I would like to begin this review with a conclusion. Put simply, Eleanor Catton’s Sydney Writers’ Festival talk left me with one resounding reflection: conversation is so essential to the way we tell and consume stories. Both privately and collectively, the conversations that the event facilitated affirmed the importance of in-person events, and the intimacy that Catton forged with her audience.

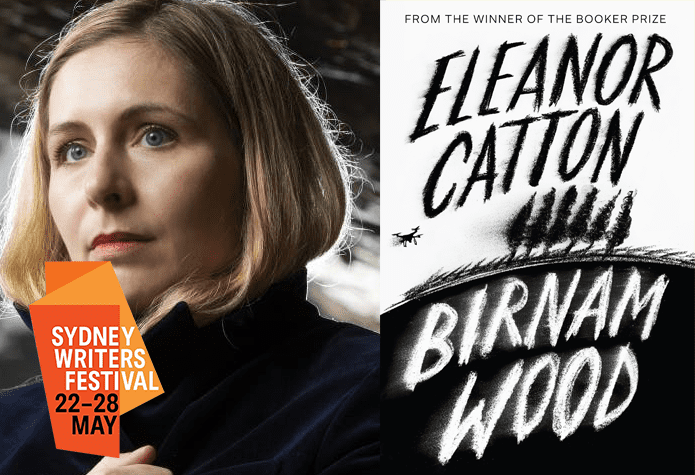

Eleanor Catton, the youngest-ever winner of the Booker Prize, and writer of the complex and expansive The Luminaries, was interviewed by BeeJay Silcox.

Silcox, a writer herself, warmed up the audience first with anecdotes of her mother’s eccentricities and jokes about the correct way to drink Milo — both of which prompted appreciation from the audience, and set the tone of the conversation to follow.

As Catton began to speak, introducing the audience to Birnam Wood, her latest novel, and how it differs from its famed predecessor, Silcox’s questions complemented the discussion effortlessly. Catton would often pause after being questioned, commenting, “What an interesting question to ask,” before beginning to unravel her response, laying it out eloquently for the audience. One reflection she made has haunted me since (in the best possible way). Catton drew parallels with the algorithms on our phones and psychopaths. Both appease, manipulate and guide you to an outcome. Both are sinisterly subtle and undeniably ubiquitous. This kind of insight was emblematic of others to come: ruthless in their intelligence yet accessible in their relatability to a shared twenty-first century experience.

As an audience member, I got the impression that the conversation between the two writers challenged them both, as a discussion should. They raised ideas the other hadn’t thought of, and prodded each other to go deeper. And where they went was fantastic.

Eleanor Catton would often come back to the ills of our time: social media, pervasive surveillance, villainous public figures and the destruction of our ecosystem. Birnam Wood is a novel in conversation with these challenges.

Crucially, however, Catton emphasises that, as an author, this conversation is not a dogmatic one that intends to impart upon the reader her personal doctrine. Instead, Catton tells the audience that “a job of a novel is to be a good novel”, and not to be an act of political ventriloquism from the author.

Birnam Wood tells the story of a billionaire wishing to build a bunker to protect him from apocalypse, and the climate activist group that seeks to combat this. Described as a simultaneous comedy, tragedy and thriller, the novel switches between alternate perspectives from a range of characters. Catton fully expects readers to enter this novel with their own political convictions, on which character is correct, and which is reprehensible. She hopes, however, that by the end, these convictions become muddled.

This wish is indicative of Catton’s desire for debate and conversation.

“There are so many debates — but who is actually debating?” Catton asked. She referred to the nature of partisan politics, where the two opposing sides each bear distinct arguments, supporting evidence and staunch defendants. Each is so confident they are correct, and that there is nothing to gain from discussing, that they refuse to engage in an argument. Facing biassed media and echo chambers, Catton criticised the contemporary tendency to sit comfortably only with those you agree with.

I shifted in my seat at her comment. How frequently do I refuse to debate the other side, believing that any argument is pointless? I recalled family friends dismissing feminism as a thing of the past, and taking another sip of my drink, instead of disagreeing with them over the urgency of activism as my reproductive rights are being eroded. Her urge to debate simultaneously ashamed and inspired me.

By crafting a novel that forces readers to be deeply implicated in the minds of her characters, she demands that her audience wrestles with other perspectives. We inevitably enter a reading with our own beliefs, but Catton hopes that we can use that to our advantage.

As such, Catton champions comprehensive conversation. Fluently connecting with the audience and Silcox alike, Catton’s Sydney Writers’ Festival left audiences with a desire to communicate — with themselves, morality, good books, and good conversations.