Based on Sally Rooney’s bestselling novel, Normal People follows the relationship between Connell and Marianne as they navigate the end of high school and their years at university at Trinity College in Dublin. It’s interesting how a story about a young, white, heterosexual couple in an on/off relationship feels so fresh and resonant, and has been so universally acclaimed and related to. Personally I was surprisingly moved reading the novel, which is written in self-reflexive and accessible language. What makes the conventional plot so unconventionally stirring when told by Rooney? The show reveals, perhaps more overtly than the book, that it is the up-closeness and intense vulnerability with which we experience Connell and Marianne’s lives and how they tangle together that makes it impossible to untangle ourselves.

The show has an understated, quiet and raw tone, palpable most clearly in its multiple sex scenes. The first sex scene was so realistic and intimate that I felt like I was intruding, like I shouldn’t be in the room. The trusting performances of the two stars, often in natural light, the absence of music and the sound of every little breath rendered the scenes less gratuitous than their length and graphic nature might otherwise be. Whether tender or compromising, each scene was clearly trying to evoke meaning regarding the emotional intimacy of the respective characters, rather than constructing an object of desire.

The book itself is dialogue-heavy. Much of this is directly transported to the screen, likely thanks to the fact Rooney herself was one of the screenwriters. The show reflects the book’s form of being structured in discrete scenes, and conversations are portrayed in a way that leaves space for reflection on everything that is said, or not said. The deployment of silence in conversations in perpetual close-up, the frankness of the subject matter, the lingering of the camera after a touch or a glance render every moment ripe for analysis, for both the viewer and the characters. Marianne and Connell exist in their own universe, infinite not only in depth, but in smallness.

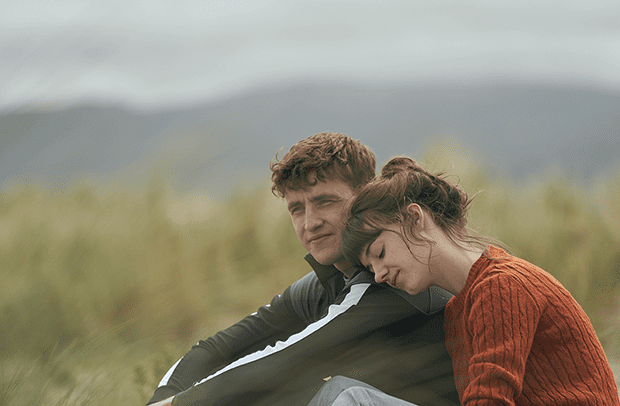

At first, you squirm in the spaces between words – especially Marianne’s – the kind that you’d think but probably never say. It feels as if words are only ever placed into a silence between them. Everything is deliberate. Good sound quality means even the hesitative noises Connell makes are picked up. Words are placed precisely, like notes on a stave. Some lines are like shards of porcelain: cold, precious, broken. These scenes illustrate the subtle performances of (the potentially too attractive) Daisy Edgar-Jones and Paul Mescal and their easy chemistry.

Some of the shifts between gaps in time are not so gradual – the most jarring contrast being the shift in Marianne’s social standing between high school and her first year at Trinity. But perhaps this shift emphasises that how we relate to people is so often based on how others in that shared space relate to them. The show’s momentum is largely sustained by the sexual tension between Marianne and Connell. As the show darkens, their relationship becomes more complex and they individually suffer through toxic relationships and mental health troubles. The dormancy of the show’s driving force compounded by the confronting subject matter makes it rather hard to watch in parts — it’s much harder to binge than other shows. You’re less likely to race to find out what happens next and instead just sit with the ending of each episode. Like the characters, there are points in the second half of the series where you feel flat. Watching their loneliness intensify whilst apart affirms to us, but often frustratingly not to Marianne and Connell, that it’s just the moments between them that you want.

There is an undercurrent of toxicity that is difficult to reconcile when one considers just how much power they have over each other. It makes the audience feel powerless too. They can only really talk to and understand one another, yet at times they struggle to communicate at all. Cruel whispers echo at the back of their minds that they don’t deserve each other, but that they simultaneously need each other; an idea that is never fully recognised or criticised within the show. The idea that there is only one person who can help you through your depression, or one person who will notice you, or know the real you, is scary and potentially a little dangerous. Yet it’s difficult to delineate between toxicity and notions of a deeper, real, special kind of love. Maybe we just don’t want to admit that we were happier with that person, or that we would be better if we were with someone, or that maybe people can change each other.

As an aside, Rooney, a self-proclaimed Marxist, is often touted as imbuing her fiction with Marxism: Normal People has been described as an exploration of young people navigating romantic relationships within contemporary late capitalism. Conversations with and around Rooney project a more detailed class discourse than is between the lines of the novel, and even less a part of the narrative of the show. Whilst there is a manifest class divide between Connell and Marianne, the class discourse is surface level, gestured to only by a few discussions about finances, scholarships and university conversations demonstrating the cultural capital and currency of smartness.

There is no grand obstacle to Marianne and Connell’s relationship. No third act twist, no necessarily linear narrative and resolution. When they’re finally together, it feels still, like a pond. Every breath they take or word they say is like a ripple in the water. Ripples become waves. And like waves and sand, they withdraw from each other, then are pulled back together over and over again. For a lot of the show I was uncomfortable, and I sense that I was deliberately put in that position. That discomfort is where all that meaning is. Visually confronting these perceivably ‘normal’ struggles, lives and emotions with glaring openness leaves the viewer sometimes feeling too up-close, maybe wanting to cry and simply not being able to look away – like staring directly at the sun.