The Women’s Liberation Movement of the seventies has a somewhat confused place in our cultural memory. Instinctively, we might think of certain images: bra-burning, free-love hippies or dissatisfied suburban house-wives, perhaps recognisable figures such as Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan, Simone de Beauvoir or Germaine Greer. Some think of its connection with other distinct yet interrelated progressive movements; anti-Vietnam, Gay Liberation, Civil Rights or environmentalism. Or, they may associate it with Gough Whitlam’s Prime Ministership. In current feminist circles, this time may be considered the cause of some most insidious inheritances; biological essentialism, transphobia, and the progenitor of ‘White’, ‘Liberal’ or ‘girlboss’ feminism. Notably, the narratives of today either choose to look at this time either to convey feminism’s successes or emphasise its failures.

Yet unsurprisingly, this tendency erases the nuanced and wide tapestry of feminist thinking occuring at the time. The existence of Radical lesbian separatist communities in New South Wales is a history which complicates this binary distinction.

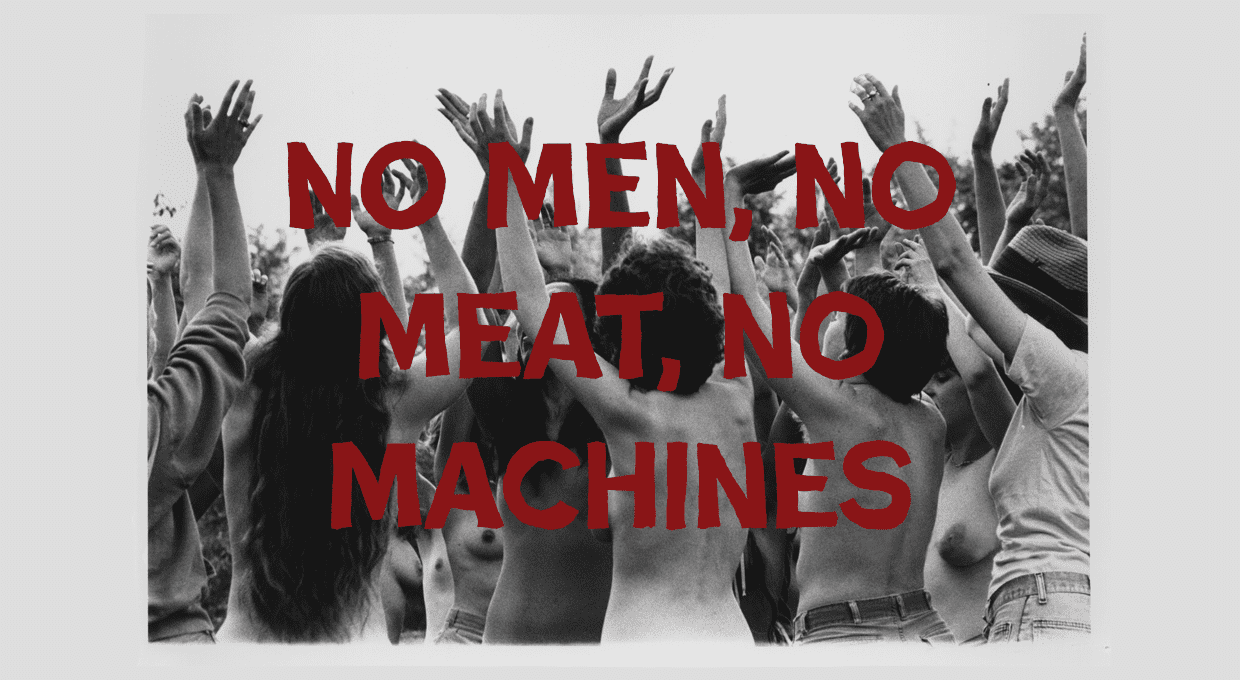

Throughout the seventies, there existed three woman-only regional communities in northern New South Wales which loosely followed the ethos of ‘No men, no meat, no machines’. These communities, named Amazon Acres, The Valley and Herland, were founded by feminists who splintered from urban-based feminist and queer collectives that proliferated in this time, who desired a place in which they could embody their politics in all aspects of their lives. The residents slept and ate communally, mainly practised non-monogamy, spent their days farming only what they needed and made every major decision by committee. Amazon Acres, the most well-known of these communities, was a one thousand acre property of uncleared bushland located near Wauchope that was purchased through donations from readers of feminist publications, such as the Sydney Women’s Liberation Newsletter, many of whom never lived on or visited the lands. The community had only about one hundred people in permanent residency at any one time, yet the land acted as a ‘community resource’, welcoming many visitors from all over Australia. These communities provided a place of refuge for queer women experiencing misogyny in Gay Liberation groups and homophobia in feminist circles. At these farms, women could reject the notion that the Australian bush was a site of “white masculine endeavour” and explore their identities without the threats of a patriarchal society, the toxic influences of capitalism and the taboos of homosexuality.

The politics these communities espoused are one of the most literal interpretations of the ‘personal is political’. Many residents saw each lifestyle decision as an unavoidably political one. Queer female relationships, in particular, were seen as an opportunity to dissolve socially prescribed sex roles and entirely embrace the notion of sisterhood. The “Radicalesbian Manifesto”, released in 1973, states “fucking with another woman just removes one more barrier in our minds, enables us to learn to love our woman-selves in another woman”. In relation to non-monogamy, the same paper reads: “We have to break down the sanctity of relationships… We believe that the primacy of genital sexuality, the idea that it is a consummation, is a male trick”. Some who subscribed to this thinking were largely unsympathetic to those in relationships with men. One claiming that “until all women are lesbians there will be no true political revolution… feminists who still sleep with the man are delivering their most vital energies to the oppressor”.

As such, many rules were established, yet few could agree on them. The “tyranny of the dissenter” plagued the communities. Some couples choose to remain monogamous while living on the farms, prompting criticism from others for being ‘exclusionary’. While the practice of non-monogamy for some proved complex and fulfilling, heartbreak became commonplace. Some desired to eat meat, remain in contact with male relatives or friends, bring their young male children to live with them, or farm using modern technology. All stances which caused significant debate. A political lens of today exposes these contradictions even further. As the exploration of female and queer identities were emphasised, considerations of race and class were largely ignored. Many would not have had the financial freedom to relocate or travel to the farm, making Amazon Acres a ‘community resource’ to those with expendable income. While occupants rejected the notion that the Australian bush was a site of “white masculine endeavour”, inclusionary of women, further acknowledgement of this as a colonial activity was never made. Nor was there an acknowledgement of their use of unceded Indigenous land.

As the eighties progressed, the energy that these communities formerly had began to dwindle. Many became tired of the disagreements and the harshness of an Australian rural climate, eventually desiring autonomy and privacy, increasingly choosing to sleep and eat alone, enter into monogamous relationships or embark on careers which required relocation to urban centres. However, Amazon Acres in particular lives on, remaining in the ownership of the collective.

As we wrestle today with tackling many distinct yet interrelated injustices, it’s both deflating and encouraging to see how many were exploring these same questions some fifty years ago. With the notion of intersectionality, we now have a more comprehensive vocabulary for marrying numerous schools of progressive thought, and yet face many of the similar challenges that the residents of Amazon Acres, and other communities experienced. While few have an adequate answer to how we can ‘fix’ these issues, this history encourages us to take a more nuanced approach when we look to the past, being sure to acknowledge its failures, as well its successes.