For young people finding their way out of the closet in Sydney, Oxford Street is ostensibly the symbol of an out, proud, and inclusive queer life. But everywhere you look, it’s white, cisgender gay men who are the public face of queer culture and dominate the nightlife scene. So, where do all the lesbians and bisexual women go?

It’s disappointing that despite the apparent mainstreaming of queerness since the marriage equality campaign in 2017, the only lesbian bar the younger generation frequents is Birdcage at the Bank Hotel on Wednesdays – a weeknight, no less! Birdcage’s relocation in early 2020 from Slyfox to a much smaller venue at the Bank transformed the event. Regrettably, I never went to Slyfox when it was open, but as a friend tells me: “There was an older crowd then and a more diverse mix – the sorts of people who would get looked at on the street – bulldykes and people with facial piercings and colourful hair. It was a lot cheaper and there were pool tables, more nooks and crannies to hang out in.”

Arriving at my first Birdcage night after the 2021 COVID restrictions were lifted, I joined a queue for two hours downstairs, waiting for others to leave so that more of us could enter. There is evidently a demand for more lesbian spaces. Finally making it upstairs, we had to twist through a packed crowd to get to the stage, with familiar faces everywhere you looked. While being surrounded by other people’s bodies and loud music would make me claustrophobic at most clubs, at Birdcage it felt like stepping into another world.

What sets Birdcage apart from other queer nightclubs is that lesbians and bisexual women make up the majority of its attendees, rather than the minority. In conversation with friends about the value of lesbian-centric spaces like Birdcage, the perceived level of safety against sexual harassment and objectification from men was a significant factor affecting enjoyment.

“I feel less like I’m going to be groped,” said one friend.

“When there’s men around we can’t indulge in sexuality the way we do at [Bird]cage. The reason everyone feels so comfortable making out is there’s no men to sexualise it on their terms,” said another.

The consensus among my friends was that most queer nightclubs, which centre around cisgender gay men, don’t provide a break from patriarchal structures:

“I feel like I can unashamedly be myself in a way I can’t be around men. Even if they’re gay they still carry the socialised power they were raised with.”

“Honestly, I think what I like about it is that it’s all women.”

Lesbian-centric nightclubs foster an explicitly queer hookup and dating culture that is shunned elsewhere, and provide a space for comfortable self-expression. Ever-present in our day-to-day lives as queer people is the underlying fear of being judged, harassed, or hate-crimed for holding hands or kissing in public. It’s insidious. But stepping into a space where you’re the majority can allow you to shake off that burden – to be yourself and not have to be on alert for homophobic harassment.

In the face of a historical silence around lesbianism, spaces for queer women have often been fleeting and ephemeral. Birdcage’s relocation is just the latest in a pattern of constantly changing and disappearing spaces. In Unnamed Desires: A Sydney Lesbian History (2015), Rebecca Jennings outlines how, in contrast to the legal discourses around male homosexuality, the unspoken topic of desire between women became a taboo in Sydney’s society. She argues that this mechanism of silence “prevent[ed] the formation of lesbian subcultures and identities.” Often financially dependent on men in their lives, many women had no choice but to stay in their marriages, never having the opportunity to openly explore their sexuality. Those who did risked being ostracised by their family, friends, and losing their jobs.

Consequently, far more has been documented about the gay male scene in Sydney than the lesbian scene, with evidence suggesting that lesbian and bisexual women didn’t have a large presence in the commercial bar scene until the 1960s. Jennings suggests that the laws against women drinking at public bars and the pressure to conceal one’s identity meant that lesbian spaces primarily took the form of private friendship groups. These were centred around house parties and sports clubs rather than socialising in public, which came much later.

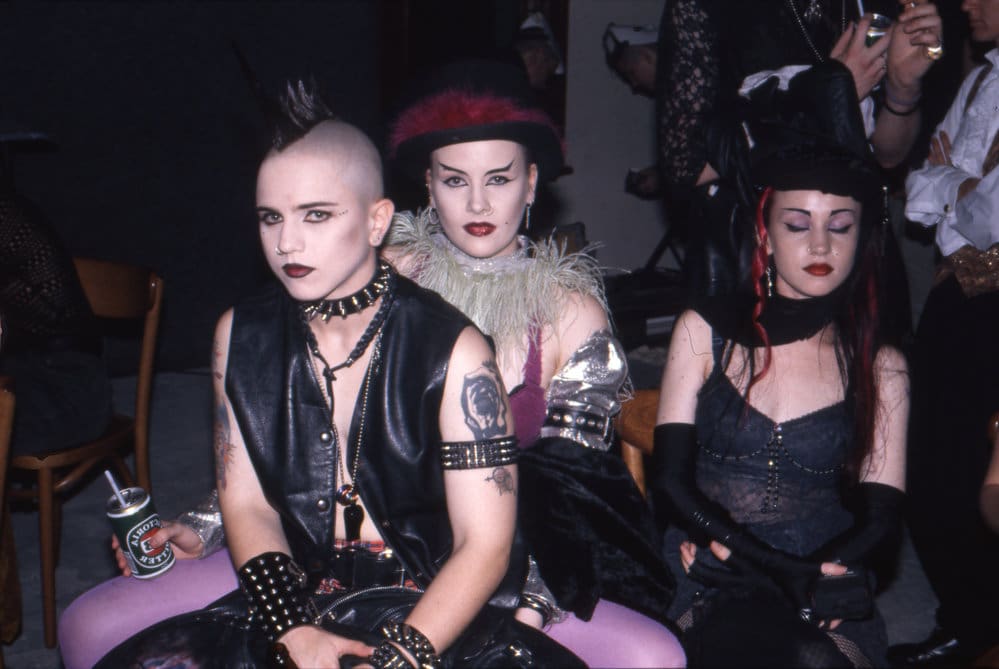

For a first-hand testimony of the queer scene of Sydney’s past, I spoke to lesbian photographer C. Moore Hardy, whose work was featured on the first cover of gay and lesbian magazine the Sydney Star Observer. Hardy is a social documentary photographer and has an extensive collection of photographs documenting the community at Mardi Gras, queer social events, and rallies. These photographs are a treasure trove of subcultural memory, showing us the potential of earlier spaces and how we might carve out new ones today.

In our conversation, Hardy noted that lesbians have always been part of the queer liberation movement, but that they make up far less of the documented history “because we don’t record history the way the boys do enough, [and] because women have been more in the closet than men have, we disappear.”

“It’s just appalling … And that’s one of the reasons I’ve started documenting the community. I couldn’t see images of women, full stop, that I could relate to. So I wanted to document as much as possible of what I was seeing. And that was a lot of women who were, you know, edgy, interesting, the leather girls.”

“Because of my Mardi Gras stuff, I’ve always documented the subcultures within our subculture. That, to me, is really important because they’re the really invisible crowd. I mean, we see so many white gay boys … If queer culture is to be represented fully, it has to be inclusive.”

Without the efforts of writers, artists, and photographers such as Hardy keeping record of Sydney’s vibrant alternative queer cultures, we would not have such an extensive archive to look back on and say: we have always been here.

And what is recorded only just scratches the surface of a history that has fallen through the cracks.

Many of the people who were part of that scene are no longer here because of the AIDS crisis that fundamentally reshaped Oxford St: “It was like a whole lot of men going to war, they just died. And it was a culling of the most creative people,” said Hardy.

“Each week in the paper, there’d be, this person died and their name, and it would be five or six people per week, would die. And you’d see their obituaries in the paper, which was just phenomenal at that time.”

Up against a hostile government and religious groups, the queer scene in Sydney has always had a marginalised existence. Lesbian spaces have been among the most ephemeral, which Hardy attributes to the fact that “the girls have never really had the same amount of money. There’s never really been a dyke place, you know, a bar, per se.”

“There were roving places … they’d have it in a warehouse or public places that were available for rent.”

“Dawn O’Donnell ran one nightclub that came in and lasted for a number of years because she owned the place. Those were early days on Oxford St. It then got sold to somebody else at some point, that’s the nature of the lesbian scene.”

Ruby Reds was the nightclub owned by O’Donnell, a ‘girls only’ venue in Crown St, Darlinghurst and the most popular lesbian bar in the 1970s. Notably, the space is now a gay male cruise club.

In those decades of intense political debate, separatist feminists wanted exclusive spaces for women, to break apart from patriarchal institutions and develop alternative community values. Hardy told me: “They [gay men] would not go to certain things … The exclusivity did occur in those days because there were a lot of women who didn’t want to associate with men.”

However, some separatists in Sydney wanted to bar transgender women from membership to feminist and lesbian clubs, causing conflict in the 1990s. In today’s climate of rising transmisogynistic violence and rhetoric from the conservative media, politicians and feminist circles alike, calls for more lesbian spaces must be explicitly trans-inclusive.

On the topic of queer activism after the marriage equality win, Hardy said: “What really needs to happen is people need to stay vigilant. As queers we can’t not be vigilant.”

She lamented how the spirit of Mardi Gras has been lost in its move to the Sydney Cricket Ground, a ticketed event that is more spectacle than protest: “Keep going on the streets … I think it’s really important that each generation shows their spirit by doing what they need to do, and being on the streets is what we really need to do. We need to cause disruption.”

It is Hardy’s photos of Pash On, a political demonstration where members of the queer community kissed on Gilligans Island, Taylor Square, that stand out to me when thinking about space. In lieu of fixed institutional and commercial spaces, a lesbian space can mean a spontaneous protest in the street. It can mean bringing all your friends to one cafe like the girls in The L Word, attending a local performance or exhibition, an Inner West house party, a Facebook group chat…

Perhaps the fleeting, often undocumented nature of queer spaces necessitates a rethinking of what spaces we consider legitimate marks of community in the first place. Isn’t a queer space anywhere we exist? Still, a bar where you don’t have to wait two hours to enter would be a nice start.

Nearing the end of our interview, Hardy puts it succinctly: “We create our own spaces. It’s what has to happen.”

“You have to make your own lives, you have to push those boundaries that exist, always push the boundaries…”

As with any of the rights we’ve won as queer people, change doesn’t come from those in charge. A better future will only come when we go out there and make it happen ourselves.