The campaign against the Voice has been driven by a racist preoccupation with denying First Nations people a presence in Australian society and the Constitution. This is the reason for which the Liberals and Nationals have never expressed support for the Voice proposal.

Does the Voice create inequality in an otherwise race-blind Constitution?

The Constitution which established Australia was already racially selective by expressly ignoring the existing custodianship of Indigenous peoples before European invasion. Its architects went to great lengths to assuage the guilt and discomfort of Australia’s fledgling colonies, yet said nothing of millennia of prior ownership.

The Constitution must be seen as an instrument of colonial rule, and its silence on Indigenous ownership was deliberate — an explicit act of legal and cultural deletion. Race was assumed to be white European and thus not explicit. Black Australia was dealt with by exclusion.

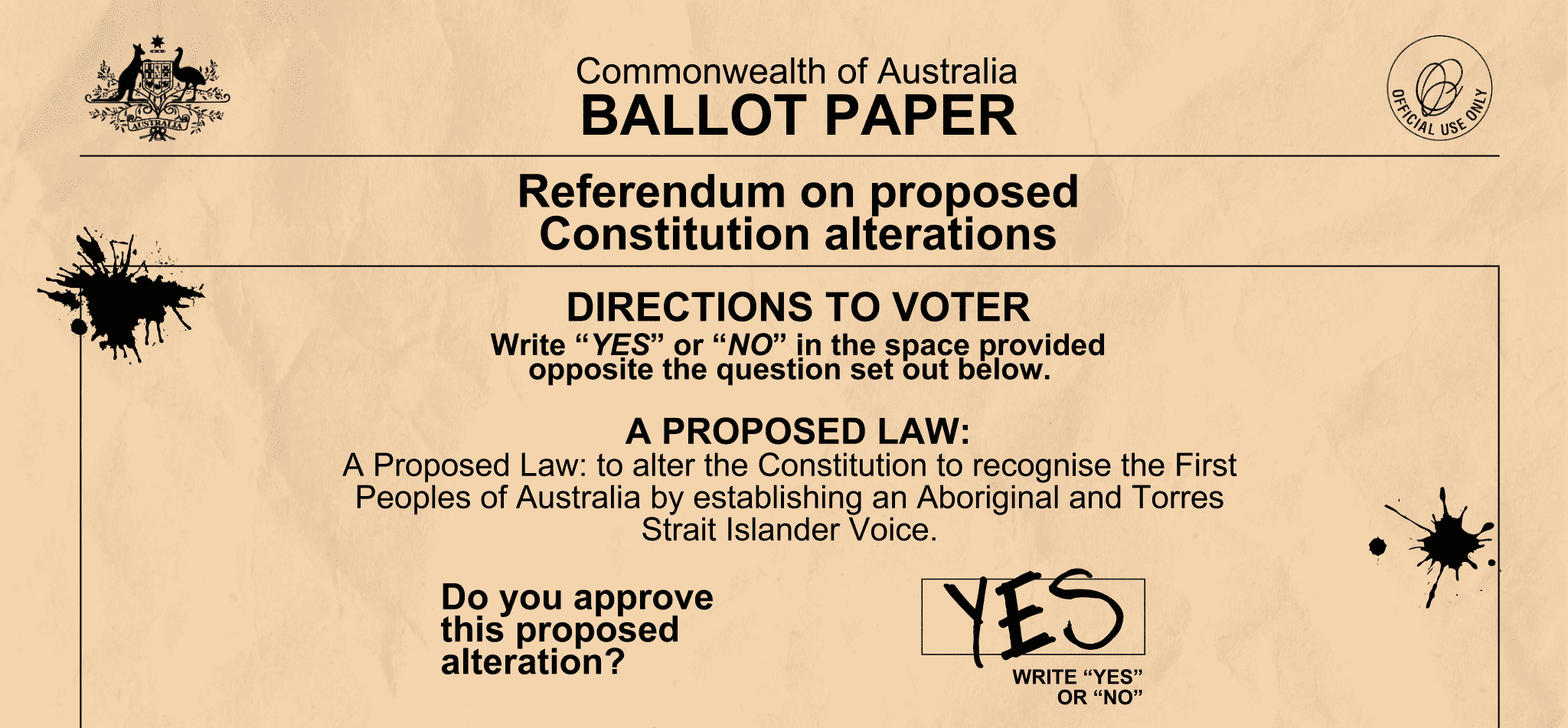

As such, the recognition of First Nations peoples — and the enshrinement of a Voice to Parliament — in the Constitution is a means by which the colonial logic of the Constitution, and its institutionalised disavowal of the existence of First Nations people can be partially remedied.

The Voice will afford First Nations people no additional “rights” compared to non-Indigenous people. This is not a positive. To herald the Voice’s lack of binding power is to acquiesce to the violent settler state, the system which stole these powers from First Nations people in the first place. Honi rejects this.

The Constitution should give First Nations people the powers to control, not just provide input into, decisions which affect them. Those rights are inherent within First Nations’ people’s historic and ongoing claim to sovereignty. It is greatly regrettable that the Voice doesn’t do this.

Will the Voice impact Indigenous sovereignty?

Among the most contested myths about the Voice is the question of sovereignty, and the claim that the Voice would force Indigenous people to surrender their sovereignty.

To challenge the claim that any constitutionally-enshrined Voice would extinguish First Nations sovereignty, it is crucial to first understand what sovereignty is.

As constitutional law expert Professor Anne Twomey explained to Honi, “sovereignty means different things to different people. For many Indigenous people, sovereignty is as much a moral or political concept as it is a legal one.”

Under international law, sovereignty refers to a sovereign state — one which has clearly defined borders and a permanent population, and one which exercises control over issues of law, immigration and trade.

It is generally accepted that sovereignty, in the legal sense, can be acquired either through cession, conquest or prescription of land deemed terra nullius. Although it is true that First Nations people never surrendered collective sovereignty over their land, there exists no legal framework for Indigenous people to exercise sovereignty in real terms.

Then, there is the more abstract, intangible definition of sovereignty — the right of Indigenous people to practise culture and exercise a spiritual relationship with their traditional lands and waters.

In a contemporary settler-colony such as Australia, First Nations people can only exercise a diluted version of sovereignty in the narrow political sense. In real terms, a constitutionally-enshrined Voice has the potential to enable greater exercise of sovereignty.

The Uluru Statement clearly stipulates that Indigenous sovereignty shall coexist with that of the Crown, and neither can be extinguished by a constitutional amendment.

It says: “Our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tribes were the first sovereign Nations of the Australian continent and its adjacent islands, and possessed it under our own laws and customs …

“This sovereignty is a spiritual notion: the ancestral tie between the land, or ‘mother nature’, and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who were born therefrom, remain attached thereto, and must one day return thither to be united with our ancestors. This link is the basis of the ownership of the soil, or better, of sovereignty. It has never been ceded or extinguished, and co-exists with the sovereignty of the Crown.”

All of this is to say that a constitutionally-enshrined Voice to Parliament has no legal power to impact sovereignty as it currently exists. This can only be done through a framework of very specific provisions during the Treaty process, and so it is a fallacy to claim that the Voice to Parliament would force Indigenous people to surrender sovereignty to the Crown.