The Art Gallery of NSW has announced Sydney-based artist Claus Stangl as the winner of the 2022 Archibald Packing Room Prize, as well as the finalists of the Archibald, Wynne & Sulman prizes (AWS). Stangl’s work Taika Waititi was announced as the 2022 winner of the Packing Room Prize, with his portrait of the titular Aotearoa New Zealand filmmaker, actor and comedian, taking out the coveted award.

This year’s AWS Prizes received 1908 entries, almost 70 per cent being from NSW-based artists. An equal number of men and women entrants was reflected in the nearly even gender split of Archibald finalists (58 man and 54 women), alongside one non-binary finalist. The Sulman prize this year saw the highest known number of Indigenous finalists (6 of 29), whilst the majority of Wynne Prize finalists were women.

Notable Archibald winners of recent years include the 2013 and 2008 two-time winner Del Kathryn Barton for her works hugo and You are what is most beautiful about me, Ben Quilty’s winning 2011 work Margaret Olley, and 2022 finalist Vincent Namatjira’s winning 2020 work Stand strong for who you are.

The Archibald regularly consists of celebrity-subjects; the portrait prize finalists tend to be rather star-studded with sitters who have often made social or political waves in the previous year. It is worthwhile to consider that celebrity or recognisable portrait sitters are central to the public appeal of the exhibition. As one of the largest art and portraiture prizes in the country, the AWS perhaps cannot afford to alienate viewers with unknown or conspicuously controversial finalists. However, there is also an argument to be made that portraiture is highly engaging to a wide audience — regardless of the sitter — because it is able to capture the immaterial nature of someone’s being and their recognisable humanity in an alluring way.

Celebrities and cultural personalities who are sitters in this year’s Archibald include Hugh Jackman, Laura Tingle, Dylan Alcott, Peter Garrett and Deborah Conway.

Honi was eagerly expecting the 2022 AWS to deliver works reflective of the current socio-political climate both globally and in Australia. Undeniably, the past couple of years have seen some of the greatest challenges facing humanity in recent decades — what, if not the nation’s largest art competition, is better situated to display this?

As the country emerges into its ‘post-COVID new normal,’ it also emerges into a swathe of further crises. Considering the growing threat of climate change — as evidenced by the severity of the Lismore floods — and the impending crossroads of the Federal Election, the AWS 2022 was set to deliver a range of critical and politicised works. But did it deliver on this expectation? Here, Honi has gathered some of the exhibition’s most overtly political works to assess their message and role within the oft-celebritized collection of finalists.

The Archibald Finalists

This year, there are 52 Archibald finalists out of 816 entries and 27 per cent are first-time finalists — a surprisingly low figure, suggestive of barriers to breaking into the coveted pool of finalists. This may reflect a range of barriers to entry for new artists: whether economic or the founded in Prize’s requirements for a sitter of status: ‘preferentially of some man or woman distinguished in arts, letters, science or politics’.

This year’s most overtly political sitter is found in Joanna Braithwaite’s stunning large-scale portrait of the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) Secretary Sally McManus. An appropriately election-relevant piece, the portrait depicts the prominent union figure in a suit made of newspaper headlines referring to her work — various Murdoch rags stitched together and worn proudly. In regards to her choice of subject, Braithwaite chose McManus “because I was impressed by her unwavering pursuit of fairness, and the way she is unafraid to fight for what she believes in – gender equality, fair pay and workers’ rights, with the focus of uniting people for the common good.”

Close up of Joanna Braithwaite’s McManusstan.

Another significant finalist is Mostafa Azimitabar and his work KNS088 (self-portrait). The work was created using the only tools available to Azimitabar while held as a refugee in detention for over eight years on Manus Island and Melbourne hotels: coffee and acrylic paint applied with a toothbrush. The Kurdish artist was only freed on 21 January of this year, “On Manus Island, I was surrounded by chaos and trauma. Art helped me find tranquillity,” he said of his work.

The captivating self-portrait embodies the lived suffering experienced by Azimitabar, while also being emblematic of every refugee who has suffered under the cruelty of consecutive Australian governments. Staring down the viewer, the artwork exudes defiance and resilience. While the brown, dripping background is evocative of the dark struggles in his past, the vibrant rainbow of colours which build his facial structures reflect a hopeful outlook. Symbolically, the work is a painterly indictment on the dehumanising treatment of refugees across the world — “I chose the title KNS088 because for eight years I was called by this number instead of a name,” said Azimitabar

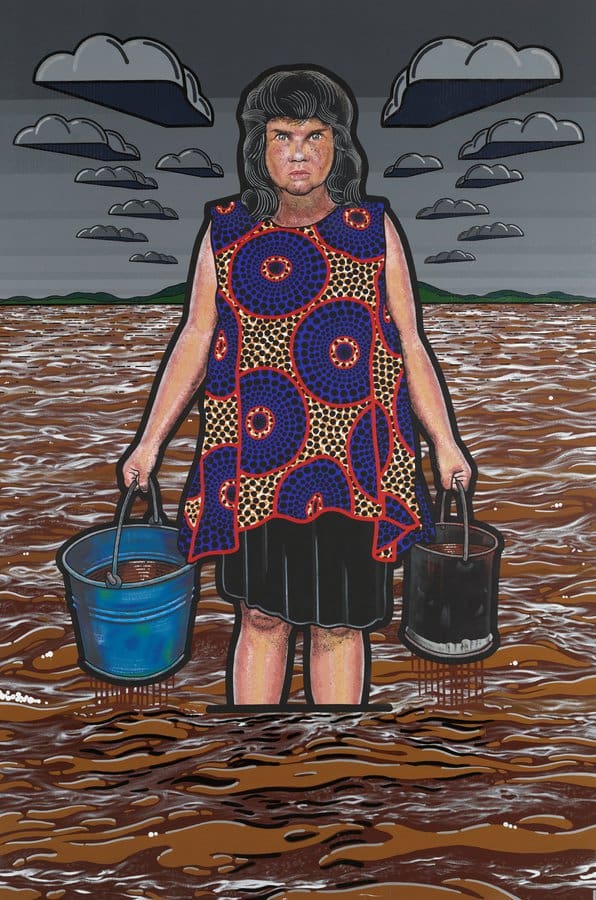

Further engaging with the political is Blak Douglas’ finalist work entitled Moby Dickens — the largest in the AWS, the portrait stands three metres tall and two wide. The work deals with the catastrophic impact of the repeated flooding of Lismore over the past months: “…another natural disaster in a country where the government refuses to take responsibility and act on climate change,” The four-time Archibald finalist explained to The Sydney Morning Herald in regard to her work.

Viewers wouldn’t be blamed for forgetting that a number of works for the Archibald prize have been created either in or around rolling COVID-19 lockdowns and restrictions across the country. Jonathan Dalton’s Day 77 is seemingly the only finalist to directly reference Australia’s collective time in isolation, with the title itself referencing the numerical day of lockdown the portrait was first drafted — a day that was also Dalton’s birthday..

The work itself is composed of three figures in their living room — Dalton, his wife, and one of their daughters. Dalton’s style of painting his subjects in intimate domestic settings has translated well to a self-portrait, with the vast negative spaces of the work emphasising their isolation. 2022 marks Dalton’s sixth consecutive year as an Archibald finalist.

A particularly striking finalist work is Jordan Richardson’s Venus, in which the artist has appropriated and reinterpreted Diego Velázquez’s 17th-century Rokeby Venus, replacing the goddess of beauty with writer, broadcaster, and serial-tweeter Benjamin Law. The subversion of Velázquez’s work brings up questions around beauty, gender and race while maintaining what Richardson describes as “a good deal of Benjamin’s humour embedded in the work”.

“I also believe it to be a sincerely beautiful picture. I love the voyeuristic nature of the pose, where, after closer inspection, we see him staring back at us through the mirror, watching us all along,” explains Richardson.

Whilst 2021 was the centenary of the Archibald Prize, 2022 is the tenth year of the Young Archies, open to entrants 5-18 years. The competition is judged on ‘merit and originality’ across four age brackets. This year has seen a record number of entries surpassing 2400, with 70 finalists exhibited at AGNSW.

The Packing Room Prize

The Packing Room Prize is selected not by a panel of judges or a board, but by the Art Gallery staff who receive and unpack Archibald submissions. With Head Packer Brett Cuthbertson holding 52% of the vote, it tends to reflect his own interest in realist portraits of popular celebrities.

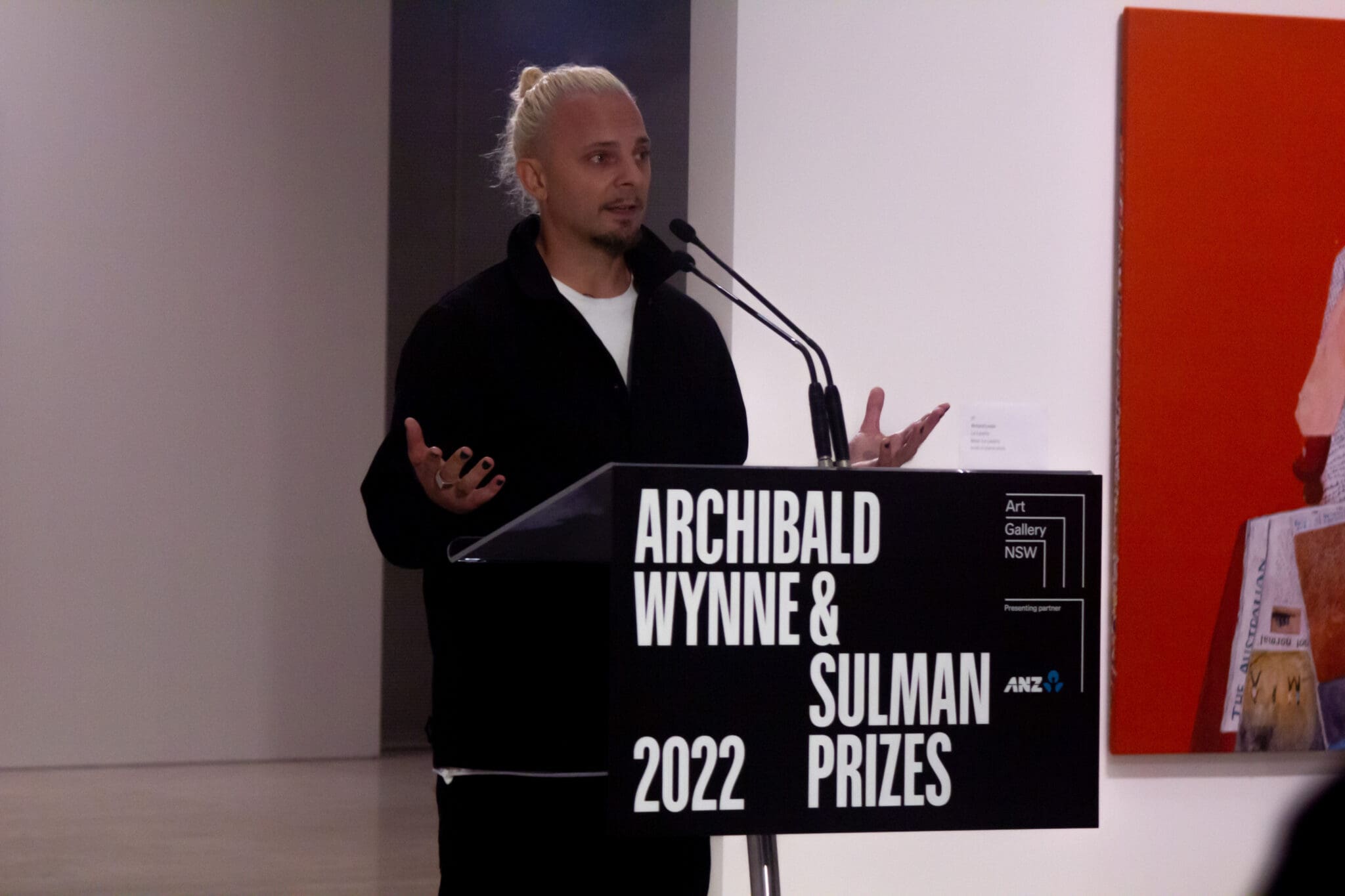

This year’s Packing Room Prize along with its $100,000 reward was awarded to Claus Stangl, self-taught artist and second-time Archibald finalist, for his portrait of Taika Waititi. Somewhat amusingly, Honi successfully predicted Stangl as the Packing Room Prize recipient while waiting for the media preview to begin.

Stangl thanked the Gallery and the Packing Room team for the award, “as an emerging artist it’s a massive honour to share wall space with some of my favourite Aussie artists.” He also thanked Taika for sitting for the portrait, “I really couldn’t believe it when he said I could paint him.” The sitting took place while Waititi was in Sydney to film Thor: Love and Thunder.

“I’ve really loved his work for years, it’s the light in the dark and it’s the levity that we often need.”

The artwork itself is painted in an anaglyph 3D-style, with slightly shifted blue and red versions of the subject extending from either side. “I wanted to create a portrait that captured Taika’s sense of humour and to execute it in a playful cinematic style, reminiscent of the movies of the seventies and eighties that were popular when he was a child,” said Stangl

“Painting in 3D-style was the hardest thing I have ever painted, because there’s two of everything, two of each pupil, two noses, everything shifted. But I learnt so much and it was worth it.”

The Packing Room Prize was established in 1991 by Brett Cuthbertson alongside former Head Packer Steve Peters. Cuthbertson says that the prize “started as a joke” after a reporter asked the pair who they thought would win the Archibald, and they pointed to a portrait of Labor MP Gareth Evans – ‘Well, we reckon this is the best one.’ Newspapers then reported that very portrait as having received ‘The Packer’s Prize’, and the Gallery went on to make the prize official the next year. Sitters for recent winners include Kate Ceberano, Meyne Wyatt and Jimmy Barnes.

Cuthbertson also used the Prize announcement to announce his own retirement after working at the Gallery for 41 years.

Cuthbertson spoke to how much he has enjoyed his many years at AGNSW, saying that one of the things he will most miss about working at the Gallery is the annual drop-off of artworks for the AWS Prizes. “It’s the people, the artists,” he said. “I love it. And there’s the whole parade of them bringing the works in, and seeing them again every year… It’s like a big family get-together.”

“I just love the place. It’s just unlike any other job.”

Cuthbertson has held the position of Head Packer for the past five years. His replacement for the position is yet to be announced.

The Wynne Prize Finalists

This year the Wynne Prize had 601 entry submissions and 34 finalists, half of whom were first time finalists and 18 of whom were First Nations artists. The $50,000 prize is the oldest art prize in Australia, established in 1897 following a bequest from Richard Wynne, it is dedicated to watercolour or oil paint landscape artworks of Australian scenery and figurative sculpture.

Indigenous, Torres Strait Islander and First Nations artists were at the fore of the prize exhibition this year, following in the footsteps of last year’s winner entitled Garak – night sky by Nyapanyapa Yunupingu. In recent years, nearly half of all finalists of the Wynne Prize have been by First Nations artists — notably, every winner since 2016 has been made by First Nations artist or collective. It is gratifying to see Indigenous artistic methodologies and means of representing Eora landscapes being given this platform; in a prize whose winners of its early decades consisted exclusively of rolling colonial hills and Western depictions of bushland.

On display, and catching Honi’s eye, this year are Aboriginal artist Betty Muffler’s work Ngangkari Ngura (Healing Country) and Winga (tidal movement/waves) by Alison Puruntatameri. Muffler’s work is representative of ‘ngangkari’ (traditional healing practices) which take place on Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara lands in South Australia, depicting the life-supporting watering holes within. Further, Puruntatameri’s artwork considers surging tidal waters on the Tiwi Islands, which are a part of the Northern Territory.

Continuing these thematics and dealing with issues of waterways, Geoff Harvey’s watercolour work Lismore flood 2022 was an impactful addition to the prize exhibition. His own home washed away by the floodwaters, the artwork springs off the canvas in warming tones conveying both catharsis and anger.

Lastly, threads of climate in crisis continued to permeate the prize exhibition through Franklin River Valley, Iutruwita/Tasmania (topographic relief) by Wona Bae and Charlie Lawler. The work is a standout sculptural form of the prize; the circular sculpture is a relief carving composed of charcoal segments. Serving as an abstract topographic map of the Franklin River area, Bae and Lawler’s work is a homage to the cite’s history of environmental activism and protest. In 1982 over 10,000 people protested the proposal of a hydro-electricity generating dam in the river and parklands, making the campaign one of Australia’s largest environmental movements.

It is particularly interesting that the work is made out of coal and is a criticism of climate change and environmental disaster — catalysed precieley by coal and the fossil fuel industry. “This work seeks to find balance and harmony in a time of increased environmental vulnerability in the face of human-induced climate change” the artistic pair said.

Evidently, the Wynne Prize exhibition is well worth viewing. With several large-scale works that represent the plight and resilience of our environments, and in a time when we are seeing the tangible impact of climate change, the 2022 finalists are a stunning collection of visual works with a political slant.

The Sulman Prize finalists

The Sulman Prize is centred around genre and subject painting or a mural work, with an award of $40,000 for the winner. First awarded in 1936, each year the trustees of AGNSW select a guest artist to judge the finalists — this year’s judge is 2021 Archibald finalist, Joan Ross. Generally seeing the more abstract and modern styles of art, the Sulman Prize is a glistening juxtaposition to the works in the other prize exhibitions which regularly lean into hyperreal painterly styles. This year’s collection of finalists did not disappoint.

Three works which embody the contemporary vibrancy of the Sulman Prize are Victoria Atkinson’s Angel Mum Noel Humphrey, Wendy Sharpe’s Witches with green light and Sophie Victoria’s three-dimensional work The Spectacle. Though vastly different in use and technique, both Atkinson and Sharpe’s works feature bright swathes of neon colours and abstracted forms. Atkinson’s acrylic and LED work embodies her mother and Sharpe depicts interpretations of witches from Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

The Spectacle, however, takes a sculptural turn, with its cellophane-like iridescent surface creating different surfaces and colours as viewers move around the work. Victoria refers to this effect as ‘a theatrical play of light’ that plays out in the gallery space. The Spectacle is made up of multiple layers of filters and reflective surfaces, which alongside its titular reference to Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle, acts as a reflection on an image-obsessed consumer culture.

A work that delves into an interesting historical subject is Leslie Rice’s Blaming me is blaming God (a picture of Joseph Merrick). Merrick suffered from severe deformities (now considered to be Proteus syndrome) to his face and skull. Living in the late 19th century, he endured social alienation and a short-lived career in 1883 as a ‘freak’ at a freakshow. Rice’s dark and ominous painting is acrylic on black velvet fabric — a totally unique approach which creates an apparition-like, glowing-yet-hazy appearance of the subject that any Dutch Golden Age painter would be envious of. Upon viewing the work I wonder ‘what would Rembrandt think?’ Honi loves this piece and the ways in which it makes your eyes work; it demands to be seen and appreciated in person.

***

Despite the celebrity status and media circus that surrounds the AWS Prizes, the exhibition is well worth seeing in its own right. Each prize has a wealth of works to be viewed and talked about, from the avant-garde Sulman to the beautiful depth of the Wynne landscapes and sculptures, and of course the ever-present and engaging Archibald Prize finalists.

Finalist works of the Archibald, Wynne, and Sulman Prizes will be exhibited at the Art Gallery of New South Wales from 14 May to 28 August. An alternative selection of Archibald Prize works will be exhibited at SH Ervin Gallery as part of the Salon des Refusés from 14 May to 24 July.

The winner of the 2022 Archibald Prize will be announced this Friday 13 May.