Once the most pressing issue for medical researchers, the global eradication of poliovirus serotypes (or strain) 2 and 3 was an incredible leap forward for epidemiologists and public health experts. With only one serotype still in the wild, most of us will never know any sufferers of the virus’s most disabling type of infection, poliomyelitis.

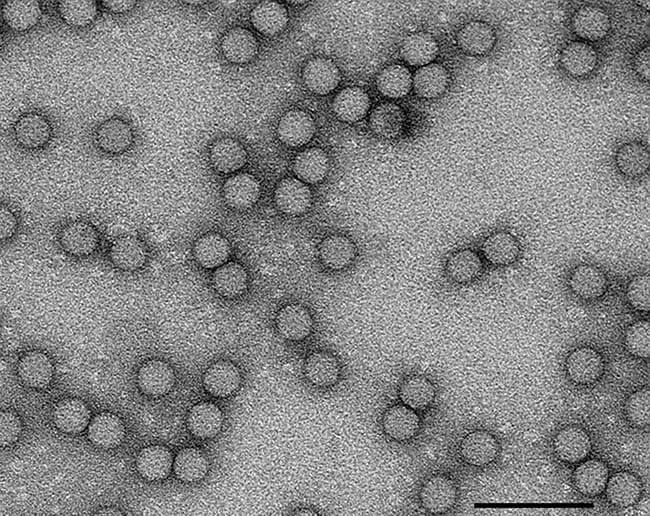

Poliovirus is spread via faecal matter to the mouth, meaning that it spreads particularly fast in areas with poor sanitation. The disease mostly affects children under the age of five as it gives lifetime immunity following infection. 75% of infections are asymptomatic but infected individuals can shed viral particles via their faeces for up to 30 days after their initial infection. Poliovirus multiplies in the stomach but can cause paralysis if it travels to the brain via the spine.

While less than 1% of infections lead to paralysis, the effects of poliovirus on the central nervous system can be far-reaching. For example, post-polio syndrome can occur up to 40 years after infection due to the lasting nerve damage caused to the grey matter. To make matters worse, if you have a faster recovery from the original infection, you are more likely to end up with post-polio syndrome.

Polio has existed for millennia, affecting millions across the planet from 1400BC. Widespread panic only arose once the epidemic reached wealthy and otherwise healthy white children in the United States. The most notable sufferer was President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who was quickly paralysed. He launched fundraisers and campaigns to promote research into treatment and prevention of the disease.

Research was initially slow going as the belief that polio multiplied in nervous tissue made it hard to grow in the lab. The first effective vaccine was created in 1953 by Jonas Salk and his team at the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania, USA.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 16 million people have been saved from paralysis due to the global immunisation campaign. The inclusion of vitamin A in the oral vaccine has also reduced child mortality in communities susceptible to malnourishment.

Despite the monumental achievements of the public health movement at the time, vaccine-derived poliovirus is an enduring challenge for eradication efforts. Initially, the Oral Polio Vaccine (OPV) was favoured as it is more accessible to disadvantaged communities. Consisting of a weakened virus, it is easy to administer as it is non-invasive and unpatented.

An alternate injectable vaccine consisting of a completely killed virus, one that most Australian children would have received, was much less dangerous but more complex to administer.

However, 3 in 100 million doses would develop paralytic polio. Vaccinated individuals can shed viral particles into their environment following their dose, meaning that while those who are unable to attend clinics can gain some immunity, immunocompromised children face the risk of developing vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV). VDPV has mutated over time to become more similar to the wild virus, spreading easily through faecal-oral or respiratory means.

Public health organisations are waiting until the third wild poliovirus is eliminated before they stop administering the oral vaccine, considering PDVP’s extreme rarity. There were only 33 wild poliovirus cases in 2018 according to the WHO, and there hasn’t been a case of the third strain since 2012 as global health organisations wait for its eradication to become formal.

While two of three serotypes have been eradicated, a fourth has emerged. The disadvantages of the oral vaccine now outweigh the benefits but it has been difficult for public health organisations to adapt to VDPV’s emergence. While the OPV has been instrumental in making sure that everyone from all backgrounds can receive some form of protection from the virus, the way forward must shift focus from plain accessibility and pivot toward effectivity.

Polio eradication is a major feat and has saved millions of lives. It has also been instrumental in developing public health infrastructure that still serves disadvantaged communities. The oral vaccine’s non-invasive nature is a key reason for this, but we must keep in perspective that its development was contingent on the suffering of white Western children. Furthermore, the story of polio demonstrates how important accessibility is when developing medicines made to be administered globally.