Following in the footsteps of exhibitions past, the Tin Sheds’ current showing entitled Art & Activism in the Nuclear Age is a striking display of politically charged, captivating works of art. Ranging from screen-prints to manga and paintings to installation, the exhibition encompasses artistic responses and criticisms of the Nuclear Age, investigating ways to overcome and progress “in the search for peace and total nuclear disarmament.”

The exhibition is curated by Dr Yasuko Claremont, author of critical texts such as Legacies of the Asia-Pacific War and honorary senior lecturer of Japanese language and literature at the University. Taking place more than 75 years after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by the United States, Claremont’s exhibition brings together generations of artists from Japan to Australia — including artists who witnessed the nuclear attacks, and others who lived to faced the consequences.

Three salient themes ran throughout the exhibition space: representation, recognition and resistance. In a world where there are estimated to be over 13,000 nuclear weapons, it would be easy to criticise the efficacy of ‘representing’ nuclear disaster through art as a means to dismantle it. However, what this exhibition makes clear is that artistic representation of horrific violence and disaster achieves what mere words and documentary photography often can’t: the emotional dimensions of humanity in crisis.

Contextualising what’s to come, the exhibition opens with a metres-long timeline of the nuclear age, consisting of 40 disasters and developments occurring over the last 80 years. It begins in 1941 with the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbour and ends on 20 January of this year when the Doomsday clock stood at 100 seconds to midnight (for the third year in a row). The expansive timeline serves as both a monolith and a warning as it overlooks the gallery space — a constant reminder of the histories from which the artworks grew.

Courtesy of the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum, Fukami Noritaka’s 1946 work Storm over Kiyō — Tale of Nagasaki is displayed as a panning video of the 11 metre watercolour shoji scroll. Not displayed to the public until the 1980s due to censorship imposed by US, British and Australian Occupation Forces, Noritaka’s picture scroll depicts the horrors of Nagasaki. Possessing a raw, entrancing quality that draws viewers into the tragedy of the scene, the work is a direct product of Noritaka’s own experiences rescuing people from the city just three hours after the explosion.

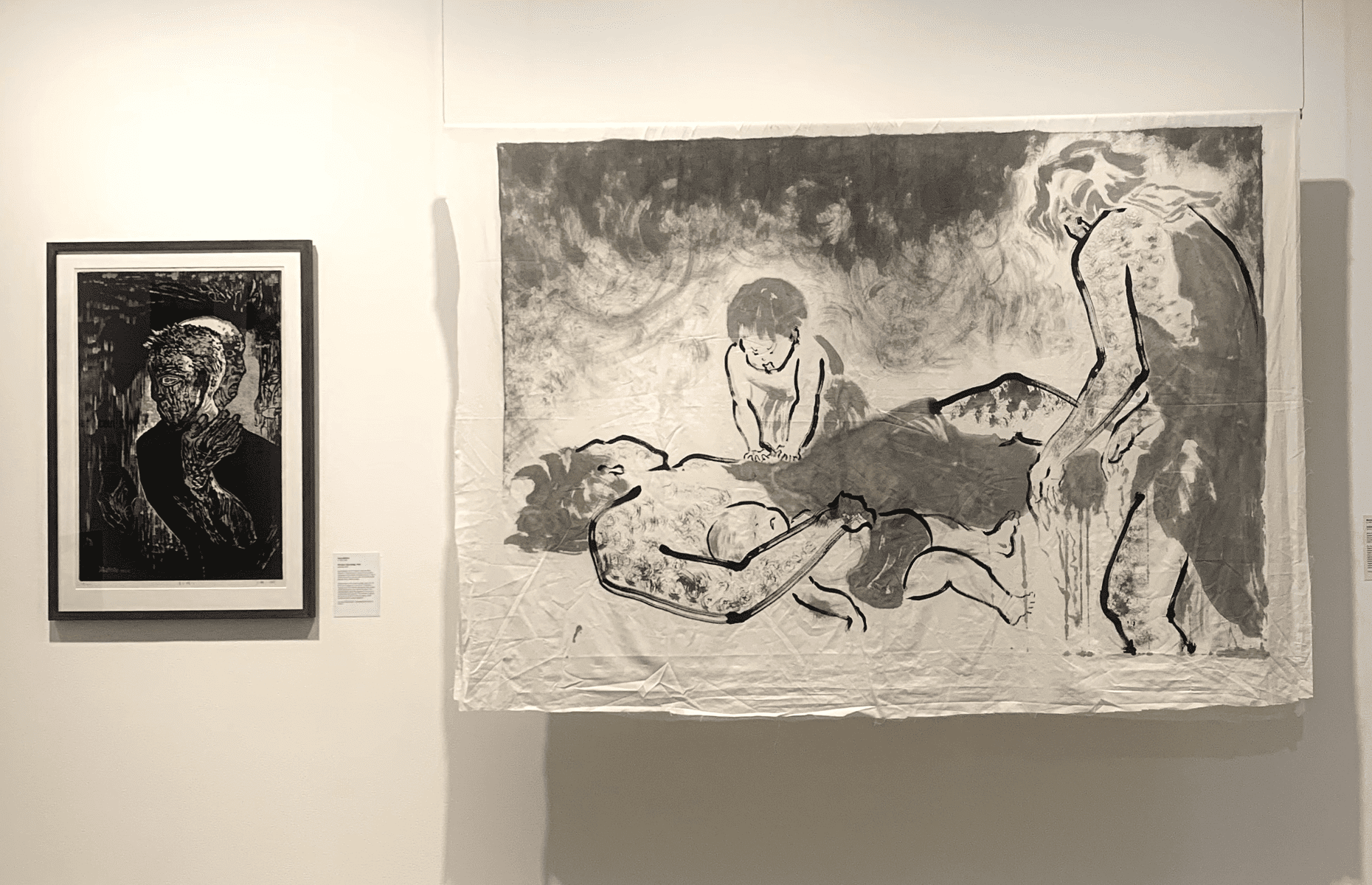

The subsequent work from 1963 entitled Ikinokori (Surviving) by Ueno Makoto is a monochrome woodcut from post-war Japan. The woodcut print-media movement centred itself around working-class people and the resilience of the body. Representative of the persisting spirit of the time, the work heralds the strength of love between the two subjects,depicting two people embracing during the firey-flash of Nagasaki. The tragic aftermath is evident in the charred black of the ink.

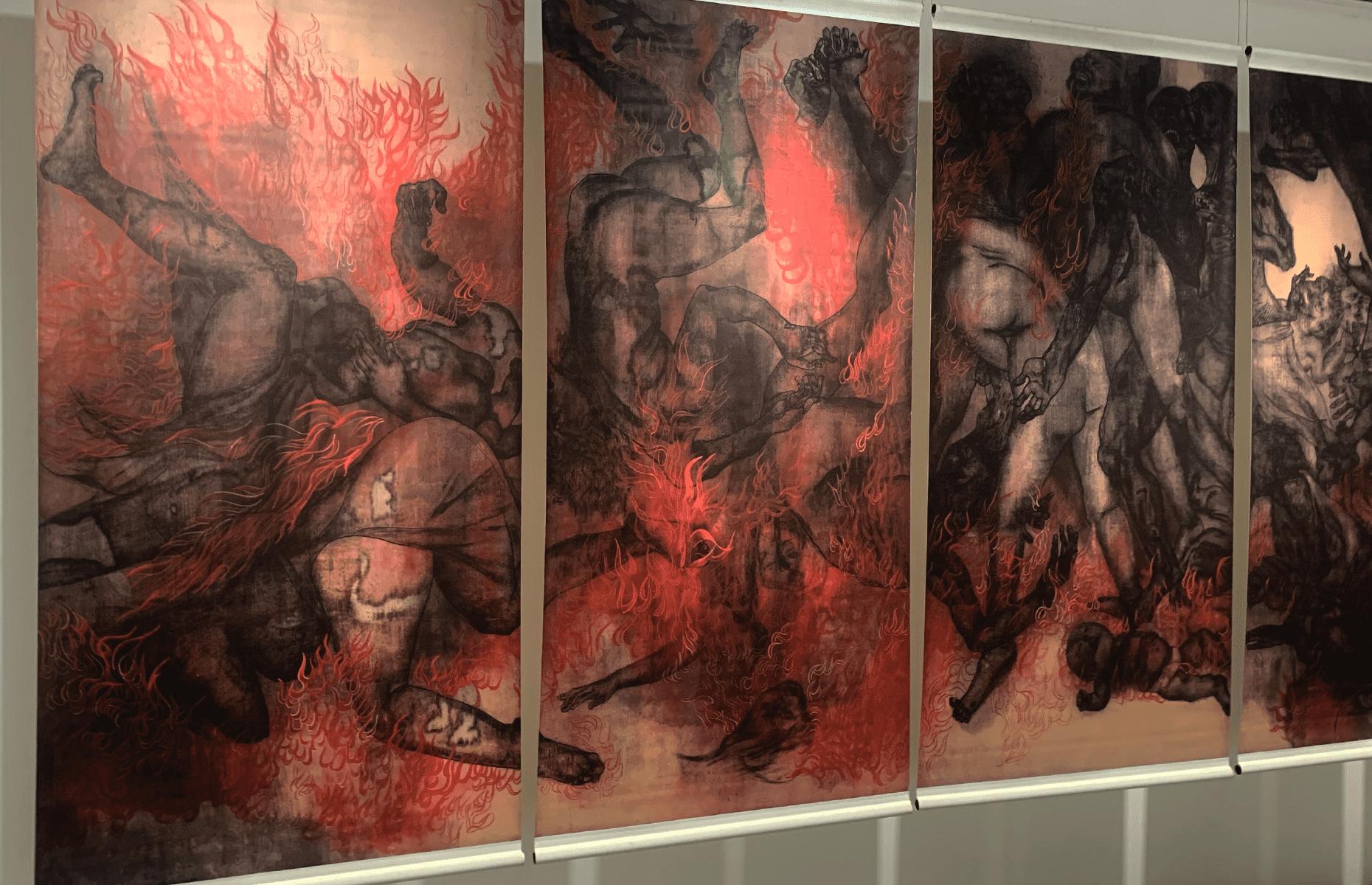

The exhibition’s centrepiece Fire (1950) by Iri and Toshi Maruki is a graphic yet stunning amalgamation of red flames and burnt bodies. “There is no greater hell than people killing people,” Iri said, regarding the work. The eight panels on display are reproductions, yet the contortions of charcoal and limbs remain powerful tools that depict the terrors the pair witnessed in the aftermath of Hiroshima.

Standing in contrast to these works is the bright rainbow of hanging paper cranes that comprise the exhibition’s standalone installation work. The vibrant folded cranes were made by visitors and school children who attended the Black Mist Burnt Country: Testing the Bomb — Maralinga and Australian Art exhibition which toured Australia across 2016-2019. Created in honour of Sadako Saski, a child who developed and ultimately died from leukaemia after Hiroshima, the cranes represent the child’s own effort to fold 1000 cranes — which according to Japanese legend would allow her wish to be granted. At the end of the exhibition, the cranes will be sent to the Children’s Peace Monument in Hiroshima.

The theme of nuclear imperialism was highlighted by the exhibition in the Australian context, most notably the British testing of nuclear bombs between 1952 and 1963 in Maralinga and ‘remote’ First Nations land. The gallery-wall of works entitled Life Lifted into the Sky (2016), created by a collective of three generations of Yalata women, is a powerful display and indictment of this nuclear testing. The works depict the damage inflicted on local Indigenous communities surrounding the testing sites, and highlight the role of the British in conducting forced removals in 1951 prior to the testing.

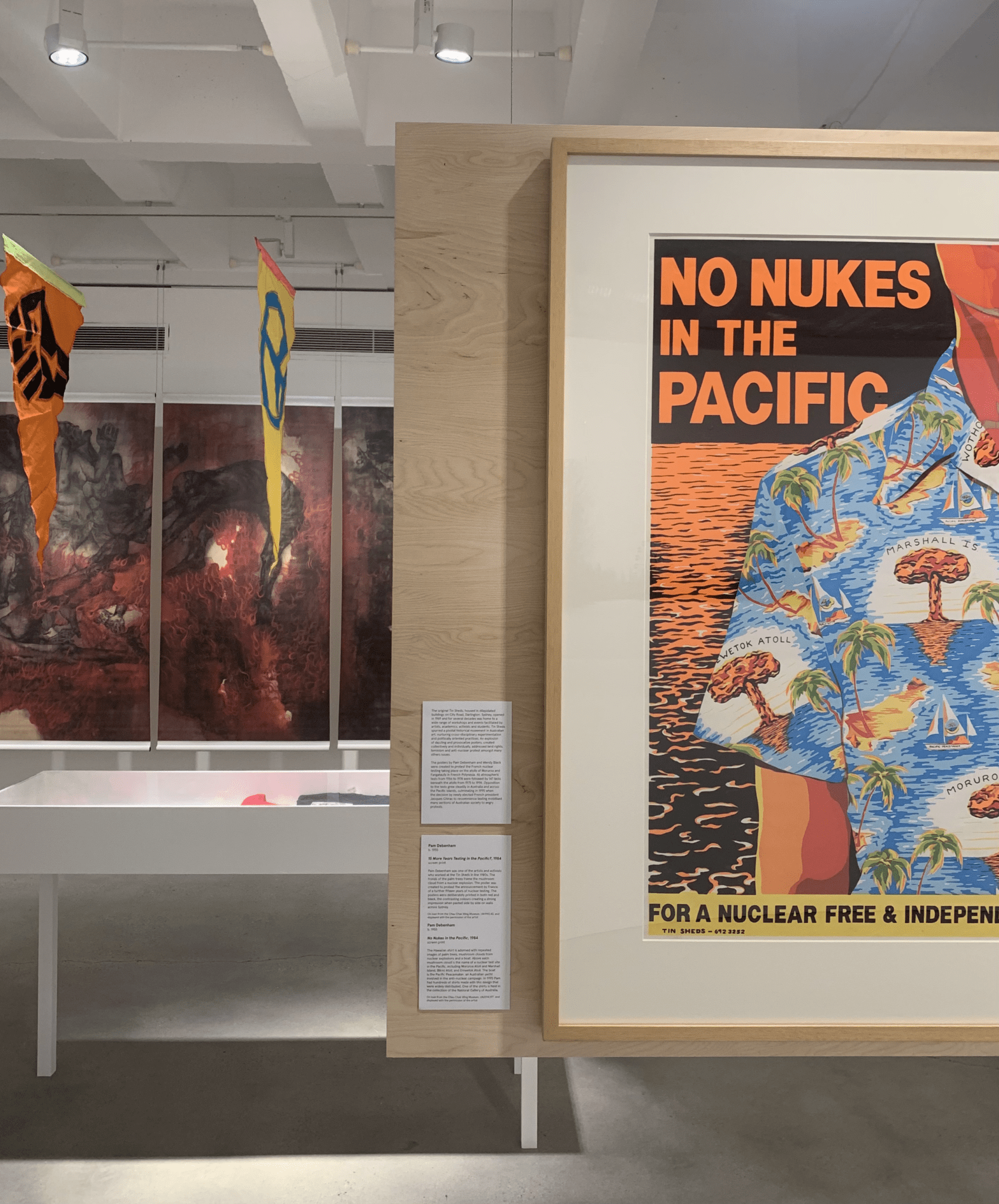

Showcasing protest of nuclear testing in the South-Pacific, the exhibition displays the screenprint works 15 More Years Testing in the Pacific? (1984) and No Nukes in the Pacific (1984) by Pam Debenham — both created at the Tin Sheds workshops among USyd’s activist art collectives of the 1980s.

Though not made explicit through a given artwork, when experiencing the exhibition it was impossible to overlook the current nuclear threat within Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It was only on the 24 February this year when Russian military forces entered the Chernobyl Nuclear Exclusion Zone in Ukraine, causing a spike in radiation levels and increasing the risk of a nuclear accident in the area.

Setting out with the intention to “highlight the consequences for humanity of a nuclearised world,” the exhibition unquestionably achieves its goals.

The exhibition is open until May 14 at the Tin Sheds Gallery — 148 City Road, Darlington.