The laboratory is a strange place. Even after all the burners have been turned off and benchtops wiped clean, the scientists and technicians have left for the night, reactions are often left to proceed overnight and cells are left to divide in their dishes.

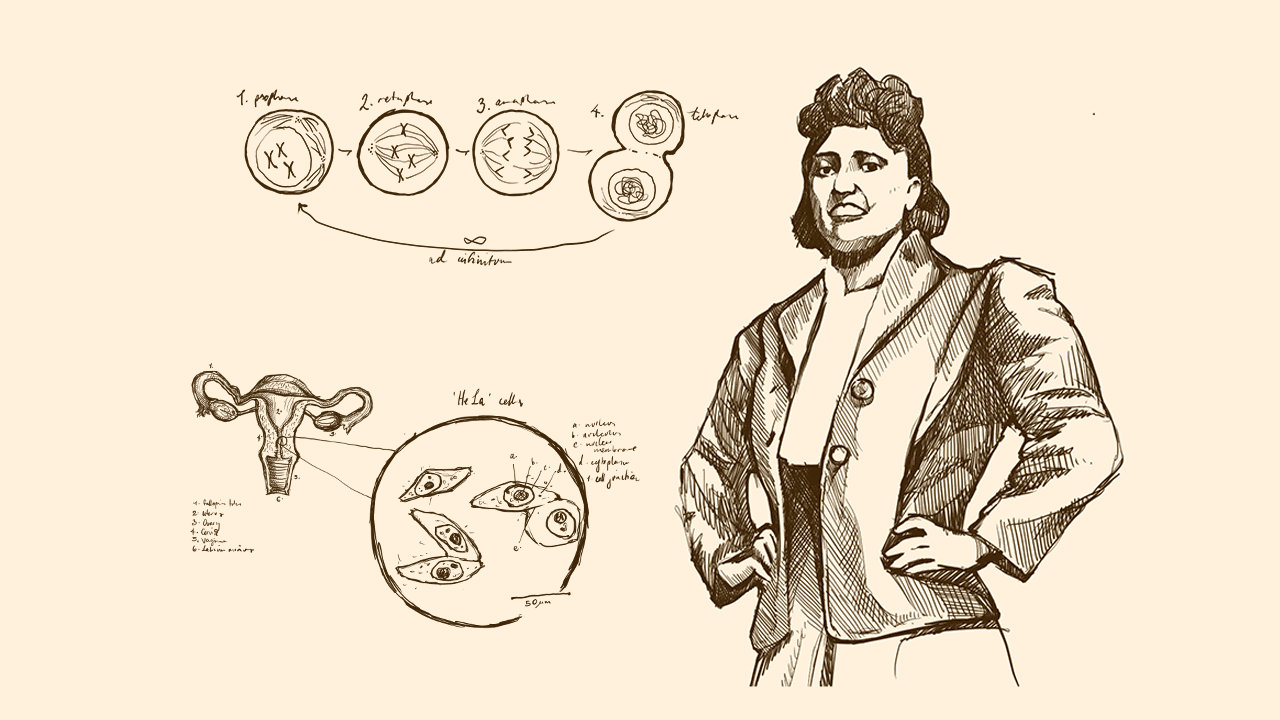

In many labs, you will find vials marked with the four-letter code “HeLa”. This cell line has been used to further medical research in countless ways — it was even used in vaccine development during the COVID-19 pandemic. These cells were taken from Henrietta Lacks 72 years ago, without her permission.

Henrietta Lacks was a black woman who grew up on a tobacco farm in Clover, Virginia, under the care of her grandfather, Tommy Lacks. When she was twenty, she married her cousin, David ‘Day’ Lacks, in her preacher’s house. They moved to Baltimore when the steel industry boomed as the United States entered the Second World War, in pursuit of an easier life.

Henrietta Lacks continued to visit the tobacco plantation in Clover after the move, and her house was the centre of the Lacks extended family. She loved cooking, and would prepare enough food for anyone who walked through her door. She enjoyed going out dancing, and painting her nails red.

Remembering Henrietta Lacks, and locating her within the wider system of medical and structural inequality in America, is essential.

While bacterial cells are hardy and often have multiple mechanisms to ensure they can grow in adverse conditions, human cells are much less enduring. Cell biologists attempted to grow them outside the human body for years, but once isolated from the human organism samples would die off and fail to reproduce.

Cell growth must be carefully regulated to ensure that there are no errors in the genetic code. Humans have regulation built into every cellular process: every single product, from a protein to a new cell, must be made only under strict conditions. The unregulated division and mutation of cells is what we call cancer.

Beyond regulatory mechanisms that oversee all cellular processes, tumour-suppression genes exist as sentinels. They detect excess growth and subsequently induce death in the offending cell. Human Papillomavirus, or HPV, can transform cells. It produces proteins that disable these sentinel mechanisms, leading to cervical cancer.

Henrietta Lacks was experiencing discomfort after the birth of her fifth child. Upon examining herself, she discovered a sore near the opening of her cervix, within her vaginal canal. The local doctor thought it was a syphilis sore, but when she tested negative for Syphilis he suggested she visit the hospital.

Johns Hopkins Hospital, established in Baltimore from a charitable donation and aimed at treating the sick and poor, was the only hospital for miles that would treat Black patients. In 1951, when Henrietta Lacks first visited the hospital gynaecologist, Black patients were treated in segregated wards, and had to use separate bathrooms and water fountains.

Two samples were collected from Henrietta Lacks during her treatment: one from the growth near her cervix, and one from neighbouring regular tissue. These samples were passed on to Hopkin’s cell biologist, George Gey, who had a lab set up to attempt to grow human cells in vitro — outside of their tissue.

Once incubated in the lab, the cells from Henrietta’s tumour began to grow at an unprecedented rate. While the normal cells died after a few days, the cancerous cells persisted, and continued dividing exponentially. They became immortal — meaning that they weren’t subject to the typical processes that limit the number of times a cell can divide.

Cell biology labs have continued to use HeLa cells for decades. Henrietta Lacks’ unwitting donation has furthered science: once scientists could grow and visualise cells outside of the human body, they learnt a lot about cancer, polio, vaccines and even IVF. She has advanced medicine in so many fields — but she was never once consulted about it.

Henrietta Lacks did not consent to the collection of her tissue. She did not consent to the distribution of these cells among scientists across the globe. She did not consent to the release of her name, nor her medical records, nor the publication of her genome. Henrietta Lacks died in 1951, and her family did not know about the collection and use of her cells until 1975, when a journalist, Rebecca Skloot, contacted them for a story.

Despite birthing a wealth of scientific resources — notably the development of for-profit biotech companies — Henrietta Lacks’ family never received financial compensation for the harvest and continued use of her cervical cancer cells.

Despite the uncountable contributions of a Black woman, Black communities had some of the worst health outcomes in the crisis. Understanding Henrietta Lacks’ story requires a deeper analysis of the structural inequalities that underlie healthcare in America and beyond: she received substandard care in a segregated hospital for the poor, had her tissue harvested without consent, tissue which continues to be exploited to further the research of institutions that uphold structural racial inequity.