“Be a legal consultant, not a lawyer,” my aunt would always say. She worked in HR and told me it was naive for an Asian boy like me to aspire to become a lawyer – a job in her eyes reserved for the white elites.

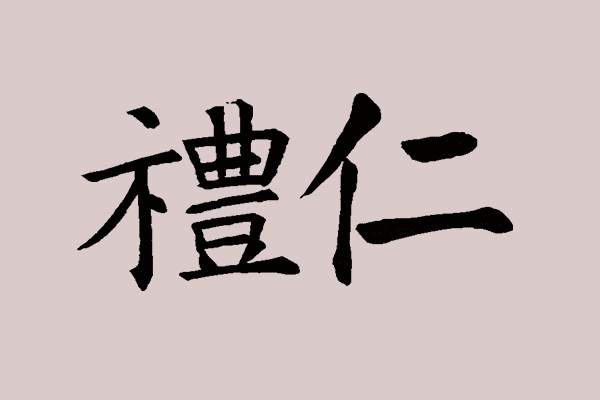

Growing up as a Chinese-Australian, I always felt as if my community was implicitly upholding the systematic inequality we found ourselves in by practising the Confucian value of ‘Li’ deeply rooted within our culture.

In Confucianism, ‘Li’ is described as the “heart of courtesy… of observance of the rites” by Doh Chull Shin, a Jack W. Peltason Scholar-in-residence at the University of California. At the root of Confucianism is a belief that everyone was born with a predisposition to benevolence. However, through environmental influence and practices, people drift apart from their innate potential. To correct this and build a harmonious society, Confucius suggests people need to practice Li, or act in accordance to the social standing they find themselves in. As a result, Li by nature is at odds with resisting the social order. While I initially believed this value set would hamper any attempts to counter prejudice and inequality, a closer reading of Confucianism in fact reveals apt philosophical foundations for resistance.

The Analects: “By nature men are similar; by practice men are wide apart”

The practice of Li is easily observable in my culture and throughout my life. Since childhood, elders taught us to be submissive in front of authority whenever we observe one; to not speak, to follow every request, and to never challenge.

Although Australia is proud of its multicultural environment, inequalities based on ethnicity are still obvservable in everyday life. For example, at school, many of my white friends wore shoes that fit them and had pocket money for the tuck shop, whereas children who looked like me wore oversized secondhand uniforms and brought packed lunches. What I used to envy the most, however, was how many of my white friends dared to pursue their dreams, whilst I along with the other kids understood our chances of graduating high school to be closely tied to our parents’ income.

It also meant I understood my chances of becoming a lawyer were slim because of my background…

My frustration compounded when I felt those around me were treating these inequalities like another authority through Li. We acted as if we were forbidden to speak out against these barriers in our lives. Whenever we hear about others leaving Australia, because they could earn more elsewhere, we could only sigh. Perhaps for those of us who stayed, we had hoped that by not raising our voice meant we could be accepted by the Australian hierarchy one day.

Eventually, my family became one of those who decided to leave. In 2017, after 4 years of pursuing the Australian Dream, we left the country to return to my parents’ home. Of the many reasons, one of which was due to the lack of opportunities available for my parents in Australia. We left without a word against the status quo, or as we would say in Chinese – Bu Ken Yi Sheng (not making a single sound).

Unbeknownst to many of us, the dominance of Li in my culture, according to Shin, has perhaps been the indirect result of my people’s history.

During the Han dynasty, a system of one-way obedience known as the “three bonds”, thought to have summarised Confucian values, was prescribed to the Imperial Court to formally establish the power of the Emperor. This system was preferred over other facets of Confucianism to uphold authority.

One of the many values hidden as a result, is ‘Ren’ – compassion, a love for others.

For Confucius, to be compassionate and Ren is to form every relationship through shared humanity. Confucius dictates that the coexistence of Ren and Li is necessary in a harmonious society. Li stresses respect for authority and hierarchy for efficiency, whereas Ren stresses the importance of compassion with one another for harmony. It is only through the two that people’s innate benevolence can be found again.

The Analects: “Loving all men… treat others as you would wish to be treated yourself.”

In the context of the resistance for racial equality, to practice Ren is perhaps to adopt the worldview of latter-day Malcolm X. After visiting the Hajj – a pilgrimage to Mecca – X saw a seismic change in his worldview. Standing with thousands of Muslims from across the world, walking in the same motion as everyone, and worshipping the same God, he realises that we are all the same. He came to the belief that it is wrong to fight through the alienation of the other side, all while never giving up on changing the status quo. He realised the importance of building dialogue to demonstrate our shared humanity, showing compassion and ‘ren’.

Malcolm X in his biography wrote: “I’m a human being first and foremost, and as such I’m for whoever and whatever benefits humanity as a whole.”

During my time in Taiwan, I was able to see Ren practised by my friends, many of whom were perhaps favoured by the system. They helped me pursue my goal of becoming a lawyer that I had abandoned out of cynicism when I left Australia. Close friends constantly sent me information that would support me, like the E12 scheme or other transfer pathways. Some studied with me, while some of their parents would constantly reach out to mine to support us. Most importantly, they showed compassion and ren whilst letting us know they had faith in us, no matter the challenge ahead.

I am still on the pathway to achieving my goals, and I am now closer because of seeing Ren in the relationships throughout my life.

There are still intangible barriers that benefit some over others, but many are evidently willing and eager to dismantle them. If the other side is willing to do so, why is my community unwilling to try the same. It is time to abandon Li, and look at the world through Ren, appreciating our shared humanness with everyone and being willing to challenge systematic inequalities wherever we see.