It was only in 2019, when Les Murray passed, that I discovered I was related to a poet. My granddad, Pa, grew up on a dairy farm three miles from Krambach, a village on the mid north coast of NSW. Not far off in Bunyah, lived his cousin, Les. They were both born in Nabiac hospital, only a day apart in October 1938, and attended Nabiac Primary School together. Les was considered Australia’s unofficial poet laureate. He published nearly 30 volumes of poetry, two verse-novels, eight prose collections and five edited volumes.

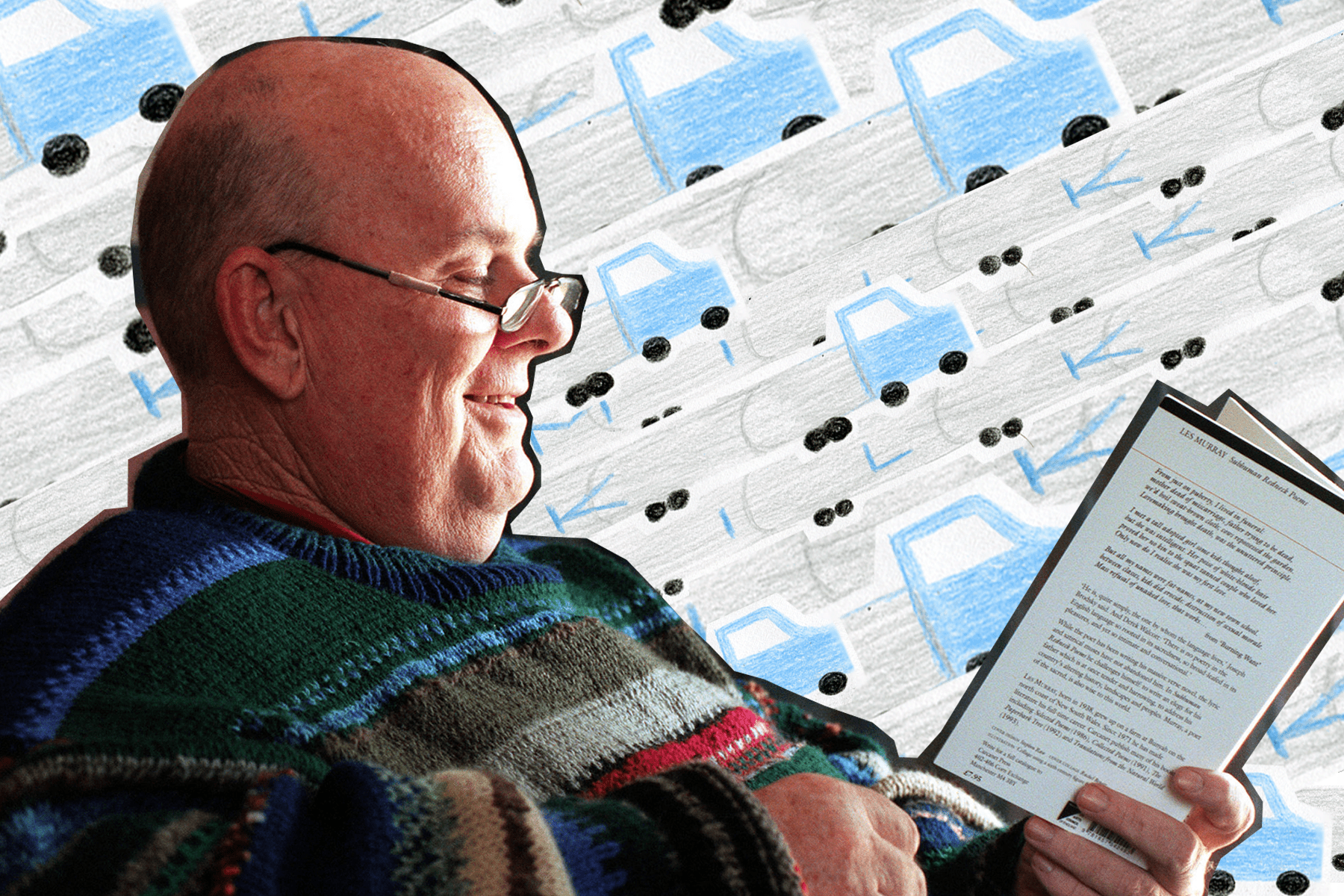

A stack of Les’ work sits on a shelf in the Taree home my grandparents moved into just over two years ago. A copy of Les’ New Selected Poems that he gifted to Pa on his birthday sits atop the pile, and scattered amidst the various collections are newspaper clippings of Les’ poems published in the March 1998 issue of the Quadrant and articles commemorating Les’ life and memory in The Manning Community News.

As I’ve devoured more of Les’ work since his passing, I find myself not only learning more about Les’ life, but my grandparents’ lives too. A mentioning of the poem, “The Milk Lorry”, turned into an excited retelling of the countless times Pa would hitch a ride on the back of the milk lorry whenever he missed the bus to school. He shuddered as I read out an excerpt from Blood and The Cows on Killing Day, as he remembered the gruesome reality of the days before abattoirs when you had to kill your own livestock. He smiled nostalgically as I read out The Disorderly, where the thought of being sixty-two in the year two thousand was unimaginable.

“He was a gentle sort of fellow,” my grandad said one afternoon as he showed me the tomato vine he planted just the week before. “He was often bullied a lot in primary school because of his size. They’d punch his arm and he’d just take it and not do anything… I got into a lot of fights at school to stick up for him.”

Les attended the University of Sydney on a scholarship in 1957 where he met Geoffrey Lehmann and Clive James, who would become his close friends, as well as his writing and editing partners and confidantes. Les wrote and edited for Honi Soit, as well as Hermes and ARNA, annual literary journals at the University. It was here where he could finally study the arts and languages, or rather the “glamour subjects” that never came his way as a kid.

Pa spoke of Les’ love of language with fascination, pride, and a hint of regret. While Les’ genius meant he could afford to skip countless schooldays and not fall behind, the thought of Les spending most days alone reading by the creek saddened him.

“After his mother, Miriam, passed from a miscarriage when Les was twelve, he only had his father, Cecil, to talk to,” Pa said. “He was quite isolated.”

Grief and guilt consumed many of his poems. As I read “Burning Want” and “The Last Hellos” aloud, poems about his mother and father’s death respectively, the comforting silence that often filled my grandparents’ country home shifted; not out of discomfort, but in commemoration and contemplation. My grandma, Mardy, spoke of her sisters’ deaths and Pa spoke of his father’s.

“An Evening in Bunyah” from Les’ first poetry book, The Weatherboard Cathedral, is my granddad’s favourite poem. He spoke with his hands as he recounted Les’ descriptions of the “shabby house” he grew up in and the rain and light that would sift through the cracks.

Les’ work has become a new entryway into my grandparents’ lives. Poetic vignettes of wildlife in the bush have welcomed stories I could never imagine, like the time my grandma quite literally killed and chopped up a snake with a shovel to protect my aunt who was sleeping in a bassinet nearby.

“It was the most awful feeling,” she said. “After I did it, I rang Pa and then poured myself a stiff whiskey.”

I’ve even found parts of my own life in Les’ poetry through his writings of Sydney and his travels. As he describes the Australian bushland I’ve driven through every year since I was young, I find myself wishing I had the chance to meet him. My younger self remembers the “dream of wearing shorts forever in the enormous paddocks”, the unbearable humidity and the “cool night verandah.” My present self knows “performance”, of “queuing down bloody highways all round Easter”, of saying “last hellos”, lamenting a “forest, hit by modern use” and listening to “birds, singly and in flocks hopping over the suburb.”

I was always at peace in my grandparents’ home. I had clusters of memories from my mum and her four sisters’ childhood to cling onto, and I had memories of my own; lying for hours on the sunroom tiles at Christmas reading old comics and fairytales that had been left behind. Now, I sit on the seat beside my granddad’s nursery, finding equanimity in Les’ poetry. In his friendship with writing and its lyrics of reverie, and in his resurrection of stories from my family’s past.

“In the high cool country,

having come from the clouds,

down a tilting road

into a distant valley,

you drive without haste.”

Driving Through Sawmill Towns by Les Murray (New Selected Poems, 1998)