For forty-seven months out of every forty-eight, women’s artistic gymnastics (WAG) is among the least followed of all sports, save for the small but passionate “Gymternet”. For one month every four years though, when the Olympic Games come along, its popularity fleetingly surges. The Gymternet has a pejorative epithet for this surge – four year fans. I’ll confess that, in 2016, I was a four year fan who didn’t know a Shaposhnikova transition from an Amanar vault. This year I’d hoped to shed my four year fan status, proudly demystifying the intricacies of pirouette angles and toe point for my less initiated friends.

Women’s gymnastics is a sport full of ironies and incongruences. Historically, its breakout stars have been short teenage girls in sparkly leotards and scrunchies made to perform gruelling feats of athleticism to upbeat instrumental music. While their male counterparts can compete in silence and are permitted to show the full effort of their athletic feats in their faces, female gymnasts must not only stick the landing, but smile as they do so.

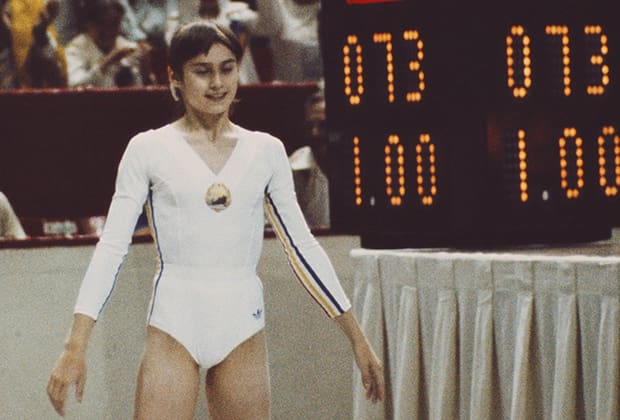

The most famous athlete in WAG history is undoubtedly Romania’s Nadia Comăneci who, at 14, floated effortlessly between the uneven parallel bars and earned the sport’s first “perfect 10” at the 1976 Montreal Olympics. The famous photo of teenage Comăneci, 4’11”, standing next to a scoreboard reading “1.00” (the scoreboards were not appropriately programmed to show 10) is still one of the most iconic and well remembered moments in Olympic history.

Since the late 1970s, however, the sport has transformed irrevocably. The perfect 10 is no more. Since 2006, gymnasts have received an open-ended difficulty or “D” score and a 10 point execution or “E” score. A controversial system with both supporters and detractors, the open-ended code was introduced to promote skill innovation and originality of routine composition. While some feared that gymnasts would win by compromising execution for acrobatic difficulty, the first Olympic all-around champion in the open era (at the 2008 Beijing Olympics) was Nastia Liukin, a Russian-American born to Soviet gymnastics royalty. Liukin, a gymnast excelling in execution on the balance beam and uneven bars, edged out her more acrobatically powerful fellow American Shawn Johnson. During her career and especially after her all-around victory, she was praised for her “elegance”, “lines” and “international look” – more often than not coded language intended to insidiously describe that she was leaner, taller and more Eastern European than Johnson.

None of this is to say that Liukin’s victory was not well deserved. But in time, the arc of gymnastics has bent further towards powerful acrobatic gymnasts like Johnson. Eastern Europe’s once famed WAG programs have fallen away. Romania, once a formidable power, failed to even qualify a team to the last Olympic Games. While Russia remains a medal threat, the US have won team gold by unprecedented margins at every major international meet since 2011, and remain the prohibitive favourites whenever the next Olympics occur. While a vocal minority of the Gymternet lament the bygone era of balletic gymnastics, many celebrate the new era’s emphasis on sustainable training (including conditioning) and healthier athletes capable of the intense acrobatic demands of the sport.

Despite the wholesale athletic transformation of WAG, the gendered expectations of performance and presentation remain. Age too is an apparently granite barrier. Although event specialist gymnasts have begun to regularly compete into their late twenties, there have been fewer meaningful shifts in the all-around (AA) event, which combines scores from all four apparatuses (the floor exercise, vault, balance beam and uneven parallel bars). Only one winner of the Olympic AA event has been out of her teenage years in almost half a century. No woman has repeated an Olympic AA gold since the 1960s, in the now unrecognisable “classical era” of WAG, and the feat had been thought functionally impossible.

Until Simone Biles.

Biles is the reigning 2016 Olympic champion in the AA and on the floor exercise and vault. If the open-ended era of gymnastics were to have a true protagonist, she is undoubtedly it. Despite performing the most difficult routines in history, her execution scores have been superior to gymnasts with far easier routines. Biles, a short and muscular African-American woman, is usually described as powerful rather than elegant, even as she perfectly executes complex flexibility skills.

In 2013 after Biles’ first world AA victory, an Italian gymnast claimed that “[Italians] should also paint our skin black, so then we could win too”: a plainly racist comment disguised as commentary on the athletics trend in gymnastics. The year before, Gabrielle Douglas, another African-American woman, had narrowly edged out a popular Russian gymnast to win the Olympic AA title. Racists feared Biles’ 2013 victory was a confirmation that “elegant” white Eastern European gymnasts could never win again. In the next three years, Biles became unstoppable. After winning the Olympic AA at 19, she could very well have ended her career and taken a place next to all-time greats like Comăneci. For a while, she seemed to be doing just that, not competing or training at all in 2017 and appearing on Dancing with the Stars.

Then, at the very end of 2017, she began a comeback, expecting to return to international competition in 2019. Returning to elite gymnastics after a lengthy hiatus is historically complicated. When Liukin attempted to return in 2012, she failed to make the Olympic team and ended her career, quite literally, on her face. For Biles, returning to gymnastics was particularly complicated by the new revelation that she had survived sexual abuse enabled by the sport’s national governing body, USA Gymnastics. And yet, Biles returned to elite competition earlier than anticipated, performing harder skills than the unprecedented ones she’d performed in 2016. With a kidney stone, a broken toe and two falls at the 2018 world championships, Biles still won.

While in her early career she had manifested the kind of punitive humility expected of elite female athletes, her comeback showed obvious signs of change. A woman in her twenties, she had become something of an elder stateswoman in a national team still filled with teenage girls, a fierce advocate for sexual abuse victims and the harshest critic of the unyielding toxic culture in the US gymnastics federation. In 2019, when she arrived at US national championships with a bedazzled goat on the back of her leotard – a reference to her undisputed status as the greatest of all time (GOAT) – she expressed a confidence seldom seen from archetypal teenage gymnasts. At the same competition, Biles unveiled the two hardest skills in women’s gymnastics history. Even the sexist gymnastics commentariat found it improper to label her arrogant. A year from her second Olympics, she seemed to be on the precipice of breaking generations-old glass ceilings.

Even before the Olympic Games were postponed, Biles was making no secret of her (and her bodies’) desire to retire immediately after her final floor routine in Tokyo. Throughout her comeback, she has lamented performing for a gymnastics federation that enabled her abusers. Although Biles, now 23, is nominally all in for next year’s Olympics, her retirement before 2021 seemed entirely possible. If (to the Gymternet, more like when) Biles repeats as the AA champion next year, she’ll be the oldest woman to win that title in over half a century.

It may be decades before we see another athlete, let alone gymnast, quite as dominant as Simone Biles. But perhaps what is most remarkable about Biles’ storied career is not her thirty world or Olympic medals, four eponymous skills or the countless records she has left in her wake, but the extent to which she has singlehandedly remodelled her sport’s sexist and racist norms.

It is for that reason that we, four year fans and Gymternet faithfuls alike, should culturally archive the gymnastics of Nadia Comăneci. While Comăneci will forever remain a legendary and beloved Olympic athlete, next year, four year fans will be captivated by an entirely different sport. They will watch a sport of powerful, diverse adult women that push the limits of athletic possibility. They will watch Simone Biles’ sport.