Oscars season has come and gone. The past year has been a fruitful era for African-American films, with Black Panther, If Beale Street Could Talk, The Hate U Give, and many more achieving financial and critical success. Out of the ten Best Picture nominations at the 2019 Academy Awards, three featured African-American narratives. But despite what has been a successful year for black cinema, Peter Farrelly’s Green Book, a film whose tone departs from Farrelly’s previous portfolio in Dumb and Dumber and was a strong contender for the Best Picture and Best Original Screenplay award, remains mired in controversy.

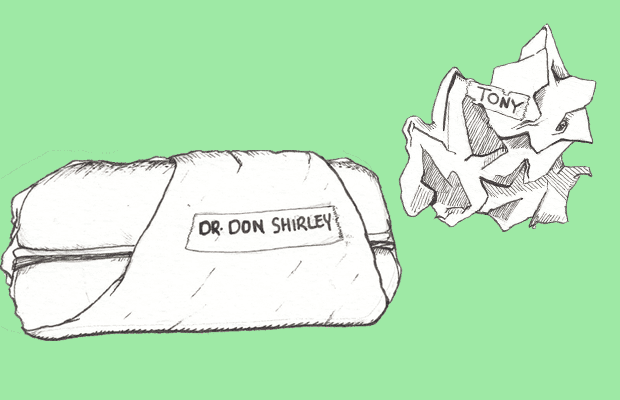

Green Book depicts the relationship between Dr Don Shirley (Mahershala Ali), the acclaimed African-American pianist and Tony Vallelonga (Viggo Mortensen), his Italian-American driver and bodyguard. Their friendship solidifies as they experience several incidents caused by the infliction of racism, segregation and indignity.

Despite its release only a month ago, Green Book follows a familiar script. As Shirley and Vallelonga make their way through America’s Deep South of the 1960s, they follow in the tried-and-tested footsteps of a long lineage of films in the genre of ‘feel-good race relations’ alongside other films like The Help and Hidden Figures. Films of this genre have been subject to common criticism — they lack nuance, oversimplify complex racial dynamics and essentialise characters into stereotypes. Even Farrelly’s exploration of the interplay between Shirley’s sexual orientation and his racial identity is little more than a plot device, lasting two scenes and skimmed over for the rest of the movie. But despite the feedback received by these films, they are frequently and continuously accepted by mainstream organisations like the Academy and its oft-discussed preference for placatory rather than confrontational films on social problems.

The Academy’s support for Green Book, no matter how well-intentioned, comes at a cost. Conferring Green Book contender status for Best Picture provides it with social capital and magnified public attention at the expense of acknowledging a more diverse range of African-American films which emerged in the past year.

Sorry to Bother You, written and directed by hip-hop-artist-turned-director Boots Riley, depicts the story of Cash, a black telemarketer, who rises through the ranks at work by using his ‘white voice’ over the phone, and in doing so, unravels a corporate conspiracy of modern-day slave labour. David Cross voices Cash’s ‘white voice’ and Tessa Thompson wears outlandish earrings with antisocial captions, all within a realm of extreme satire and science-fiction absurdity. While by no means perfect, Sorry to Bother You gives audiences an intersectional representation of racial issues, appropriately tailored to our current social consciousness and race’s entanglement with capitalism, classism and gender.

Sorry is symptomatic of a new wave of independent black films, some following in the wake of Moonlight’s Best Picture win at the 2016 Oscars. Through a rapidly growing quantity of films in African-American cinema, the breadth of films being produced has also concurrently expanded in variety. The increasing range of creative approaches to the African-American experience has allowed films like Sorry to provide an interrogative depiction of enduring racial tensions. On the other hand, the 1960s setting of Green Book erases any sense of immediacy or urgency in its depicted struggles of racial identity and resistance, reducing race issues into a relic of past times.

The growing force of African-American films is made invisible through the prioritisation of films such as Green Book, whose easy-going nature creates a comfortable option for the film industry. Studios have conventionally underrepresented African-American films due to the mistaken idea that “black films don’t travel” — an industry myth that African-American narratives don’t perform in global markets, making them supposedly less financially viable. Disappointingly, as a result, the amount of attention that the industry is willing to allocate to African-American film is limited. Within this zero-sum game, conventional, accessible and pacifying narratives prevail.

Despite the fact that two of the past five Best Picture winners have been African-American films, Green Book continues a pattern that is yet to be broken. By equating Green Book to Black Panther and Blackkklansman, which represent a new generation of black films, the film industry actively rejects a novel, dynamic definition of what African-American films can be. Instead, the construction of its own Academy-endorsed narrative is favoured, packaged for the emotional comfort of the highest number of audiences. One Academy voter told the New York Times that he would vote for Green Book because he was “tired of being told what movies to like and not to like,” a testament to the regressive nature of his support for the film.

While this is disheartening, African-American cinema has undeniably flourished and grown in recent years. But this trajectory can only develop if we can avoid overlooking the Sorrys of the future for the Green Books that will inevitably arrive. In doing so, it becomes possible to avert the risk of stagnating in the satisfaction of films with yesterday’s relevance, which now have little to say.