Every feminist who critiques the media is familiar with the Sexy Lamp Test. It’s like the Bechdel test but cheekier. If you can replace a female character in a story with a sexy lamp, and it has no effect on the plot whatsoever, the movie fails the test.

This test is an attempt to illustrate that although there has been a demand for media to be more diverse and representative, merely adding a character with a particular identity on top of a pre-constructed story does not do the job. Using these tests to critique media that has classic heteronormative and white American tropes would be to pick the low-hanging fruit, in my opinion. The target audience for that media is not people with progressive leanings, and examining media that comes in progressive wrapping is much more crucial.

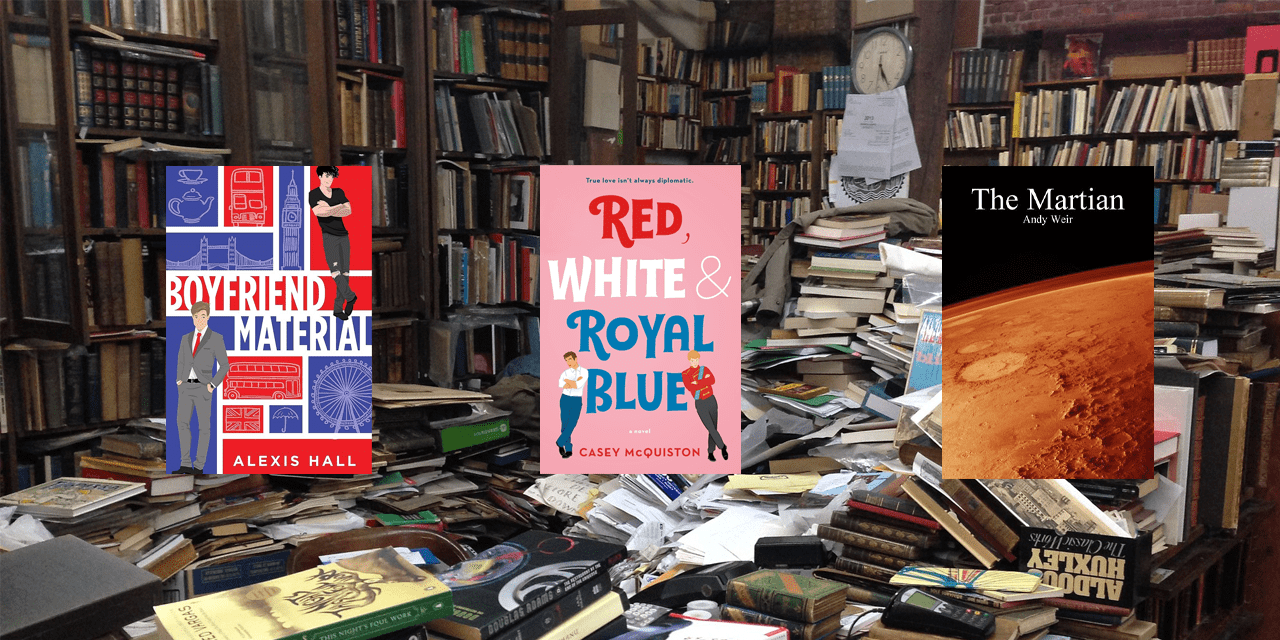

Alex Claremont-Diaz, one of the protagonists of Red, White and Royal Blue, a recently popular queer YA romance, has, as his name suggests, Mexican heritage. In the book, it isn’t as if his identity isn’t mentioned, in fact, it’s talked about reasonably frequently. But the exploration of his identity is all external. It’s about how his identity would affect his ambition of being a politician, how it currently affects his mother’s political career, and how it would impact his coming out to his dad. It’s the way a white person thinks of a non-white identity. Only relevant in certain spheres, and mostly a disadvantage they are shackled by.

Non-white identities do not exist to be perceived by and responded to by white people — they come with cultural values, traditions, and experiences. Culture is far more than what race you tick on a census and how homophobic your parents are, it’s something that shapes every aspect of how you interact with the world; what you do in a day, how you structure your life, what you value and how you try to obtain what you value. It’s also how you relate to other people and build relationships with them.

Alex’s heritage plays no real role in his story, or the plot of the book. He was functionally white. A white character could have replaced him and, if you took out a couple of pages of hamfisted dialogue referencing his heritage, nothing else in the book would need to change. You do not need monologues exploring the specific complexities of being a person of colour, but the presence of his identity needs to be a constant lens through which he sees the world, and not something that is just brought up when he randomly speaks Spanish for a bit or is cooking a Mexican dish.

Another popular queer YA romance, Boyfriend Material by Alexis Hall, has a South Asian sidekick named Priya. As I was reading the book, I was enjoying her presence in the parts she showed up in, until about halfway through when she discloses that she does not eat pork. There were alarm bells ringing in my head already, but I was willing to make myself not pay them attention. But the author goes on to double down and make the whole conversation about why she doesn’t do so, and it turns out to be because of her family’s religious beliefs. At this point, any plausible deniability I could have afforded the book was out of the window; the author clearly intended Priya to be a Muslim character.

The problem was that Priya is a very Hindu name. Just because a name sounds South Asian, doesn’t mean it’s appropriate for every community within South Asia; there are a thousand subcultures, religions, and communities within the one subcontinent, and names work very differently in each. Names have cultural value — South Asian parents don’t just name their kids after the country they went honeymooning in, or after randomly-picked words from other languages they liked the sound of. You won’t find Muslim parents in India naming their child Priya, because they want their child’s name to represent her identity, and be meaningful to her, instead of just being meaningful to them. If the author had spent five minutes googling “Muslim South Asian Girl Names” instead of “South Asian Girl Names” this wouldn’t have happened. Or, they could have just talked to one South Asian person to check before they published their book, but that’s asking for too much really. The reason it is specifically bad for queer romances to do this is because not only are they profiting from selling themselves as progressive: they also have queer youth flocking to them for the representation they were denied in light-hearted, feel-good romances for people their age until very recently. But queer people of colour shouldn’t have to pay this price. They shouldn’t have to sacrifice the representation of one aspect of their identity for another.

The problem isn’t limited to Queer YA authors, though. Andy Weir’s The Martian (which isn’t queer or YA or a romance) also commits a similar crime. The book has a character named “Venkat Kapoor,” which is an incredibly jarring name if you’re from South Asia. “Venkat” is a very common name in South India, and South Indian cultures and languages (Telugu, Tamil, Malayalam, and more), all have meanings associated with Venkat. “Kapoor”, on the other hand, is a very North Indian, Punjabi surname. Those two names do not mix — you can clearly see that the author just Googled popular Indian first names and popular Indian surnames and mashed their favourite results together. You will not find someone named Venkat Kapoor in India. Even if you had parents from each of those cultures, they would not name their child that. Because firstly, the process of naming your child varies from culture to culture (for example, in some South Indian cultures your surname is your father’s first name), and secondly, those two names don’t work sonically either. There are a million South Indian first names that would work with Kapoor as a surname, but Venkat is not one of them. That name just sounds like cacophony.

The problem is that culture is still understood only superficially in white/Western society. Non-European white countries have it even worse because they are so new and removed from any history that they don’t even have the mechanism to understand how culture actually functions and what role it plays in a person’s life. It is still thought of as an add-on, as an ornament that you can simply pick up and wear. Something external to a person’s being. Something you can understand just by looking at it. Like colourful clothes, spicy food, or yoga asanas.

The second problem, one that is more immediately fixable, is that most of these fiction authors just also do not care. They are willing to put in the time and effort to research what they consider relevant to the story and to their body of work, but having diverse and representative characters is not something they genuinely care about, it’s something they do to give their work a progressive packaging and make it sell. We need to be demanding better, and we need to be calling them out when they do ridiculous things like these.