Do you ever lay in bed at night and think: I wonder what it’s like to be a lesbian? Or maybe, I wonder if I am a lesbian?

If either of these are you, and you are interested in a deeply personal and unnecessarily detailed account on what it has been like for me, a lesbian, to live out my sexuality as a USyd student, please read on. If you are specifically the latter, and want a yes/no answer on who you want to fuck, I suggest also clicking here and here.

In last week’s Honi, I wrote a review of being gay. The review was intended to be humorous, but, in giving being gay a rating, I just couldn’t bring myself to pretend that it’s been a 10/10 experience. It has been incredibly frustrating, isolating, and difficult. Equally, it has also been joyous, fulfilling and rewarding beyond the bounds of what heterosexuality could ever allow.

Ultimately, being a lesbian has been an experience that I try not to think about too much, because if I do, the joy is met with a simultaneous grief, anger, or resentment towards the people around me for not understanding what the journey has actually been like (especially queer people). This feeling is, of course, relatively futile, and I am largely to blame, given I most often bring up my sexuality in conversation to joke about it, or talk about how hot women are. It’s also stupid, because people more generous than myself have made being gay great for me, showing me community in ways I hope everyone gets the chance to experience.

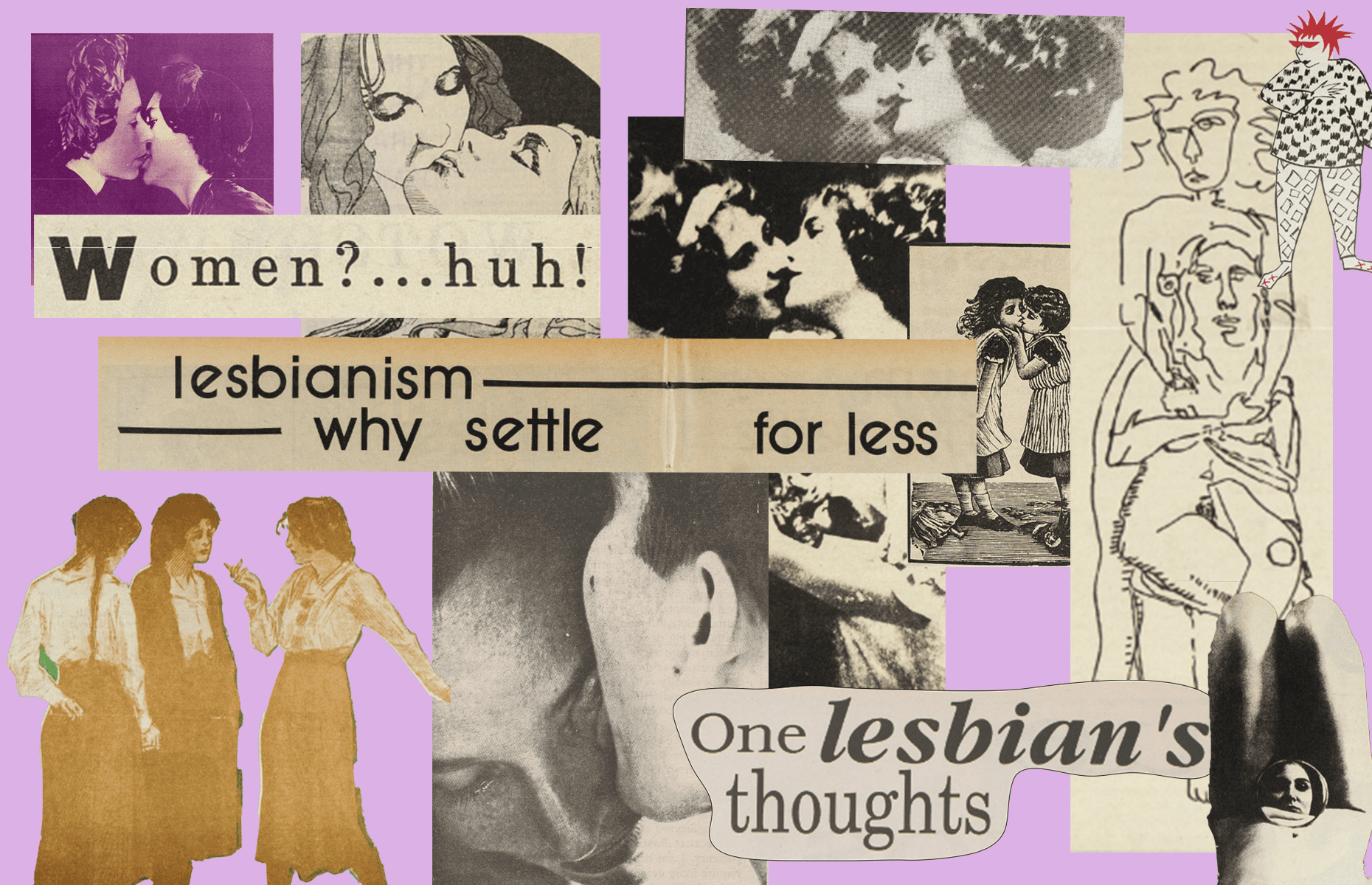

This article attempts to communicate both of those feelings at once, instead of neglecting their existence entirely, through the three-part account below of my journey through #lesbianism. My hopes are that 1) the people in my life may have an insight into what it’s like to want to sleep with women and 2) there is a lonely dyke on campus who feels like they have some emotional company.

Realising I was gay: this part didn’t rock

I knew I was gay in year 9 when I was watching Gossip Girl. Blake Lively was making out with someone and I thought it was so awesome. Then I noticed it was Blake Lively and not the bloke I found awesome, so I immediately slammed my laptop screen shut, cried, and banned myself from watching Gossip Girl for 12 months.

What confused me for so long about this disgust towards my own sexuality was that I’d never had any social indication that being gay was bad. I grew up around gay people — lots of them! My Mum told me Spongebob and Patrick were boyfriends in pre-school, and my best (girl)friend and I got married at her birthday party, complete with a kiss on the lips. In fact, my experience of gender and sexuality was so ideally socialised by my Inner City leftie parents that, in Year 5, I didn’t understand why I couldn’t play on the no-shirts team in a game of after-school soccer.

Due to this, I feel like I am a perfect experiment. You can remove a child from homophobia and hatred within your own home and community as much as you want, but it’s still there — on TV, on the radio, and eventually in the playground.

The peak of my shame came towards the end of high school. My friends all started kissing boys and having sex and I didn’t, and I could feel my youth slipping away from me. I tried partaking in the activities (spoiler: it didn’t work), drank too much vodka with the hope that if I vomited enough my subconscious would reset and I would no longer be gay (not even sure where this idea came from), and did extensive research into the potential that my homosexual tendencies may be epigenetic, eventually coming to the theory that perhaps if I conditioned myself to enjoy the presence of men, maybe a genetic trait would be (de)activated, and I would be at least bisexual. When none of this worked, I resolved that if I just waited until university, all of my dreams of a queer adolescence would come true.

University: false hope

SPOILER ALERT: University, for the first little while, crushed more of my queer dreams than it fulfilled. Perhaps it’s because my expectations of a magical dykeland were a little high, but arriving at USyd felt more isolating than anything up to that point.

I thought that uni would contain campus lesbians like those in American movies: crazy, hairy, stoner dykes who refused social interaction with men. Unfortunately, these are few and far between. I could probably count on two hands the number of lesbians I have met since starting university.

At uni, I found I didn’t quite fit in anywhere, and for the most part, being a lesbian has made me feel like an outsider. Upon reflection, this was largely due to the misc. space that the lesbian gender identity occupies. But of course, there have been highs and lows, both holding equal weight in shaping my experience.

The lesbians I did meet, I latched onto. Usually, they were older — realising that they would graduate before me, and I would be alone again, always left me with a deep sadness. It went without saying that they had the same experience as me; the queer people around them exuded confidence in their sexuality, but the space wasn’t quite there for them to do the same.

Dissatisfied with my experience, and determined to make it more markedly gay, I even tried to entirely manufacture queer culture on campus. I put every queer woman I knew in a groupchat. It was a semi success — we went to the Flodge a few times, but we now mostly use the group chat for updates on the Birdcage line. It certainly wasn’t quite the same as the lesbian societies present on campus in days gone by.

Every now and then, seeing a dyke on campus makes me overwhelmed with relief. But still, I rarely see myself reflected in my circles of friends. This is not an inherently bad thing — it’s important to mix with people who look nothing like yourself. But it’s isolating when those people look like each other.

Take note, teen dykes: you probably won’t find a huge friend group who had the exact same experience as you. But you’ll learn that there’s something lovely in how varied the experience of queerness is, and that there is equal, though different, joy to be found in how much you may learn from others.

#ItGetsBetter etc

I still grieve for the coming-of-age experiences that little 17-year-old me never got to have — not just because American movies say you’re meant to pash people at high school parties, but because those around me got to and I didn’t. But the experiences I had were made extraordinarily unique by these people too, and while I grieve for what I could have had, I’m so grateful to have gotten something entirely different. I know what I missed out on by being gay. But if I wasn’t, I’d have no idea I was missing all this. The experience itself wasn’t inherently positive, but good, community-minded people made it so.

They are why, for all my lamenting, I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Like for so many others, older queer women took on the role of nurturing my sexuality. I am almost certainly more privileged than most: I was surrounded by them, and constantly shown love by them. When I had a meltdown upon a very teenage, very drunken discovery that I was gay, it was older queer women who hasted to remind me that this was great — I had a huge statistical advantage regarding orgasmic frequency ahead of me.

Though I’ve complained about the initial dissapointment of uni, I only felt that way because I’d developed a certain confidence in my sexuality by then, including the idealised belief that the whole world was gay like me.

Hearing lesbians a little older than me talk about crushes, sexual encounters, and girlfriends with an actualised confidence altered the way I thought about myself. Not in a grand, immediately identity shifting way, but in the way that stopped me from policing my little gay thoughts.

I hope that articles like this hit the top of “am I a lesbian” Google search functions, and serve the same function these women did for someone else like me.