I am white. As a kid, I was told that racism is evil, and that everyone is the same, regardless of their skin colour. This framing of racism is a simple one: if you, a small white child, refrain from being cruel to your classmates, you are doing the world a favour. Good for you! With age, though, this framing starts to fall short.

The term “white fragility” was coined by author Robin DiAngelo in 2011. According to DiAngelo, “White Fragility is a state in which even a minimal challenge to the white position becomes intolerable, triggering a range of defensive moves including: argumentation, invalidation, silence, withdrawal and claims of being attacked and misunderstood.” To better understand this, I spoke to a range of POC, who I refer to throughout this article.

Existing in a world that treats you as a priority can predispose white people to feel entitled to priority, and to feel threatened when that priority is re-allocated. This can look like moral panic in response to affirmative action policies, escalating as far as the US Supreme Court’s decision to bar universities from having such policies. Annie tells me that she has experienced backlash from “old white men who are used to having the world conform to them” when doing something as simple as getting on a train before them. She pointed to the trope of a “Karen” — an older white woman who throws a tantrum when she doesn’t get what she wants — as an illustration of how common this entitled fragility is (albeit an imperfect one with sexist implications).

For many white people, it is very easy not to identify with this type of fragility. It’s tempting to think of Karens and old white guys as a unique brand of white people — entitled, ignorant, probably conservative — that we, young, progressive white people couldn’t be less like. After all, we recognise our privilege. The issue, though, is that the bar to clear to have “recognised” something is incredibly low. Recognising just means “identifying”; it does not entail anything further. White fragility is very much prevalent within leftist and progressive spaces; if anything, this identity of progressivism can cause white people who are called out for their whiteness to double down — to be more fragile.

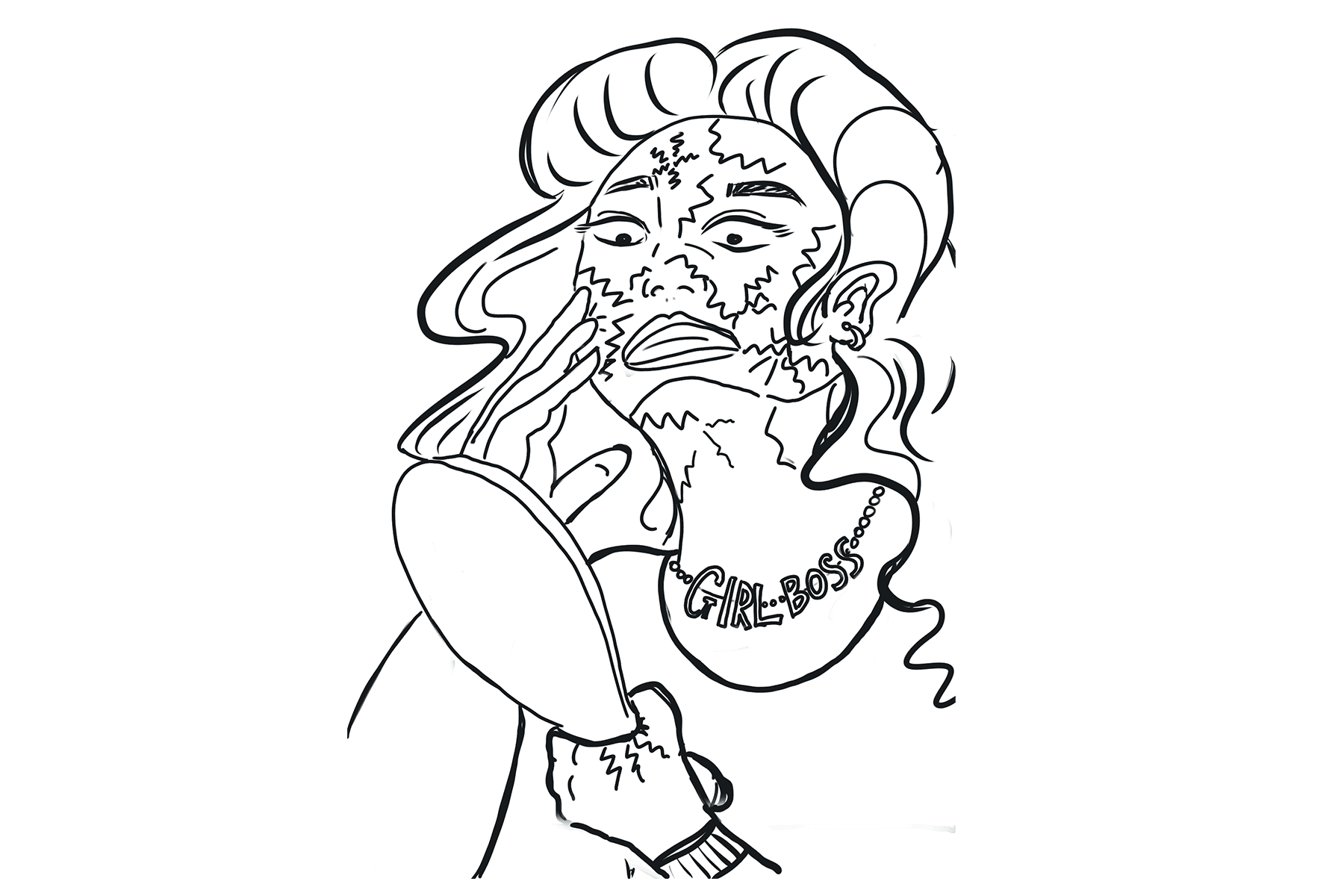

White fragility can result in the equation of racism to other forms of oppression. Multiple interviewees pointed to their own experiences with queer white people or white women downplaying their privilege by insisting that they can relate to the struggles of being discriminated against. Sujin describes it as “annoying” and a “petty competition”; Mehnaaz (in meme format) describes other “axes of oppression” such as queerness as bandaids with which white people use to cover their “white guilt”. In a binary between whiteness and POC, whiteness is, categorically, oppressive. Most white people don’t see themselves as oppressors, either because it is an abstract category with extreme traits, or because, as three-dimensional beings, they likely experience some hardship or oppression themselves. Introducing other axes of oppression is a misguided attempt to de-pedestalise oneself for fear of being cast as a villain. No matter how many other ways a white person is oppressed, they still benefit more from white privilege than a POC does — to downplay that is dishonest.

This deflection derives from the underlying tenet of white fragility: defensiveness. “White people get SO defensive when called out,” Mehnaaz explains, “it often really freaks them out to hear that they are also doing things wrong or can change.” This defensiveness is often born of a fear of being labelled racist. This fear can snowball into active harm: one interviewee described being a part of an activism group led by a white organiser who got so defensive when POC suggested that certain elements of their activism weren’t culturally sensitive that it became “no longer a safe community space”. Constant defensiveness — challenging POC on their interpretations of an action as racist, insisting that they cannot be racist, and shaming those who call them out — is actively harmful. It punishes POC for speaking up about injustice and forces them to console white people, all while continuing to suffer from racism. “Recognising” privilege means nothing if that doesn’t also involve reckoning with it.

Throughout this article, I have struggled to choose between first and third-person pronouns when describing white people. I relate to the fears which I have described in this article; I desperately do not want people to think that I’m racist. I have friends who are POC who I would hate to hurt or isolate. I have seen them hurt by systems which I profit from. I’ve heard countless rants about how dumb white people are, and have sat there, nodding, as though I can relate. Even now, writing this, I struggle to attribute my defensiveness to anything but a desire to be inclusive and thoughtful. In reality, though, that isn’t true. This defensiveness stems from the assumption that, unless I make it abundantly clear, the POC in my life will assume that I am racist. This is silly. It presupposes that I am the main character, that all the POC in my life need to be told whether I am racist or not, and can’t work out for themselves that I’ve grown up as a white person with white privilege and I’m doing my best. Of course they can.

Robin DiAngelo, author of White Fragility, is white. When I pitched this article to my editors, Misbah said, “white people should be more critical of whiteness”. The burden that white people have — that I have — should not be to simply recognise their privilege, but to interrogate it, to wring it out like a wet towel and see what drips out. “I wish white people were okay with taking on that lil discomfort for the greater good,” Aleina explains. Discussions about racism should not be dominated by white people trying to prove that they aren’t racist, but by POC, who know what is racist. “So many white people are allergic to listening,” Mehnaaz tells me. “I don’t need a speech on how lucky you are. I just need you to know when to stop speaking.”