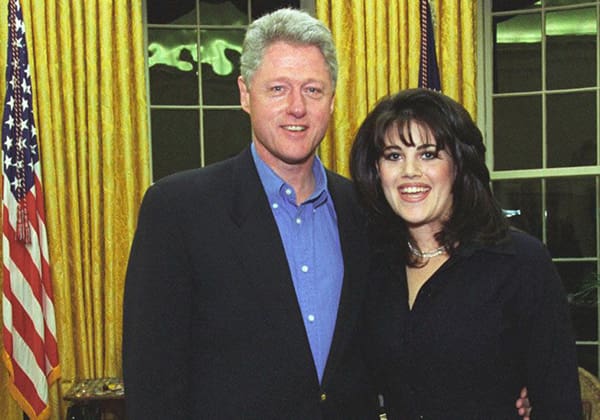

1995 was full of notorious celebrity romances. Bill Clinton “did not have sexual relations with that woman” Monica Lewinsky in the White House. Socialite Patrizia Reggiani ordered a hitman to murder her ex-husband Maurizio Gucci (yes, that Gucci) after he left her for a younger woman. And Baywatch starlet Pamela Anderson married Motley Crue drummer Tommy Lee within 96 hours of meeting, leading to a tabloid-friendly union characterised by drugs and violence.

All three of these scandals have adaptations due for release within the next six months. American Crime Story: Impeachment will no doubt spur a million breakdowns of what’s factually correct and what’s just a dig at Clinton for the sake of it. As the pre-exam blues set in, we’ll turn to House of Gucci to muse on a powerful family’s savage sense of fashion and morality. Sometime next year, we’ll binge the fallout of one of the first celebrity sex tape scandals in Pam & Tommy. Each of these stories is grounded in the women, who history has proven to ruin in scandal more readily than men. Concurrently, relatively “modern” media phenomena like 24-hour news networks and internet gossip columnists painted these incidents in highly dramatic strokes, revamping celebrity sex scandals from risqué rumours into prime time entertainment.

Today, audiences are deeply embroiled in an invigorating sense of nostalgia, using sitcom revivals, platform sandals and the Bennifer reunion to be transported back to a glorious COVID-free era. Indeed, research conducted by the University of Southampton has found that nostalgia counteracts loneliness, anxiety and boredom, and can quite literally “increase meaning in life”.

But there’s something bigger going on here. As an audience that’s post-postmodern and hyper-analytical, we demand more complexity in our stories. We want to re-explore, re-evaluate, and re-experience the past through a new lens to better understand it. In a post-#MeToo era, these productions are notably a chance to dive into the women’s perspectives, who (regardless of their level of guilt) found themselves decimated and often de-legitimised by a subsequent media storm. And these tempests can last for years. In 2013, after nearly two decades, one particularly bombastic magazine headline exclaimed “Sex Tape Found! How Monica Seduced Bill…”

On that note, the jury’s not out on the ethics of these adaptations. Their critics argue they’ll just bring up decades-old trauma for the sake of entertainment. In the case of Pam & Tommy, neither the titular pair nor anyone close to them is involved in the production; in fact, they all think it’s a bad idea. Anderson’s long-time friend Courtney Love went so far as to call leading actress Lily James “vile” in criticism of reinvigorating interest in a highly traumatic period that “destroyed” her friend.

Perhaps, though, this is the point. The focus of each of these productions is on a scandal: an event regarded by popular consensus as morally disreputable and therefore immensely intriguing. The subsequent media response spares no effort under these circumstances. Gucci’s murder was just the prologue to the infamy of a tragic “black widow”. Anderson and Lee’s already volatile relationship was overshadowed by the frenzy surrounding the first viral sex tape. And Clinton, Lewinsky and the rest of his presidency were swallowed whole by media scrutiny. The implicit focus of these upcoming adaptations is not just on what happened, but on the virality of it; the drama of the event rather than the event itself. If executed well, these productions will reach out, grab the audience by the collar, and say “What do you think of this now?”. In doing so, they promise to evaluate these events through a reflective, almost ironic lens. Our manic engagement with these events will be revealed as the scandalous act, rather than the events themselves.

In 1998, all of these dramas came to some sort of resolution. Clinton was impeached by the House of Representatives for perjury and obstruction of justice, but was later acquitted by the Senate. Reggiani was sentenced to 29 years in prison, but only served 16 of them. Anderson and Lee divorced, but would go on to give their relationship an unsuccessful second shot. Maybe in three years, we’ll rectify our vagrant fascination and declare we no longer care for decades-old sex scandals, but I doubt it. To quote Bo Burnham: “apathy’s a tragedy and boredom is a crime”.