In light of recent instances of police repression on student protests, Honi Soit asked some activists who have been involved in past movements and protests to see whether their experiences with police have changed or not. Words by Eleanor Morley, Thalia and Dora Anthony, Dr. Rowan Cahill and Shovan Bhattarai.

Eleanor Morley on the Abbott government’s attempts in 2014 to deregulate university fees.

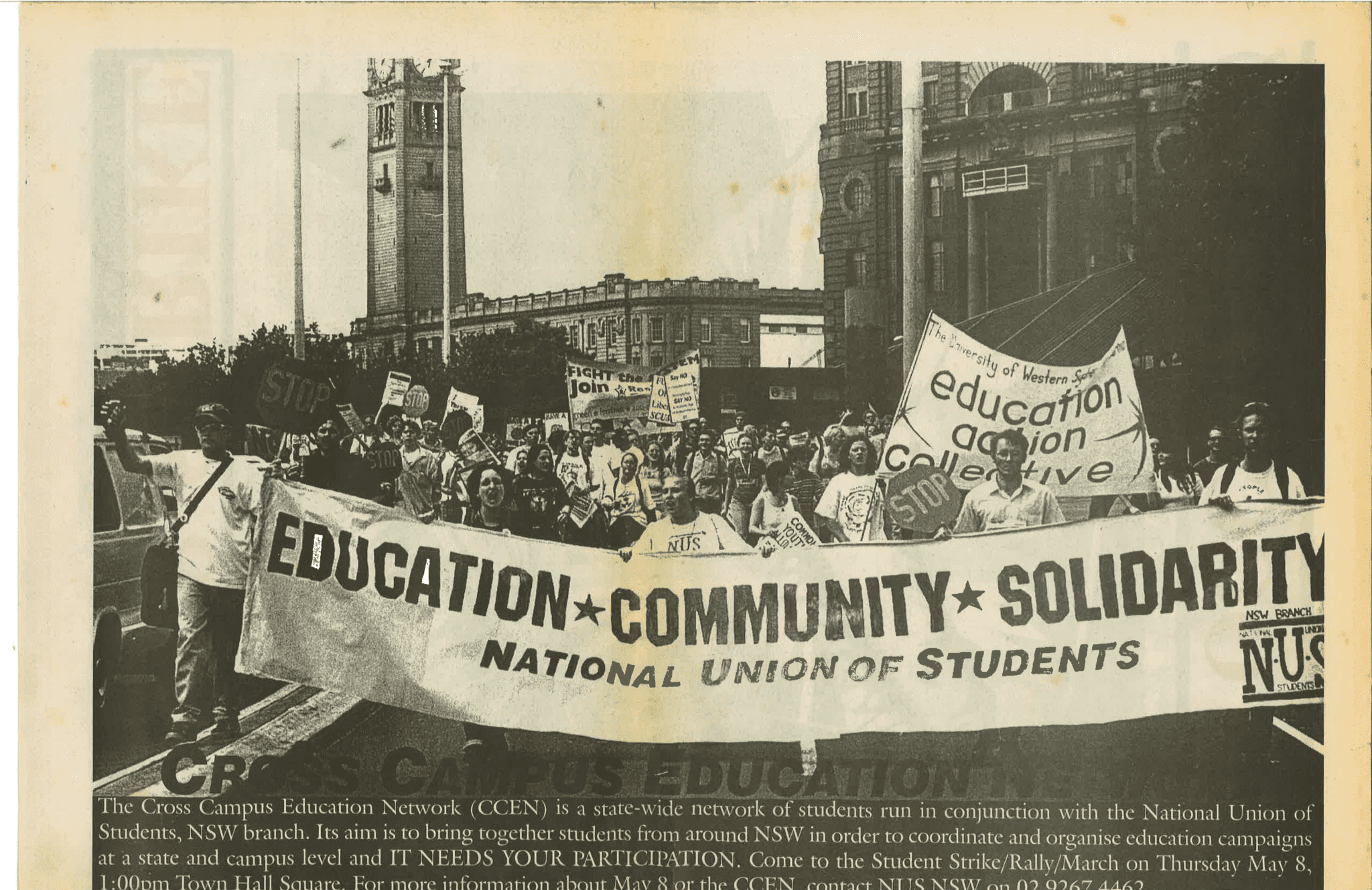

In 2014, the most sustained and successful student campaign in a decade managed to defeat Tony Abbott’s attempt to deregulate university fees. The hated Abbott government handed down a horror budget of sweeping cuts to welfare and the public sector in May, provoking nationwide outrage. Visits to the GP were no longer to be free, the already punitive welfare system was to be made worse, and higher education was in the firing line.

Deregulating university fees was intended as another big step towards a US-style higher education system. Allowing universities to charge whatever they like for each course would lead to an entrenchment of the two-tiered model; the sandstone universities were to become the ivy leagues, and the rest of the sector the community colleges. It was clear at the time that the next step for the federal government would be overhauling the HECS system – which is already deeply flawed – forcing students without wealthy parents to be trapped in a lifetime of debt.

Of all the neoliberal measures in the 2014 budget, fee deregulation quickly became the flashpoint of resistance. This was because the student movement had already started to dust itself off the previous year when the Gillard government tried to cut $2.3 billion out of higher education funding. Education activist collectives had been re-established on campuses across the country, and the left had won considerable influence in the National Union of Students.

These networks quickly moved into gear, organising protests and disruptive stunts in every major city in the weeks following the budget. A diversity of tactics allowed us to bring thousands of students into the campaign, garner considerable media attention, win public sympathy, and eventually defeat the bill.

We crashed Q&A when the hated education minister Christopher Pyne was on the panel. We hounded down Liberal ministers whenever they set foot on our campuses; Pyne announced on national television that he was cancelling a visit to Deakin University for fear of student protesters. We blockaded university senate meetings when they were voting to endorse the bill. But most importantly, we organised nationally coordinated rallies that drew thousands of students – and some parents – into the fight against Abbott.

The campaign was not without controversy. Some student representatives argued our energy should be focused on lobbying the conservative Senate crossbenchers – including mining magnate Clive Palmer. Others said they were tired of rallies and instead wanted to prioritise small actions of a dozen or so people locking themselves on to university buildings. But the mass character of the campaign was decisive. It was a loud and angry visual representation of the mass opposition to fee deregulation amongst the wider student body, and it gave many young people their first taste of political activism.

In the end, our campaign managed to defeat the fee deregulation bill in the Senate – twice. This was the first major victory for a student campaign in almost two decades. Pyne quickly became the most hated senior government minister, and the mass public opposition toward Abbott eventually lost him his job the following year.

2014 was a vindication of the strategy of mass, disruptive protests. We didn’t win by politely asking politicians to support our cause; we won by organising and mobilising a widespread discontent into a powerful and defiant force.

Thalia and Dora Anthony on the UTS tower occupation against the Howard government’s fee hikes and university cuts in 1997.

The UTS occupation was part of a broad campaign opposing the Howard Government’s fee hikes for university students and massive cuts to university funding. Feeding into the government’s agenda, in 1997 university managements were considering the option of up-front fees to supplement university income. UTS was the first university in the country to take decisive action towards introducing full-fee student places when the UTS Council moved a motion to this effect.

The student body chose occupation as the means of dissent, corresponding with actions being pursued across the country in protest against the government’s attack on higher education. Around the same time as the UTS occupation, there were several occupations of the University of Sydney Vice Chancellor’s offices, often ending after a number of hours when police violently entered and removed us, and there were sit-ins at RMIT, Western Sydney University and Wollongong University.

Throughout the occupation, police had under-cover operatives deployed on campus and used phone taps. In one incident, students created a fake protest, talked it up on the phones, sent fake faxes to media outlets, all of which led to scores of police being deployed at site on the other side of the city from where an actual occupation took place. Undercover cops were central to the police strategy at the UTS occupation.

When the police ultimately stormed the occupation, we had been occupying the UTS administration/management block of the Tower for five days. The Tactical Response Group arrived with German Shepherd dogs in the early hours of Sunday morning when about 100 of us were asleep or just waking up. The police intervention came after days of student negotiation with UTS management, yet police did not enter in the spirit of negotiation or de-escalation.

Police forced their way into the occupied area in their dozens. They unleashed German shepherd police dogs on us. Some students were seriously wounded by dog bites. After the initial frenzy, all of the students huddled together in a large circle on the ground floor, with arms firmly linked. Some police officers filmed us and watched from the upper level, others surrounded us, and many more waited for us outside. Police detached one student at a time, using torture techniques such as neck holds and pressure points, and took each student outside. In solidarity with one another, we all resisted when it was our turn at being removed from the circle, and so we were all tortured, including some students under the age of 18. It was a terrifying and traumatising experience.

Following our ejection from the building, some students were arrested and charges were laid. Some others were approached by undercover police officers dressed as students, who were soliciting information. They gave themselves away partly by the questions they were asking us and partly by their clothing that contrasted with that of the protesters.

The mainstream media did not expose the police torture of students that occurred at UTS, and elsewhere at Sydney University. The media instead focused on us as troublemakers and drew attention to the food waste that had accumulated in the offices. However, the UTS Students Association published and widely disseminated a broadsheet newspaper of the police violence, including with pictures of the vicious German Shepherd bites.

Following the protest, UTS Council refrained from introducing up-front fees for a number of years. Unfortunately, Sydney University went on to introduce full fees soon after.

Dr. Rowan Cahill on ‘The Siege of Sydney University’ in 1968.

“The Seige of Sydney University, 1968.”

[The author was a participant in these events. He is co-author with Terry Irving of Radical Sydney (UNSW Press, 2010)]

New South Wales Police Special Branch (1948-1997) was established to curtail and thwart labour movement militants and leftist activists generally. During the 1960s it targeted the student and anti-Vietnam War movements. Head of the outfit in this period was Detective Sergeant Fred Longbottom. He was an in-your-face operative, for instance sidling up to protest newcomers and referring to them by name, just to let them know he knew who they were and implying threat. At large demonstrations, Longbottom and his cronies often directed regular police as to who to arrest.

On 2 August 1968 Longbottom and a colleague visited Sydney University to test a new long-range recording device on a scheduled Front Lawn student protest meeting. Arriving in an unmarked pursuit Mini Cooper S, their entry on campus was tagged by observers and reported to the university’s administration. Vice-Chancellor Bruce Williams, no friend of student militants but wary of the inflammatory potential of this incursion, despatched his security chief to advise the officers to decamp.

By the time he did, it was too late. As the Mini was about to leave its covert station near the Tennis Courts opposite the Front Lawn, a prominent student militant spotted the vehicle, identified its occupants, and placed himself in front of the car. Threatened with arrest he retorted, “Go ahead”, and proceeded to deflate the front tyres.

Drama is hard to hide; he was joined by comrades, and eventually a large crowd. When the officers tried to leave campus on foot, they were detained. Their recording equipment was seized and the car trashed – engine wiring ripped out, fuel tank filled with sugar cubes from the main campus eatery, its body festooned with anti-war stickers shaped to form swastikas.

Police reinforcements and the media arrived simultaneously in droves. A tense, long, potentially violent stand-off followed as angry students erected barricades from garden furniture and blocked police entry to what in those days was a more confined campus than today. It was before the advent of tasers, pepper spray, the Riot Squad, attack dogs, and special punitive legislation.

Leading activists got together to figure out what to do with the captives and how to avoid prosecution. They came up with the idea that in exchange for their release, the police needed to publicly sign a document promising never to spy on campus again. A meaningless document of course, but symbolic and humiliating. A senior officer was sought to do the signing, and Acting Metropolitan Superintendent Fred Hanson reluctantly arrived and did the honours.

Document signed, the captives were released unharmed. Their crippled car was carried by students and dumped in the evening traffic of Parramatta Road. The media dubbed the event ‘The Siege of Sydney University.’ No prosecutions ensued. Later, however, Special Branch took revenge against the tyre deflater with a frame-up, but that is another story.

Shovan Bhattrai on the education protests this year.

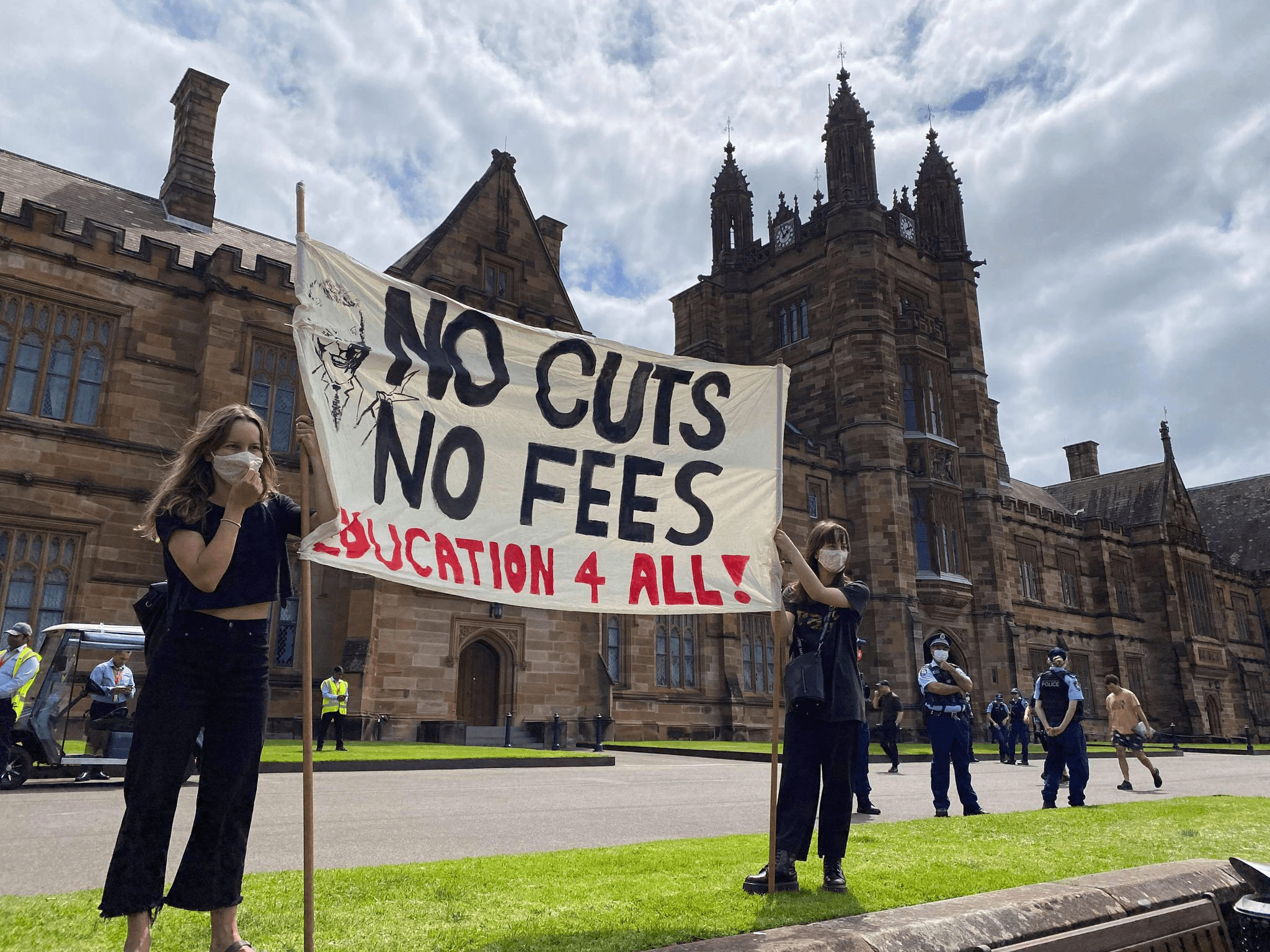

I was violently thrown into the gutter by NSW Police at the student demonstration against education cuts on October 14th. In the video of me being thrown that has since gone viral, I am picked up like a ball and hurled through the air as a swarm of riot cops try to shove me back from marching onto Parramatta Road. I was left with bruises up the side of my body and a deep graze on my elbow requiring four visits to the doctor to address the wound.

My experience at this student rally was not an exception. NSW Police mobilised in full force to intimidate student protesters at Sydney University on October 14th, sending multiple squads of riot cops and mounted police onto campus. Their policing was aggressive and intimidatory, chasing us around the campus, kettling us in, riding police horses into crowds, smashing phones, and violently shoving us back from the road. They bent wrists back, including that of UNSW Education Collective activist Macy Reen, and kicked out legs from under student protesters when arresting them and giving them $1000 fines. They dished out the same treatment to Sydney University Law Professor Simon Rice who was only attending as an observer.

Unfortunately for NSW Police, their attempts to intimidate student protesters and drive us off the streets have backfired. A wave of public outrage and publicity followed in response to Simon Rice being arrested and myself being violently shoved. The incidents shone a light on the cynical application of the NSW public health measures by the police, state government, and the courts, to stamp down on our right to protest. While football stadiums, casinos, and a litany of profitable enterprises were reopened across NSW, the authorities facilitated an effective ban on protests.

Since that date, the Liberal government has been forced to retreat. The state government is now allowing demonstrations of 500 people to go ahead, up from a previous public gathering limit of 20. This concession is a huge victory for activists. It proves that the public health grounds for clamping down on protests are a sham, that they have always been about political repression. And it proves that activists were right to defy the ban on protests. It was right to defy the government and the courts and to stand up to escalating police attacks.

The fight must now continue. We should not accept the ongoing restriction on our right to protest with a cap of 500 attendees, and we must continue the fight to overturn the hefty fines levelled against protestors. We should challenge the existing restrictions on our right to protest pre-COVID.

This concession on the right to protest is also a victory for every social justice campaign, including the continuing campaign against education attacks. The next step for NSW education activists will be 1pm this Wednesday at Sydney University at an NTEU rally against job cuts and police repression. UNSW staff and students have organised a speak-out on their campus against police repression of student protests for the same time.

The concessions we have won on the right to protest should be celebrated as a massive victory for activists in the education campaign. We need to take the same approach of organising mass, defiant resistance on the streets in our fight against every injustice in our society.