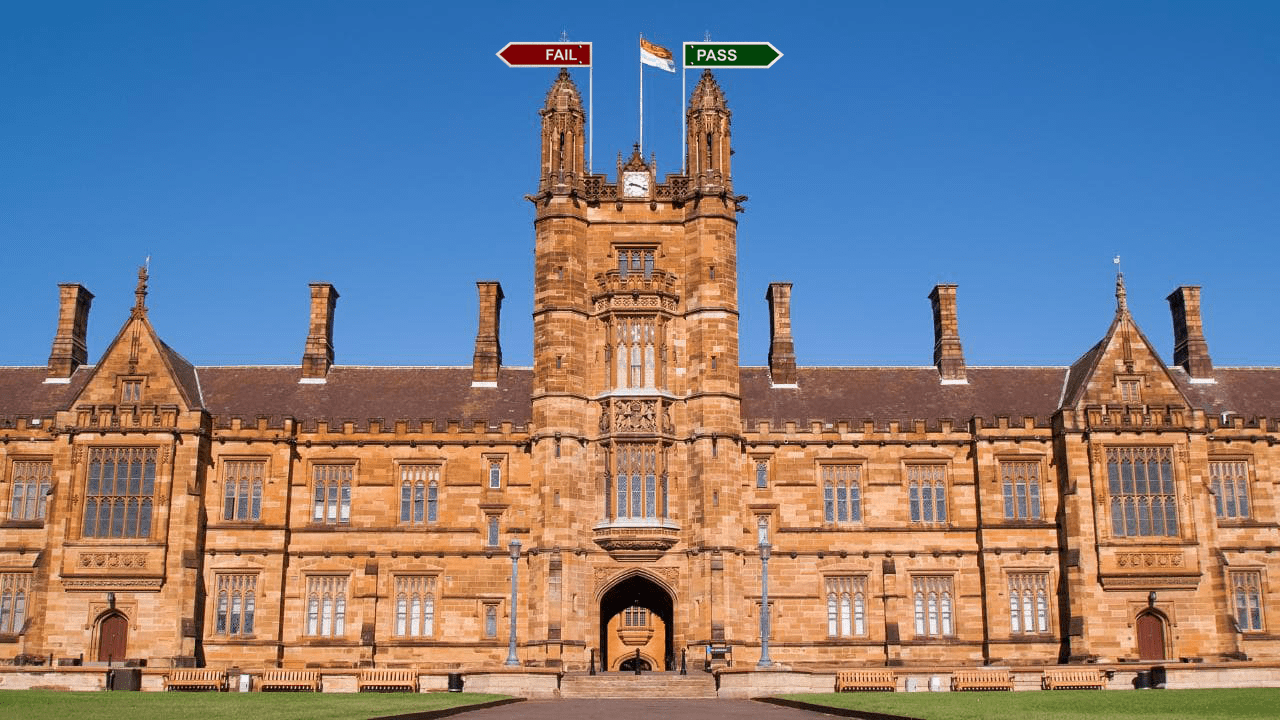

3,900 is not a small number. It makes up almost 12% of the USyd undergraduate population, and it is an unambiguous mandate for a pass/fail grading system to be implemented this semester at USyd.

In the past 72 hours, 3,900 people have signed our petition demanding the Vice-Chancellor move to a pass/fail system for grading given the unprecedented circumstances being experienced by all USyd stakeholders during COVID-19.

The need is clear: a fair and reliable method of learning and assessment cannot be maintained without a pass/fail system.

Online learning is an inadequate substitute for our regular system of learning. It unfairly disadvantages kinaesthetic learners, giving an advantage to visual and auditory learners. For domestic students, the instability of the NBN makes meaningful engagement with complex course content nearly impossible. Patchy connections, feedback loops, echoes and other issues arise from using applications such as Zoom.

The inadequacies in the current USyd system of online learning makes the playing field uneven. Those from more affluent backgrounds will be able to gain better access to the online learning environment, whether that be a result of a better internet connection, better living conditions, no need to look for new jobs, no need to care for others, etc. Better access means better information, and that usually means better grades. That is not how university is supposed to work. This is not to mention those in regional/rural areas or international students who have to deal with the unreliability of VPN’s.

And many of us still face the prospect of ProctorU supervised online exams. This is reasonably causing widespread consternation as a result of its apparent invasion of privacy. I will not go into it further in this article, but an online search yields troubling results.

USyd prides itself on being ranked amongst the best universities in the world. While I do not advocate that we simply follow what others are doing, the fact that universities such as Harvard, Stanford and Columbia have moved to a pass/fail system is telling. For students of those universities, as of ours, the threat of poor or atypical grade performance is a real one for future job prospects. This should be the last worry in the minds of students who face the challenges of finding substitute employment, housing or even meals during this difficult and unprecedented period.

The main criticism of our proposal has apparently come from Honours students or those who wish to boost their WAM. We should not let the tail wag the dog. A simple and effective method of addressing this issue is to make pass/fail an opt-in system. This will have the effect of addressing the concerns of the student population. At the same time, this will give a reprieve to teachers who are struggling under the current circumstances.

This is not an easy time for any of us: thousands of students have lost casual employment, thousands don’t know where their next rent cheque is coming from, and all of us are terrified for our health and wellbeing. The last thing we need to worry about is our grades. It is now more than ever that we need our University to support us. This is a semester unprecedented in the history of this University, extraordinary times call for extraordinary measures. It’s time to ease the burgeoning stress on our students.

We ask the Vice-Chancellor to please reconsider our proposal. To individual faculties, we ask you to consider this proposal yourselves, like the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at UNSW.

To those who haven’t yet signed the petition, the link is here: Petition · Move to a Pass/Fail grading system for USyd during COVID-19.

Lauren Lancaster: No

This week the UNSW Faculty of Civil and Environmental Engineering became the first Australian university faculty to transition to a coronavirus-prompted pass/fail grading system. On Friday 27 March, the Vice-Chancellor sent a University-wide email clarifying that the University of Sydney would not follow suit.

When multiple Ivy Leagues have taken the same route as UNSW in adopting this system, it raises the question — did Spence make the right call? At least in this instance, it would appear he did.

The case against pass-fail emerges from consideration of the initial goals of the system, it’s devolution to the present day and the implications it would have on future performance and student welfare.

The pass/fail system emerged as a response to the 1960s American college protests, focused not only on civil rights and war but also on a transformation of teaching and learning. As Mario Savio (of the Berkeley Free Speech Movement) stated in 1964, universities had become ‘machines’ and students ‘bodies upon the gears’ – capitalist servants rather than emboldened thinkers capable of moral and intellectual revolt.

The pass/fail system allowed students to explore subjects outside their core degree without fear of a GPA drop. The scientists could take a poetry course, and the poets could venture into physics. However, by the 70s the pass/fail system became corrupted and students used it to game university, to achieve their degree with the minimum amount of work.

That’s the situation we find ourselves in now – pass/fail grading is a numbing exercise that will demotivate students and leave those struggling even further behind. It is not an appropriate remedy to the distress and displacement caused by COVID-19.

Psychologists Richard Ryan and Edward Deci’s theory of self-determination helps explain why the pass/fail system is problematic. The two of the pillars of the theory are purpose and mastery: purpose is the intrinsic or extrinsic shaping of our need to do something, while mastery is the autonomous pursuit of a greater understanding of that which gives us purpose.

A student’s purpose is to, simplistically, do well in their subjects so that they can achieve their degree. Achievement of purpose is quantified using the metric of marks. The grading system allows progress to be tracked and future study optimised — committing to a goal for an assessment is a simple and effective way to push ourselves to achieve, even if we may fall short.

Abolishing a nuanced grading system in favour of a pass/fail system diminishes purpose. This in turn impacts directly on the pursuit of mastery. It does not incentivise a student to seek to excel. And by the same token, it demotivates more able students — why would you try hard in a subject if you will be lumped in with 50% of your cohort who do not necessarily share your passion for it?

In such bizarre times, it is a small but meaningful comfort to have a number motivating you to roll out of bed and do something other than disappear into a black hole of existential dread and three-day-old hot cross buns.

Marks are also necessary for scholarship students, honours courses or transfers that require WAMs and achievement details to maintain high-quality programs. Even if there are exclusions that protect these students, the discretion should be in the hands of students as to whether they receive a mark for each unit, or opt for pass-fail. Autonomy is key and far preferable to a blanket decision made in the shadowy halls of the University administration.

Further, a pass/fail system is just another way for universities to absolve themselves of responsibility for student welfare. Changing the grading system does nothing to meaningfully assist students struggling with at-home study, online assessment or the drastic loss of connection to friends and family. Instead, the University must fund better student support services (Student Centre wait times, looking at you), remove barriers to special consideration and increase mental health service support.

Should Spence revisit the University’s decision, it should only be with optional pass/fail in mind. However, we must not overhaul our grading system prematurely in reaction to a pandemic that will end.

Stay positive, stay connected and we will get through this!