I have long maintained that, with the exception of Arrival (which you should definitely watch), language is tragically underexplored in film. However, although it may not be the subject of many films, there is actually a lot to explore when looking at how language is represented onscreen, especially in the realm of translation. How do filmmakers translate dialogue between languages, or deal with multilingual scripts? How do they cater to a range of audiences, and how do they deal with languages that no one, in any audience, speaks?

Dealing with multiple languages in film is tricky. Filmmakers may run into the issue of translating in several contexts; they may depict characters who speak different languages to each other, or may have to translate their film into another language so that foreign audiences can consume it too. The most common method for this, from what I can tell, is subtitling, either for the entire movie or just for the parts where a non-dominant language in the film is being spoken. This isn’t perfect. Some audiences find it difficult to split attention between reading and absorbing information on-screen. Furthermore, these translations can fail to capture the nuance encoded in a script. When culturally-specific or semantically encoded nuance is poorly translated, audiences can miss out on plot-relevant observations and development, as well as beautiful writing. Squid Game was criticised for its English subtitling for this reason. Dubbing, or recording translated dialogue over the top of the original audio, also suffers from this, with the additional loss of the vocal performances of the original actors. There seems to be no perfect way of translating for film.

This may be why, then, many filmmakers ask viewers to suspend disbelief when thinking about language in film. Many films set in non-English-speaking contexts are told wholly, or at least in part, in English: The Woman King, Les Miserables, and Mulan, for example, are all told with varying levels of commitment to linguistic accuracy of the context they occur in. The most egregious example of linguistic “movie magic” I can think of is Disney’s Pocahontas, within which Pocahontas and John Smith, both speaking English in the film, are implied to have a language barrier until they learn to listen to each other “with their hearts”. Contextually inaccurate language use makes a film more accessible to whichever audience speaks the language the filmmaker chose, but it is still an imperfect solution. It creates audience aversion to subtitling, which makes it hard for non-English films to succeed in the mainstream (although there has been a recent pleasing upswing of non-English box office successes like Parasite).

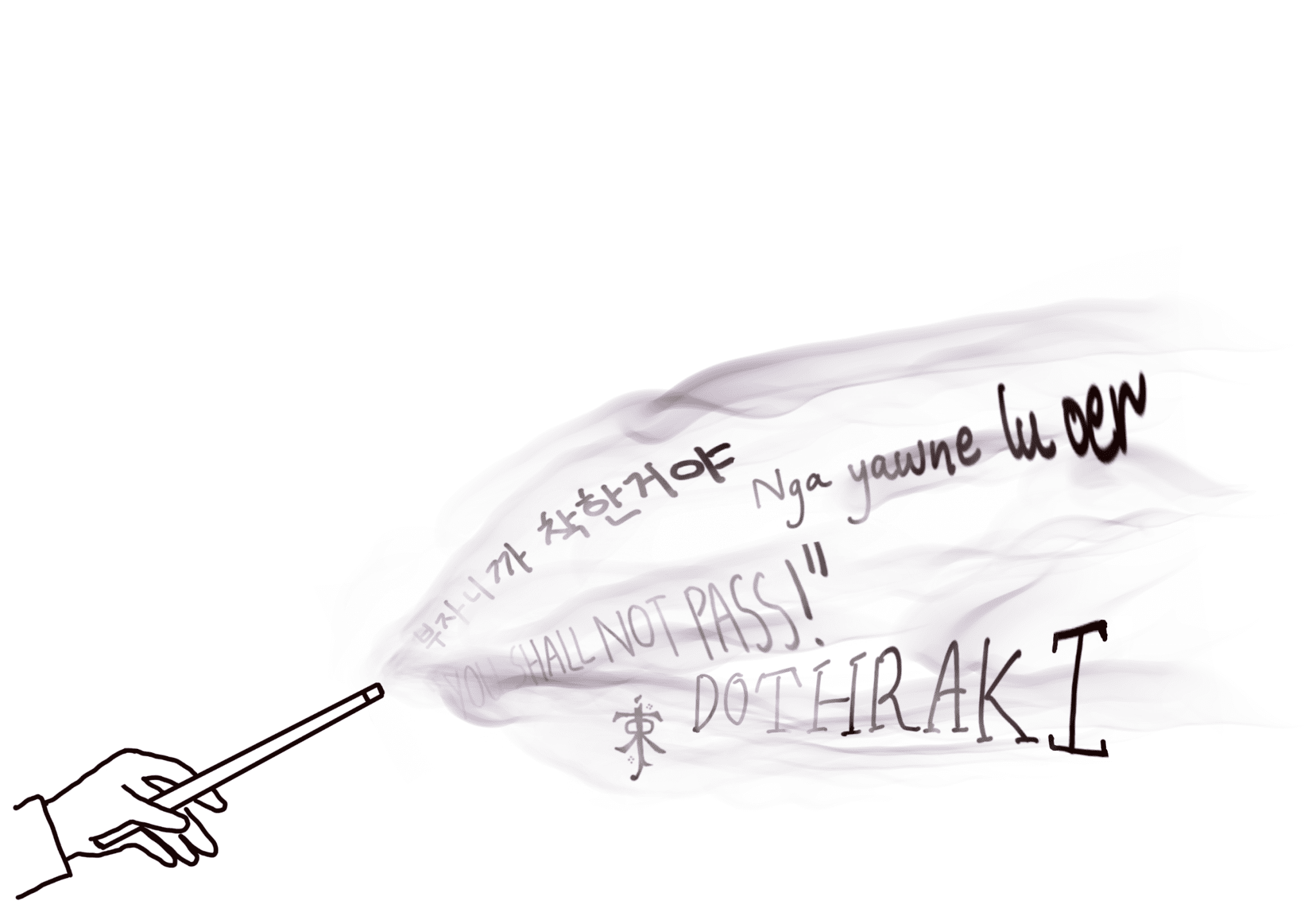

With this in mind, translation can be more of an obstacle a director has to overcome than anything else. Despite this, many films go beyond including multiple real languages in their scripts, and opt to incorporate made-up language into their storytelling. These fictional languages are called conlangs (constructed languages). Famous examples include Klingon from Star Trek, Dothraki from Game of Thrones, and Na’vi from Avatar. Although it is not necessary for alien or fantastical speech to come from a comprehensively thought out language, filmmakers can hire linguists to develop grammars of conlangs for the purpose of consistency within its use in the film. In the cases of well-known conlangs, like the ones I listed above, enough work has been done on these languages to learn to speak them yourself. You can even learn Klingon and High Valyrian on Duolingo.

Despite this possibility, the odds of your audience having any understanding of what conlangs mean without subtitling are negligible. So, why go to the effort of creating a language, only to have to translate it back?

There are several possible reasons. The most intuitive reason, to me, is immersion. The world is a multilingual place. If there were life forms on other planets or in different realities, there’s no reason they wouldn’t also be multilingual. Cross-cultural contact in space ought to have all the linguistic barriers that cross-cultural contact on Earth does. If you are depicting distinct fantastical cultural groups or species, having one speak a conlang is an effective way of making them distinct from one another. It can be a tool for in-group communication on screen — Legolas and Aragorn can discuss their plans in Elvish in front of men who don’t speak it, cluing the audience into something that the characters are oblivious to. Having this linguistic diversity makes worlds seem more real.

Beyond that, the sounds of conlangs can also be evocative and immersive. There are a finite number of consonant sounds a human mouth is capable of making, but no language uses all of them. Drawing on sounds that fall outside of an English consonant inventory, for example, can make a conlang sound especially alien. Perhaps predictably, using consonant sounds as a shorthand for certain traits that a writer may wish to ascribe to an alien culture — brutishness for orcs or sophistication for elves, for example — can be fraught. “Black Speech”, the language Tolkien wrote for Orcs and other evil creatures in Middle Earth, is incredibly laryngeal, with a lot of consonant sounds clustered at the back of the mouth. Some of these sounds can’t be found in English, but can be in languages like Arabic. In contrast, languages that are meant to connote elegance and sophistication are more likely to borrow sounds from Romance languages. The associations that we have with sounds, for better or worse, tell us about the fantastical characters that speak them.

Language is an integral part of storytelling, in the most literal sense possible, as well as more poetically. Although it can pose an obstacle to audience accessibility, it can also enrich stories in their nuance and believability. Translating is an art form, and even though it can prove challenging, it transforms the media we consume in a really significant way. And I, for one, think that’s kind of magical.