This article discusses rape and sexual assault.

This week, Australia learned about another woman’s fight to speak out about her sexual assault. Sandra* shared her story with journalist and director of End Rape on Campus Australia (EROCA) Nina Funnell, who last year created the #LetHerSpeak campaign in partnership with Marque Lawyers. Sandra is now following in the footsteps of Grace Tame and Tameka Ridgeway, who both won their right to tell their stories in the media using their full names through the Tasmanian High Court last year. Archaic gag laws in the Northern Territory currently prevent her from doing so but they are coming under attack again, and rightly so.

Sandra is a nursing student from Darwin. She has been through an ordeal to get to this point. In 2017, she was raped at a buck’s party by an attendee while she was working as an adult entertainer. She reported her rape to the police, and they charged the offender but it wasn’t until two trials later – the first resulted in a hung jury – that she finally got justice. Her rapist was found to be guilty and was sentenced to three and a half years in jail but was suspended after nine months.

Because of the sexual assault gag laws that still exist in the Northern Territory, any journalist that spoke out and named Sandra even with her permission would face six months gaol time. So would she.

This law that still exists in the Northern Territory is outdated and offensive. It’s a law that benefits perpetrators and harms victims, who are not able to tell their stories or humanise themselves in any way. The public is always suspicious of people who speak to the media anonymously; when you can’t put a name or face to the story, it’s easier to doubt it, to make nasty comments, to humanise the perpetrator instead, who has the power to do interviews and control the narrative. At the time, local media called her rapist a ‘larrikin’ and a ‘family man’ while she was referred to as nothing more than a stripper.

Sandra must know the potential for further public backlash because of her profession and because of the misogynistic, victim-blaming attitudes that are rampant in Australia. That she wants to do it anyway is indicative of the importance of this issue to her, and of the strength and resilience of her character. For Sandra, the benefits of speaking publicly far outweigh the personal cost.

Sandra wants to be able to speak publicly for two main reasons. Firstly, she wants to educate women – and especially women like herself – about their rights in the adult entertainment industry and more broadly. Secondly, she wants to lead the charge in combating victim-blaming attitudes across Australia. Neither of these are easy tasks, but they’re essential in protecting women and creating real change.

Sandra is by no means alone and is not the only woman who suffers the consequences of these outdated laws. The Northern Territory has the highest rate of sexual assault per capita in the country, and police in the Northern Territory are less likely to pursue a sexual assault report than police in any other state or territory in Australia. The laws there systematically gag survivors en masse, to the point where it is not even possible to engage in public discourse about the issue.

This law is more dangerous again because it silences Aboriginal women, who make up over 50% of women in the Northern Territory that have faced sexual assault and harassment. It’s impossible to emphasise how problematic this is; the gag law perpetuates a systematic inequality that allows external bodies to speak on behalf of Indigenous people and permits them no autonomy to tell their own stories.

However, both Tasmania and the Northern Territory, the last two states to have these archaic laws, are in the process of doing something about it. Last week, Tasmanian Attorney-General Elise Archer introduced a bill to reform the archaic gag laws of section 194K of the Evidence Act. This reform would allow sexual assault survivors to speak publicly about their assault if they are over eighteen and provide consent to being named in paper. The catch, however, is that survivors still cannot be named until all other possible avenues of appeal have been exhausted following the conviction, which could take years, and which still allows the defendant to speak publicly and control the narrative throughout the proceedings while silencing the victim.

In the Northern Territory, the process has just begun. The government is calling for submissions from the public about the change of legislation. But survivors in the Northern Territory will face the same problem as in Tasmania. They would only be able to speak once all other avenues of appeal have been exhausted.

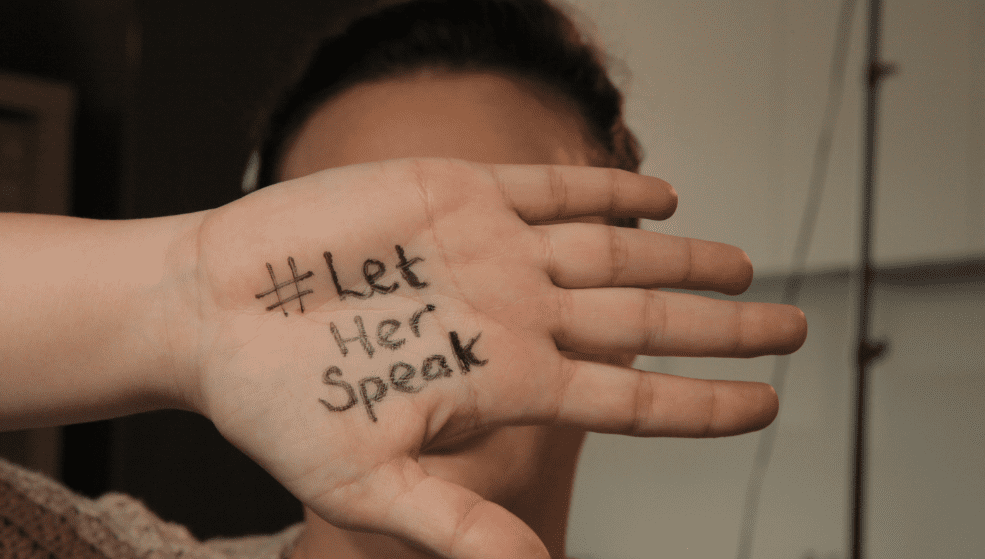

The #LetHerSpeak campaign took off last year when Grace Tame won the right to tell her story. It’s such an important campaign because it’s a way to support survivors while spreading the movement to change the laws. The fact that these laws still exist says something about Australia as a country. The fact that women in New South Wales are not impacted by it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be joining the fight. In fact, we should be at the forefront of it, because we do have the right to speak and we can take some of the burden on our shoulders.

The best way to support Sandra is to take a selfie and upload it to social media with the hashtag #LetHerSpeak.

Sandra* is the name which this woman is using to tell her story.

If you or someone you know has been impacted by sexual violence support is available by calling 1800 RESPECT on 1800 737 732.