For as long as so-called Australia has existed, this colony has been a crime scene and it has inflicted a genocide on my people. Not only a genocide in the conventional sense – measured in corpses and lives lost – but a cultural genocide too, evident in the erasure of our languages and of our songlines. Nowhere else in the world has the ferociousness of the commitment to strip us of everything that sustains us been so consistent.

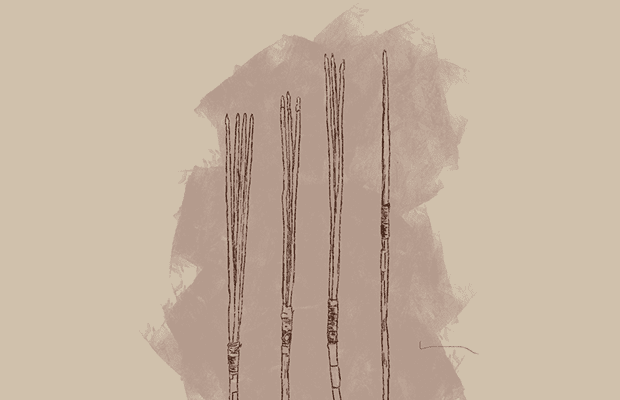

Epitomising this pattern, which plagues the historical relationship between First Nations people and the settler-state, is the plight of the Kamay spears – forty fishing spears stolen from the Gweagal people in a brutal opening salvo to Britain’s colonisation of Australia.

Since their theft in 1770, the spears were held in Cambridge University’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology at the behest of Trinity College. Last year, the spears were brought back to Gadigal land for the first time in more than 250 years as part of an exhibition at the University of Sydney’s Chau Chak Wing Museum. When I first reported on the spears, this signalled for the local Indigenous community, particularly members of the La Perouse Aboriginal Land Council, the possibility of repatriation – that is, the return of the Kamay spears to the Gweagal people.

However, in a move emblematic of colonial paternalism which dictates the terms of access and control over important cultural artefacts for First Nations people, the spears were returned to Cambridge University in July 2022. This affirmed to the local Indigenous community what we have always known – that every time we go to drink from the well, we are drowned. This pattern can be traced throughout the historical relationship between First Nations people and the settler-state. In 1967 we were allowed to be counted as humans, but had laws made for us that treated us like dogs. The promise of Mabo never eventuated with land rights of effective Native Title legislation. In 2008, Kevin Rudd delivered the National Apology to the Stolen Generations while rolling out the Northern Territory Intervention. Even now, we are embroiled in debate around symbolic constitutional recognition while a humanitarian crisis is occurring in the town camps of Alice Springs. Each time we are lured into the light, we are mugged by the darkness of this country’s history. Any progress we seek is unconditionally reliant on the government acting in good faith – something which they have never been capable of doing.

While the delineation of museums as nothing other than engines of colonial theft, trickery and violence may appear to be bland and stubborn, they are inextricably tied to the genocide of First Nations communities and are irredeemable essences of empire. A 2018 report commissioned by French president Emmanuel Macron, for example, found that over 90% of all Africa’s cultural heritage was held outside Africa by major museums, which have sprawling collections of “essentially stolen goods”. This characterisation is upheld by the behaviour and attitudes of institutions like the Chau Chak Wing Museum and Cambridge’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology – which at best demonstrate a misunderstanding, and at worst exhibit a wilful ignorance, of the deep spiritual and historical ties between First Nations communities and their cultural artefacts. The Kamay spears were used for fishing. Under the Gweagal’s system of kinship, communal hunting practices were crucial to the survival of their communities. When Cook seized the spears in 1770, he wasn’t just stealing a bundle of sharpened sticks – he was, in a very literal sense, stealing the vitality and the lifeblood of the Gweagal people.

While museums typically sermonise their importance as bastions of history and knowledge, and argue that objects of historical importance must be cared for by professionals, we know now that important artefacts are safer in the hands of Indigenous communities than they are in cultural institutions. The Elgin Marbles, taken from Greece and held in the British Museum, were permanently damaged during “routine maintenance” in the 1930s, where they were scrubbed with wire brushes and “a harsh cleaning agent”.

It’s for these reasons that Trinity College’s recent decision to return the remaining Kamay spears to the Gweagal people is a welcome one. Chairperson of La Perouse Local Aboriginal Land Council Noleen Timbery said the decision to repatriate the spears was the culmination of “patient” discussions between Trinity College and the Gweagal community.

“It’s something that we’ve worked at and it’s something that we’ve been talking about for a really long time,” Timbery said.

Ultimately, the Kamay spears deserve to be held and cared for by the descendants of the people who made them. Cultural inheritance – that is what is at stake.

Ray Ingrey, Dharawal man and chair of the Gujaga Foundation, said the story of the spears was part of the wider stories told by generations of his Elders, but that their return was bittersweet as many are not alive to see them come home.

“Our old people always spoke about it. It wasn’t set by our generation, it was set by those old Dharawal people, and in particular women. I think they’d be looking down on us proud of what we’ve achieved today,” said Ingrey.

The return of the spears back to Country still needs to be formally approved in the UK by the Charity Commission to allow Trinity College to grant legal ownership to the La Perouse Aboriginal Land Council and the Gujaga Foundation after their request for repatriation.

Once formal approval is given, the spears will return to Australia within the next few months to be cared for by institutions here. After further community consultation by the La Perouse community, they are expected to have a permanent home at the planned visitor centre to be built in Kurnell, near Botany Bay.