Why do I love everything that has to do with kitchens so much? It’s strange. Perhaps because to me a kitchen represents some distant longing engraved on my soul.

– Banana Yoshimoto, Kitchen (1988)

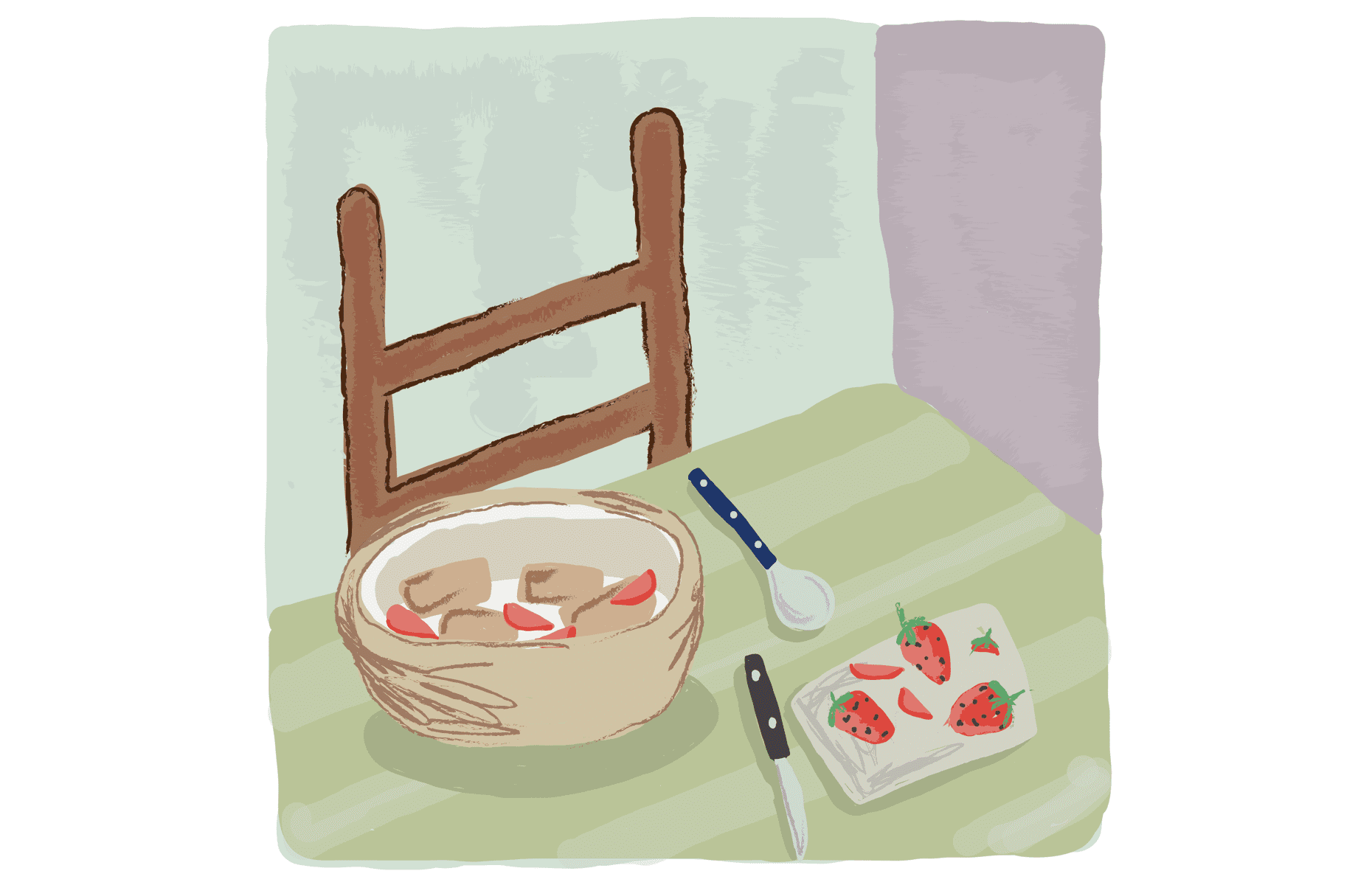

In my kitchen, there is a spot where I like to sit. My spot is a nook between two cupboards, an ashen benchtop that cradles me as I eat weet-bix and strawberries each morning, my legs swinging below. There are chairs in my kitchen, but I prefer my spot. Above it, a little window hangs like a diptych. If you unclasp this window in the springtime, hints of jasmine will seep into the kitchen. I have sat in this spot ever since I was little, and I find it calm.

For Mikage, the thoughtful protagonist of Banana Yoshimoto’s Kitchen (1988), the kitchen is a similar place of solace. As she heals from trauma, she gravitates towards her spot. Here, cooking for others becomes a salve for pain: cucumber salad, okayu, pickled wasabi root, katsu-don, shared amidst the hum and gentle glow of her kitchen. Whenever another character faces inner turmoil — over grief, sexuality, loneliness — Mikage cooks. A simple meal brings a moment of peace.

The first time I read Kitchen, I sometimes glanced up from my reading chair towards my spot, the little diptych window, the lush green behind its panes, and I thought of the past.

In my family, we often giggle about my childhood eating habits. As a toddler, I adored pasta, to the point that I refused to eat anything else. I barely remember this, and therefore do not entirely believe it, but my extended family swears that it is true. My mother would clear the shelves of Lamonica’s, returning home to a grinning young boy in the kitchen. My aunt is from Calabria, yet she still claims that our pantry held the most impressive pasta selection she has ever seen. I would sit at the ashen benchtop, and from the bottom drawer, my mother would pull out a plate adorned by Peter Rabbit, draped in his blue coat and surrounded by delicate butterflies. This plate has a matching teacup, and the set is my favourite treasure in our kitchen. Before me, a little mound of tortellini, penne alla norma, spaghetti aglio e olio, would appear, and I’d eat my dinner as the sunset bathed our kitchen in crimson light. This story is completely exaggerated, a fairy tale of princely indulgence, but it makes everyone smile.

I remember the more recent times spent in my kitchen, as the final days of high school bled into the new year. Once, I decided that hot cross buns were too delicious to only make an appearance at Easter, and a friend agreed with me. We placed the dough on the windowsill to bask in the morning light, and after hauling the buns out of the oven, we shared a teal pastry brush to paint the golden crusts with marmalade. Whenever new friends and new loves entered the scene, my kitchen became a sanctuary. We would bake, drinking lovely hot tea as we gazed at a lorikeet perched on a bough outside, and a true connection would bloom. One day late last year, a few of my closest friends visited for lunch. They were all to leave for colleges, exciting journeys abroad, and a lunch was our way of saying goodbye. I raided the spice cupboard and the wine cellar, my friend made a two-tiered sponge that glittered in the afternoon shine, and we were adults as we sat at the spotted gum table and ate.

In the drawer below my spot, there is a navy-blue notebook. My grandmother has attempted to teach me a few of my favourite Persian dishes, and I have attempted to transcribe the recipes. This is a difficult task: she never goes by measurements, and I lack the bearings to understand what “a bit” really means. As we cook, she tells me of her childhood in Iran — how she and her six siblings would run home for lunch, grinning as paisley bowls of aush-e-reshteh appeared before them. She tells me of fleeing a war zone with rice cookers and seasoned pots. She tells me that my mother must cook with more butter and salt: it is our cuisine.

As I have grown up, I have begun to understand the importance of kitchens. For so many migrant families, kitchens are the only way back home. We cook to return to the community we lost, and to satisfy that distant longing for our roots. For all of us, however, kitchens are a space of love. We have our spots, our favourite meals, and our memories.

There is one passage from Kitchen that always makes me beam, and I can think of no better way to end a story:

When I’m dead worn out, in a reverie, I often think that when it comes time to die, I want to breathe my last in a kitchen. Whether it’s cold and I’m all alone, or somebody’s there and it’s warm, I’ll stare death fearlessly in the eye. If it’s a kitchen, I’ll think, ‘How good.’