In a recent Sydney Morning Herald story, Tim Biggs teaches readers all the tips and tricks to get books for cheap. Writing in the wake of e-retailer Book Depository’s closure, Biggs compares the prices of titles between Australia’s dominant online booksellers: the outgoing Book Depository, Amazon (Book Depository’s parent company), and Booktopia. Biggs cites a brand-new bestseller that, on Amazon and Booktopia, is advertised for almost half of its recommended retail price — he urges readers to go for it. He goes through the usual shipping loopholes, plugs Amazon Prime, and concludes his discussion of “competition” with no reference to any bookseller beyond the above online behemoths.

What Bigg’s article fails to realise is that when these online retailers so markedly discount books, they obliterate the chance for independent bookstores to survive. Biggs is by no means the sole culprit — the internet abounds with step-by-step guides to bookshopping “hacks” — but that being said, he brings fare that belongs on finder.com.au into a national masthead. To provide publicity for Amazon, a half-trillion-dollar conglomerate that has consistently disregarded human and worker rights since its inception, is to erase the damage that online mass-market booksellers bear on the Australian retail landscape.

According to a statement by BookPeople, the leading Australian booksellers’ association, Amazon has become Australia’s dominant retailer for the sale of books. Their position in the market allows them to offer such a deep discount on titles, particularly on the bestsellers that appeal most broadly to the Australian market. Books, for Amazon, are loss leaders: their revenue lies substantially in Amazon Web Services, and their business model is increasingly dependent on cloud infrastructure. Due to their capital, Amazon is then able to tilt Australia’s labour, tax and import laws in their favour — their success is contingent on their aggressive, legally contentious business strategies.

All of this is to the detriment of your local bookshop. In the wake of a pandemic that temporarily shut down brick-and-mortar retail, and amidst the rental, wage, and cost of living crisis that we face today, independent bookstores cannot compete with a corporation that discounts their fundamental product. Further, Amazon owns two of the other most damaging forces to independent bookstores, Kindle and Audible — if, in their shadow, bookstores cannot turn over a profit, what is their future?

I want to quote briefly from the author Charlotte Wood, and argue that “bookshops are the safety vaults for the seeds of our country’s cultural and intellectual life.”

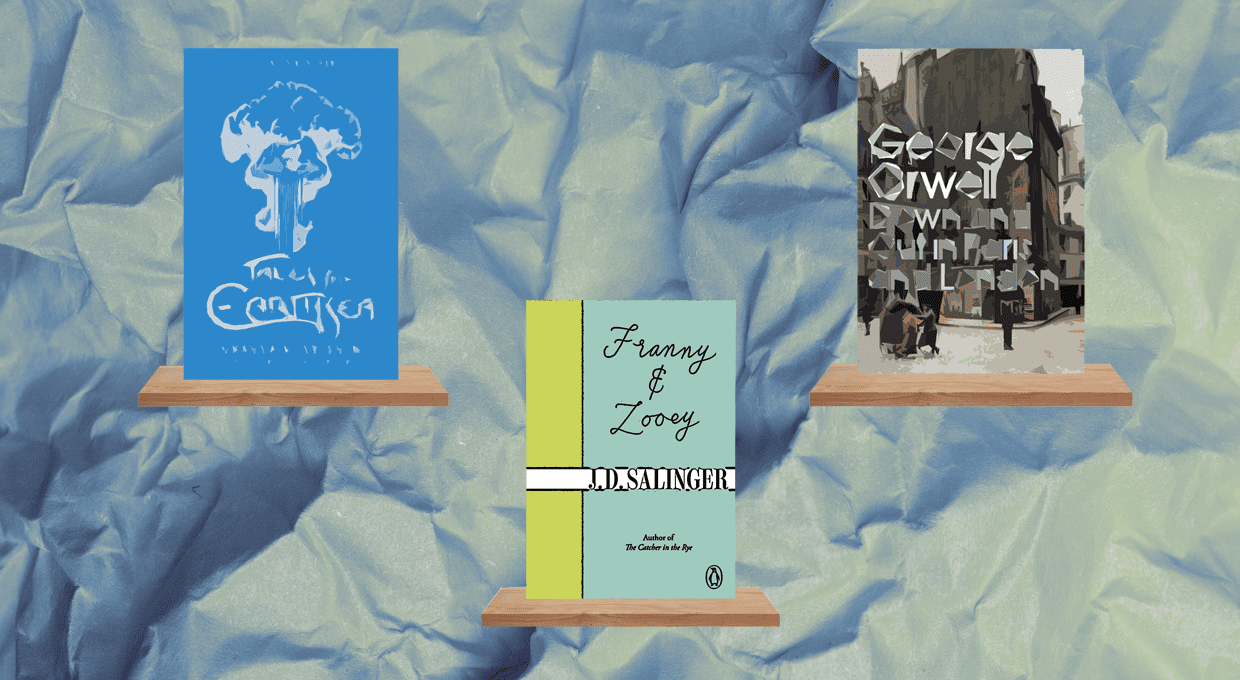

When independent bookstores are allowed to flourish, they can provide considered, personalised service to their customer base — the very same bookseller gave me Le Guin’s Earthsea at the age of ten, Salinger’s Franny and Zooey at the age of sixteen, and Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London just last week. Through physical bookstores, a love of reading is promoted: educational events are held, local authors represented, and a literary culture blossoms. In a broader sense, independent booksellers allow for retail variety: they cultivate a “bibliodiverse” landscape that discourages market hegemony, and encourages customer choice. Further, since bookstores tend not to depend on aggressive digital advertising, they can encourage the sale of culturally significant books, and titles that promote independent ideas and thought, over mass-market bestsellers. When they disseminate books from smaller publishers, bookstores encourage the discovery of unknown authors, whose works would otherwise be relegated to the depths of Amazon’s web pages. It is for this reason that the loss of Balmain’s Feminist Bookshop, Surry Hills’ Architect’s Bookshop and Published Art, and Beecroft’s Children’s Bookshop, is so devastating — bookshops that are curated, intimate and thoughtful are a net positive for local communities.

What, then, is the solution? I think we need to turn to France, where books are (rightfully) seen as cultural assets. Following the 1981 enactment of the Loi relative au prix du livre — more commonly known as the Lang Law, after the socialist Minister of Culture responsible for its creation — France has successfully protected small, traditional booksellers from chain retailers and mammoth Amazon-esque forces. The original premise of the regulation is that when a publisher decides on a book’s price, they are obliged to print it on the back: crucially, retailers are not permitted to sell the book for a discount of more than five per cent below this RRP. This “fixed book price” system, or FBP, preserves brick-and-mortar bookselling: France boasts over 3,500 independent bookstores, a number that continues to rise, while over the last decade, the number of bookstores in Australia has dropped by 65.5% (to 1,475 sites, inclusive of chain stores à la Dymocks and QBD). In recent years, France has extended the Lang Law to cover e-books and audiobooks, and even to curb Amazon’s free delivery deals. Similar laws exist across the world, notably in Germany’s Buchpreisbindung and Japan’s Resale Price Maintenance System, and serve to encourage balance, fair competition, and a flourishing culture of independent bookstores. When Amazon does not wield all control, the market is far better off.

Australia does not regulate book prices — neither, for that matter, does the U.S. or the U.K. — but we should. Prior to 1972, we did employ a fixed book price system: a growing desire for unimpeded free-market capitalism led to the law’s repeal. However, in our current climate, the need for fixed book prices in Australia has never been higher.

When we speak about saving bookshops, we are not talking about capital: we are speaking about ideas, politics, and culture, and to preserve this, books should not be commodities subject to competition-based pricing. Given Amazon’s control over the Australian bookselling landscape, their exploitation of human rights, and the sheer excess of their book discounting, it is unconscionable to keep supporting their practices. Legislation must be drafted to halt Amazon’s offensive, regulators need to step in, and in the meantime, let’s stop giving them our money.