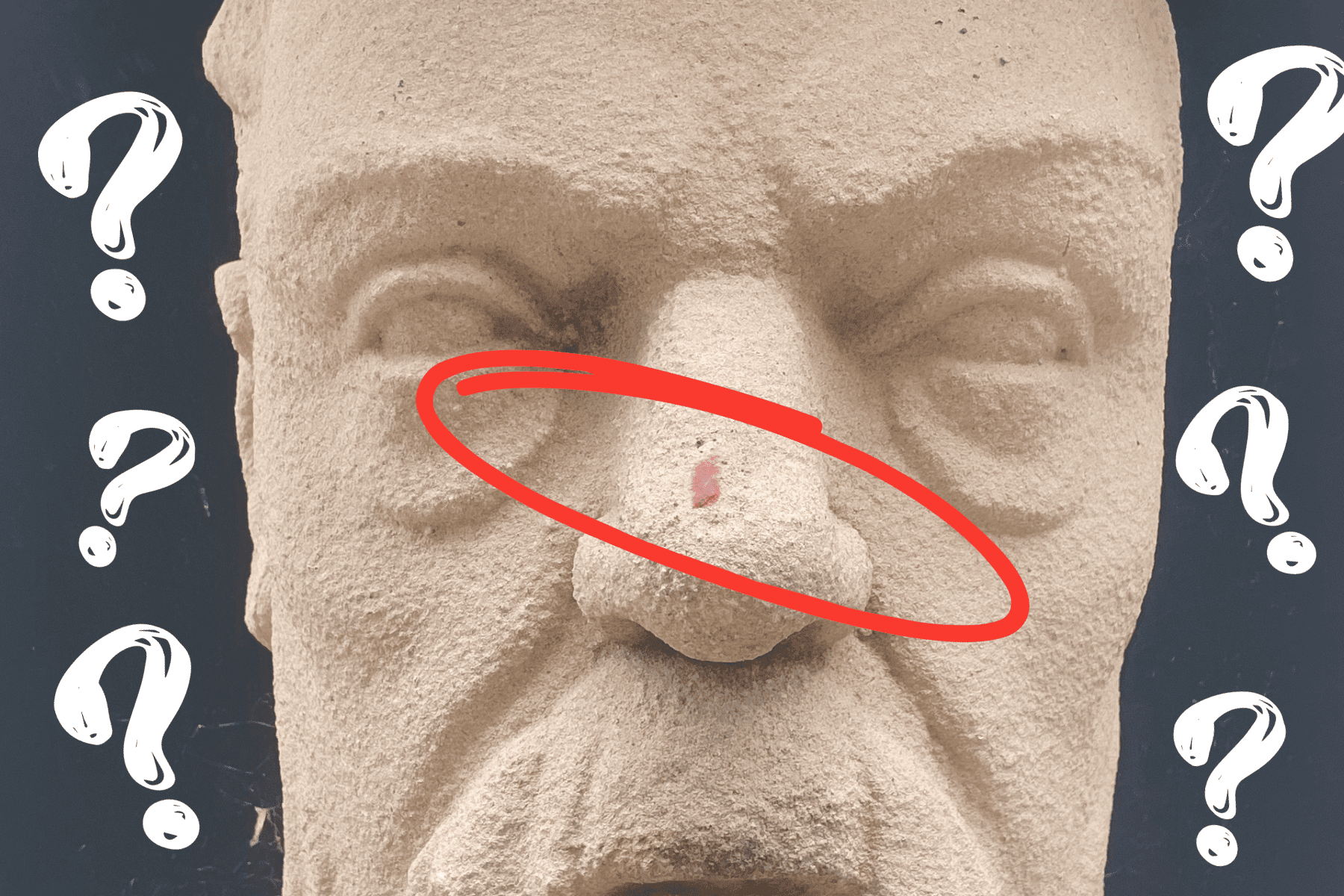

It began with an anonymous tip and ended with a third year chemistry lecture in a desperate attempt to find answers to one question. It had plagued me since it was brought to my attention, a campus conundrum that I had no answers for — what on earth is the substance on the statue outside Susan Wakil, and why hasn’t it been washed away?

A source, who would prefer to remain anonymous, told Honi “I came across the stain when I moved into my new role in mid June of this year. Not knowing who any of these sandstone busts were supposed to depict, I initially thought that this particular individual happened to have a rather prominent red blemish, but I thought it was odd (and maybe a little cruel) that they’d go to such effort to use a different material for it.”

“On closer inspection, it had to be something else, like tomato sauce, but why was it so perfectly formed on this one spot?”

Honi decided to investigate.

Commemorating Louis Pasteur, a chemist and microbiologist who was instrumental in the discovery of vaccines, furthered understanding disease prevention, and whom pasteurisation is named after, the statue is one of the last remaining relics from the exterior of the former Blackburn building. Pasteuer became a controversial figure in death, falsely claiming he invented vaccines he didn’t, and testing other vaccines without a medical licence (considered dodgy ethics even during the 19th century). It seems unlikely that this is enough for someone to purposely deface the statue with an unidentified substance some 128 years later.

Pasteur in better, stain free, days outside the former Blackburn building.

Senior Lecturer in Theoretical Materials Chemistry, Associate Professor Toby Hudson, told Honi, “It’s hard to know definitively why a substance adheres better to a surface than others, without knowing the composition or structure.”

Other students Honi spoke to felt the stain was one of two things — either tomato sauce, or bubble gum. An anonymous source told Honi that “Over time, I noticed [the stain] began to drip at an extremely slow pace. If this was indeed tomato sauce, it was significantly more viscous than any I’ve ever come across, taking weeks to move a few centimetres.

“Additionally, there was no sign of mould or any bacterial growth on it, nor had any animals or insects been attracted to it. The typically high sugar content of tomato sauce surely would’ve caught the attention of a fly or ant colony by now.

“I have since passed the blemish each week for the past few months. When I passed by a week ago, it was still there, bright and unspoiled as I first came across it.”

They added the possibility of a third option — blood.

“It being found between the Susan Wakil Health Building and the RPA surely doesn’t mean this is something else… right?” they told Honi.

While preliminary investigations, and copious amounts of true crime consumption, revealed to Honi that the stain was indeed not blood, we were no closer to figuring out what it actually was. This, Hudson told us, was crucial in figuring out why it had persisted for so long.

Hudson highlighted that in adhesion, the surface of the material is just as important as the substance stuck to it, with porous surfaces holding onto stains better than non-porous ones.

“One thing I think is that the base underneath looked a bit concrete-y or a bit sandstone-y. Those are super porous surfaces. So anything that gets in can properly get in,” Hudson told Honi.

With one part of the mystery of adhesion solved, Hudson then turned his attention to what the stain could be. Honi learnt that if the stain was tomato sauce, it would be able to be dissolved. “Let’s say for a moment it was tomato sauce, you’ve washed dishes before, it’s easy to wash up when it’s wet, but difficult to wash up when it’s dry, right?

“So what’s happening there is that the water is evaporating, and that all the organic bits of the tomato and whatever else is in the sauce are now evaporating too.

“But, if it’s bubblegum instead of tomato sauce, this solid does not dissolve. You can wash bubblegum as much as you like, it’s never going to dissolve. That is an adhesion question, whether or not it’s stuck into the material.”

While Hudson told Honi that testing the substance in a lab was too time consuming, he did propose an experiment — if the stain can be removed by water it is likely tomato sauce, if not, bubblegum, or a similar substance, would be the culprit. It was an experiment that Hudson said would be allowed by ethics. With this in mind, Honi took to the streets.

We poured water onto the statue, and worked it into the stain, in an effort to dissolve the stain.

The stain remained.

We tried to pick the stain off with a metal fork.

The stain remained.

The stain had no discernable smell, could not be picked off, and up close, didn’t appear to be gum. With no more senses left to figure it out, and no more places to turn, we put the question of what substance the stain is to rest. Perhaps, not every campus conundrum can be solved, and maybe that’s okay.

Honi is seeking more information on this. If you have any further information on the stain outside Susan Wakil please get in touch at editors@honisoit.com, or via our anonymous tip line, here.