I made my first ever zine years before I knew what a zine was. Whilst the word zine may not be familiar to many, the practice of making them is. ‘Growing up trans’ was a zine I made for my year 7 English class, decorated on now-washed-out pink pages with images of Queer people stuck throughout it printed with my shitty Kmart printer. That zine, despite the embarrassment it now gives me, is a perfect example of what a zine can be in its most basic form — a few A4 pages messily glued together, filled with various drawings and writing. Unedited, unmoderated, self-published.

Years later, when I traipsed down the aisles of the Other Worlds zine fair, I realised that even in the chaos of it all, I still felt the deep sense of safety and connection that I usually only experience in Queer spaces.

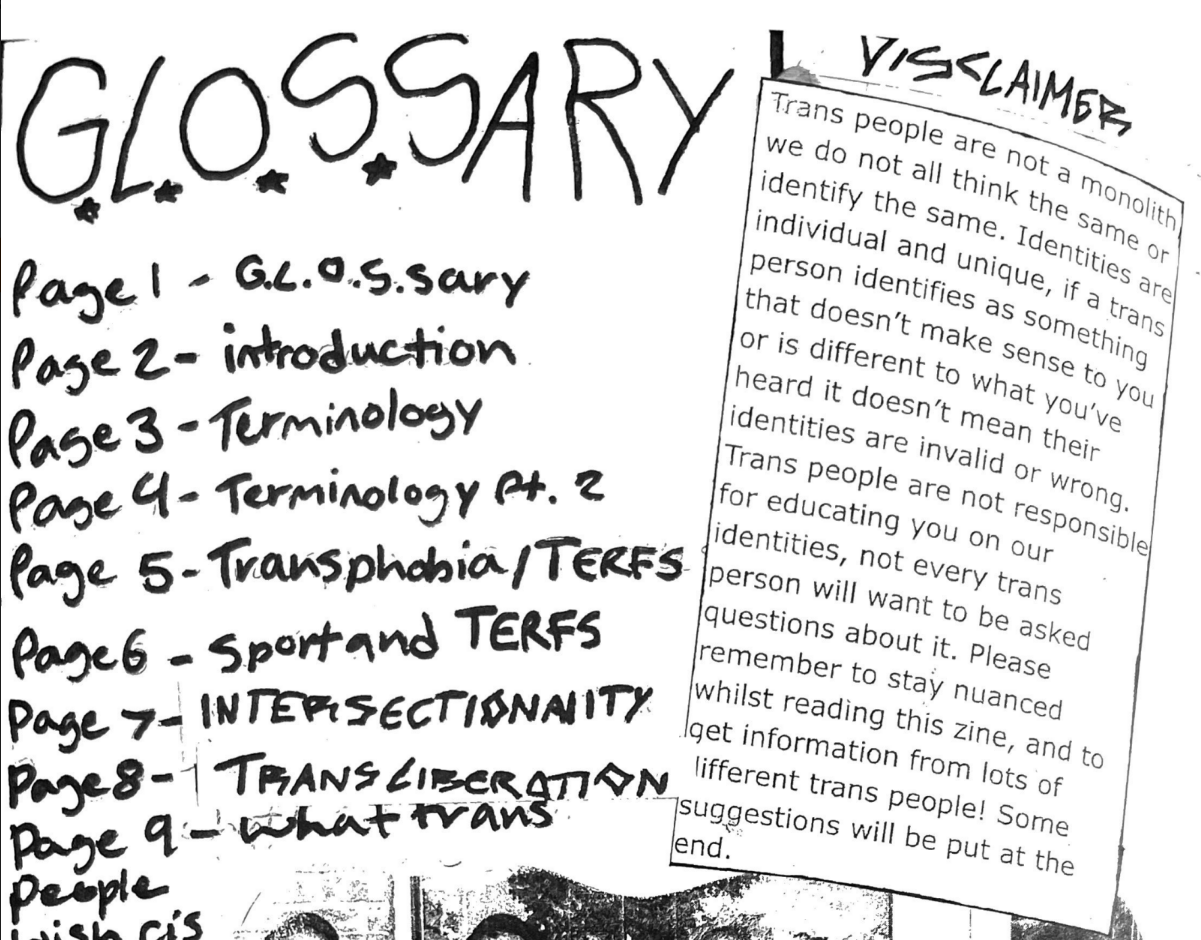

It can be difficult to describe zines to someone who has never seen one because a zine can be almost anything. Zines come in a seemingly infinite number of forms, with one of the only commonalities being the book-adjacent style and their self-published nature. I spoke to fellow zine maker and Queer zine enthusiast Salem (@uhhhsalem) who connected his love of zines to their creative messiness and versatility. Salem mentioned how a person could make a zine that’s a collage of their favourite bugs, and then a zine about something important, like political action, because zines are a visual and physical representation of personal identity.

Zines are an art form that grew out of the pamphlet, which was another early form of radical and/or informational work. Early pamphlets such as Thomas Paine’s 1775 pamphlet “Common Sense” argued for American Independence while Magnus Hirschfield’s 1896 Pamphlet “Sappho and Sokrates” argued that homosexuality was not an illness. Zines follow on from this radical nature of pamphlets, except they often include creative mediums such as poetry, creative writing, or artworks.

Spaces such as the dedicated zine shop ‘The Sticky Institute’ in Melbourne are keeping zine culture alive. I spoke to Liz Egan, a Queer zine maker and volunteer at the Institute, who expressed the intrinsically radical, anarchist nature of zines through their use at protests and pickets. Egan mentioned that zines circulate Pro-Palestine rallies, filled with free information about keeping people safe during political action.

‘Little magazines’ in the 1920’s such as “FIRE” – a zine about empowering young Black artists – and Sci-fi fanzines from the 1940’s were some of the earliest zines to circulate that were more distinct from pamphlets — often by being self-published.

From the beginning, zines gave space to various minorities by allowing these oppressed groups to give themselves the representation that they were denied in general society. Queer zines from the 1970s-1990s emerged from the long standing political legacy of pamphlets and the artistic and radical emerging zine culture. Queer zines were not just a creative outlet, nor an informational resource, but a revolutionary way of connecting and uniting Queers in a time when Queerness was heavily politicised and censored.

As Queerness today is still heavily politicised, modern Queer zines continue the decades-long fight against the censorship of Queerness by portraying authentic and radical Queerness through an art form that undeniably centres radical action, as Egan writes:

“[In the zine community] We’re all outliers. Queer, disabled, neuro-divergent, anarchist punks who are reaching out, buying, and sharing zines in this giant community of creative ‘others’”

Queer spaces today continue to embrace zine culture by including zines as resources in their spaces and hosting Queer zine events. Last year the Packing Room Gallery, then operating from within Sock Drawer Heroes, hosted a group show titled “Zines for zines: celebrate the radical roots of zine publications within transgender communities”. Queer zines hold an integral place in our community as a primary form of expression amongst Queer people.

Searching through many online Queer zine archives (notably QZAP), it is so clear from the zines in the early 2000’s and prior that this was a revolutionary art form for the Queer community. Salem expressed the important role of zines in the Queer community by connecting one another. Trans zines allowed Salem to connect with his community, either through relating to one another or learning about other trans experiences. This is a familiar sentiment shared amongst many Queer people who get a chance to connect with their community through zine making and reading.

Queer zines are inherently radical by portraying uncensored, unapologetic Queerness. According to Egan, the zine community means “being able to connect with someone else’s lived experiences, learn from them, see yourself reflected.”.

Zines from my collection, such as “the sapphic book of feminism”, “memories of girlhood”, “scene qweenz” and “together we can break these chains” all display unapologetic Queerness in various ways: Political avocation, artworks made by trans prisoners, uncensored photos of Queer and trans bodies, and writing about experience. These zines are a few of the hundreds of thousands of Queer zines out there continuing the radical act of authentic Queer representation.