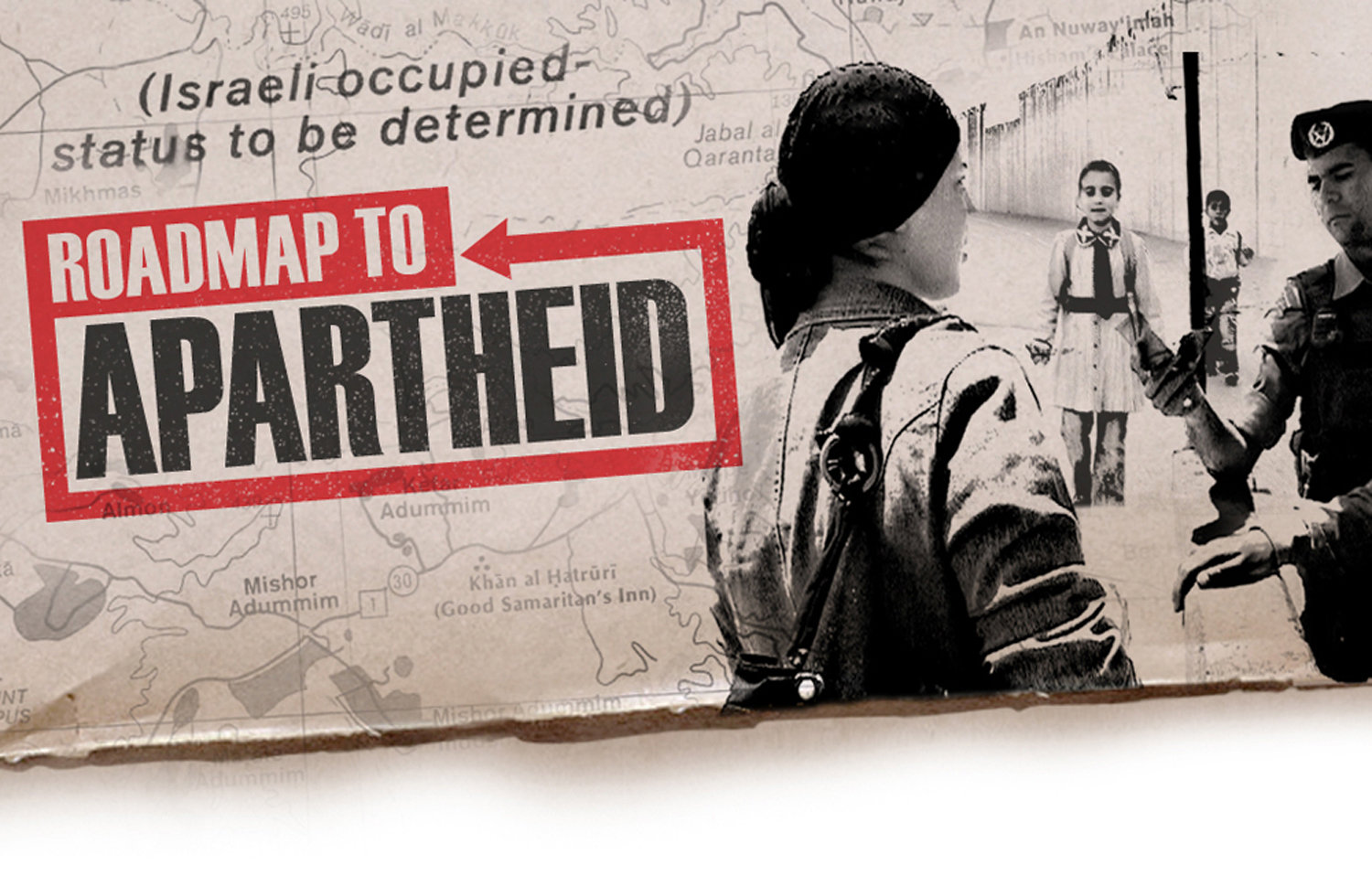

Hosted by the Autonomous Collective Against Racism (ACAR) and BDS Youth, a screening of Ana Nogueira and Eron Davidson’s Roadmap to Apartheid (2012) was held in Manning’s Ethnocultural Space on Monday March 18.

Roadmap to Apartheid — now a twelve-year-old film — provides important corrections to the narrative disseminated by mainstream media outlets regarding Israel’s genocide, comparing the reality of life in Israel, the West Bank and Gaza to the apartheid regime in South Africa between 1948 and 1994.

At the beginning of the film, and continuing throughout, there are powerful visual segments comparing actions in South Africa with nearly identical actions in Palestine. The colonial nature of settlements, the expulsions of indigenous people, the occupation of lands, and the enforcement of separate areas for Palestinians are all well-documented across both contexts.

While Noam Chomsky and Ilan Pappé warn against relying too heavily on comparing Israeli apartheid with South African apartheid, the parallels between the two are unmistakable.

As the film unfolds, viewers see the ways in which the Zionist movement has co-opted the desire for a safe haven for Jewish people, and created a catastrophe for Palestinians — through means such as home demolitions, and the denial of electricity, clean water, work permits and medical care used to weaken the Palestinian population.

Furthermore, checkpoints that hold up traffic and limit travel for Palestinians, along with separate roads for Israelis and Palestinians (superhighways for Israelis, and dirt tracks for Palestinians), make clear the reasons why unequal governance and long-term systemic oppression have continued to inspire Palestinian resistance over the last 76 years.

Indeed, Roadmap to Apartheid’s depiction of the normalisation of daily injustices against Palestinians is intense, exposing the brutality of IDF soldiers (referred to pejoratively as the IOF [Israeli Occupation Forces] in dialogues today), including ID checks and car searches.

The whites in South Africa controlled over 87% of the land (13% of the land for 80% of the population) and described the indigenous Black South Africans as “foreign natives.” In parallel, 90% of Palestinian land is reserved for Jewish Israelis only, with the contradictory descriptor “present absentees” applied to the indigenous Palestinians.

Both terms are antithetical and purely racist. The idea, as described by Ali Abunimah, is to create an “artificial majority” in order to legitimise an illegal occupation.

South Africa demonstrates that BDS is a valid method to counter occupation and oppression and can provide a peaceful means of resolution to the conflict. South Africa’s increasing isolation was, in part, due to the British boycott movement, which promoted a boycott of South African products in order to weaken its economic system. Beginning in the late 1950s, it would take roughly twenty years before the rest of Europe joined the boycott, and around another decade before apartheid in South Africa ended.

Ultimately, the film offers hope, describing the rapid growth of the BDS movement today — far more rapid than the boycott movement of the 1950s.

Roadmap to Apartheid doesn’t offer a clear roadmap to peace or an end to the Israeli occupation, and perhaps it shouldn’t. But it does demonstrate the power of mass-mobilisation of people and international solidarity to pressure governments to cede power and right wrongs.

Israeli Apartheid Week events were organised by the Autonomous Collective Against Racism (ACAR), Students for Palestine, and BDS Youth.