For as long as we have talked about social justice, advocates for change have called on empathy to improve the way we treat each other. One method for eliciting empathy is an appeal to understanding, summed up neatly in To Kill A Mockingbird: “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view… until you climb in his skin and walk around in it.”

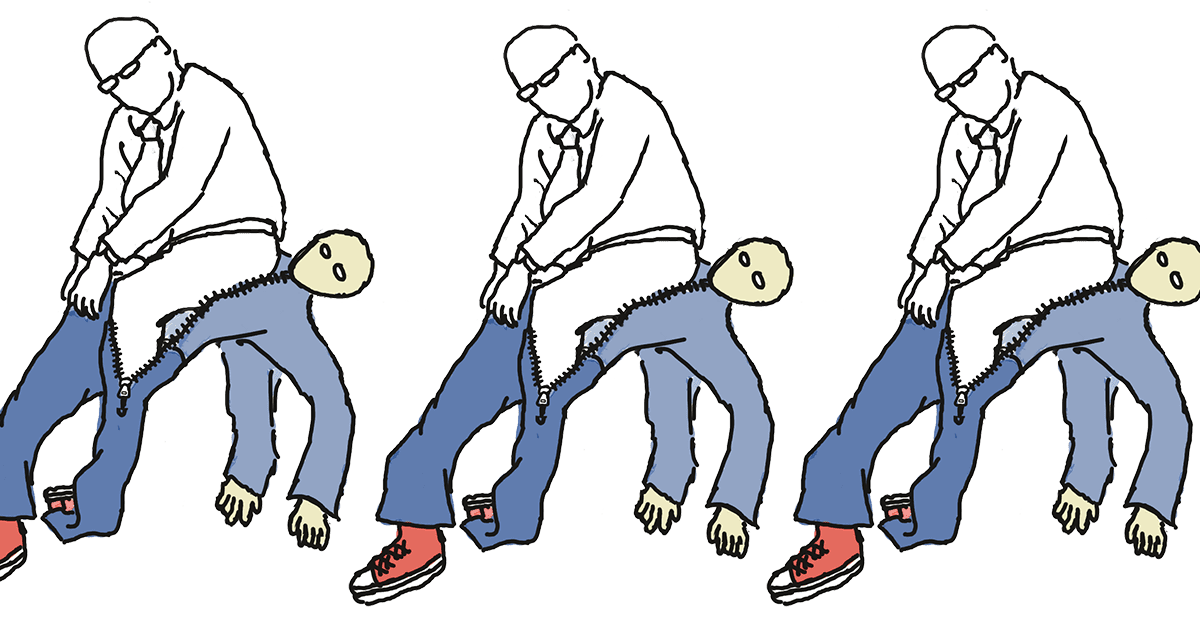

Although the thoughtfulness of putting yourself in someone else’s position can be useful, it is a fallacious basis for many arguments relating to identity politics. It can lead to inquisitive discussions being undermined and sidetracked unnecessarily. ‘Role reversal’, i.e. The rhetoric of imagining yourself in the shoes of someone else, as a persuasive strategy can be flawed and unhelpful, and offers an inefficient way of debating important issues.

The argument of role-reversal is often used to highlight how if another person was subjected to the same treatment as an (often marginalised) individual, their treatment would be considered unacceptable. Although this approach barely captures most salient forms of oppression, it would be remiss of me to ignore that sometimes highlighting those obvious forms of oppression is important. For example, men often have their experiences of abuse dismissed because there is a cultural expectation that they are the perpetrators, not victims, of domestic and sexual violence. Identifying that if the behaviour a man faced was experienced by a woman, it would be labelled abuse, can be a compelling way of proving that that man is experiencing harm. If it takes reversing roles to realise that a problem exists, then exercise is probably worth it.

However, in most contexts that I have seen the argument used in, it fails to prove that a harm exists. Instead, it is an attempt to intensify or mitigate the extent of a harm that someone is experiencing based on how much the listener of the analogy would be harmed. This is problematic for two reasons:

Firstly, asking someone to reverse roles between the historically oppressed and historical oppressors has an incurable asymmetry which invalidates it as a thought exercise. Both parties start from such different starting points that the swap will not remedy their differences, rather pretend that they do not exist.

For example, if a black comedian makes jokes about white people, they may be met with the criticism —)“if a white person made jokes about a black person, that would be racist!” The mistake made by said critic is considering the joke in a vacuum. Perhaps, if someone from racial group A is racist for making fun of someone from racial group B, it stands to reason that the inverse would also be true. However, we are not talking about groups A and B. We are talking about black and white people.

Black people, who had dehumanising caricatures made of them in minstrel shows for white people’s entertainment, stereotyped as brutish and violent by white people and had that used as an excuse to be overly punitive towards them in cotton plantations, lynch mobs, police forces and prison systems today. They were also labelled “ghetto” and uneducated by the white landlords and politicians who continue to deny them access to quality education and living conditions. Jokes made about black people based on unflattering stereotypes are a tool of oppression used to normalise and concretise racism and its deadly consequences. The same simply is not true for jokes at white people’s expense. ‘Reversing roles’ is a pointless exercise.

This same problem occurs even when the speaker aims to support, not undermine, the people whose experiences they analogise. The hypothetical of “what if people refused to call you by your preferred name?” to make deadnaming intellectually accessible to cisgender people is insufficient. I am quite often referred to by the wrong name — people often misremember ‘Nicola’ as ‘Nicole’ — but I often do not bother correcting people. It doesn’t matter that much to me if people make mistakes with my name – it is just a name, and usually, the mistake indicates no lack of respect for me. Deadnaming a trans person is fundamentally different; a preferred name holds a great deal of personal significance as it not only represents the autonomy to choose one’s name, but reaffirms the trans person’s right to exist as they prefer. A trans person has every right to react with more distress to being deadnamed than I do to being called by the wrong name precisely because of how different the context of those interactions are.

Role-reversal strips incidents like this of their context. It forces people from marginalised groups to filter their experiences through a frame of privilege. This is politically and discursively dangerous: when arguing for equity, reducing the experiences of marginalised communities to injustice in a vacuum undermines how profoundly necessary reparations may be. It is deeply insulting to force someone to justify the pain they are feeling by pointing out how bad it would be if someone else felt that pain. To return to Atticus’ metaphor, people shouldn’t have to remove their own skin to give you a go walking around in it.

This leads to the second issue: empathy based on familiarity is a poor resource for compassion. Although putting yourself in someone else’s metaphoric shoes is an intuitive way of eliciting compassion (if you do not like being treated a certain way, others likely won’t either), it is not a comprehensive one. Some people’s “skins” will not fit you, no matter how hard you try. Whether separated by geographic distance, large age gaps, or vastly different socioeconomic statuses, some people’s life experiences will be simply unimaginable to you. I know nothing about how it would feel to be raised as a black person in poverty in Brazil, as a trans Muslim person in Indonesia, as an ultra conservative Christian in the American South. If my compassion only extends so far as what is familiar to me, it would suggest that I ought have no empathy for those whose experiences I cannot relate to. Basing compassion on proximity builds protectionism and exclusion. It isolates those who are already marginalised. It stagnates social change. Meaningful change necessitates reaching across the gaps entrenched in the status quo and extending care to those whose “skins” you cannot walk around in.

Discourse about social justice is important. Changing people’s minds impacts the way they treat others, the businesses they purchase from, the way they vote. It is important that this kind of change is meaningful. When calling for support for a cause or a community, let’s think beyond the hypothetical scenarios. Rather, stress how every human being – regardless of how similar they are to you – deserves dignity, and how they may suffer indignities that you may never experience. Care about people from the skin you already wear.