Warning: Spoilers ahead for Saltburn and Harry Potter

When Chistopher Hitchens visited a California bookstore in 2007 to pick up a review copy of the Deathly Hallows, he was shocked by the hundreds of children wearing black gowns, and the stalls proclaiming, “Get your house colours here!”

To him, he was not just witnessing a cultural phenomenon but a practiced and prolific homage to the Anglophilic nature of our popular culture. The “dreams of wealth and class and snobbery,” as Hitchens put it, were built into the fascination with sandstone universities and the sealed letters dropped from above by a parliament of owls that invited you into them.

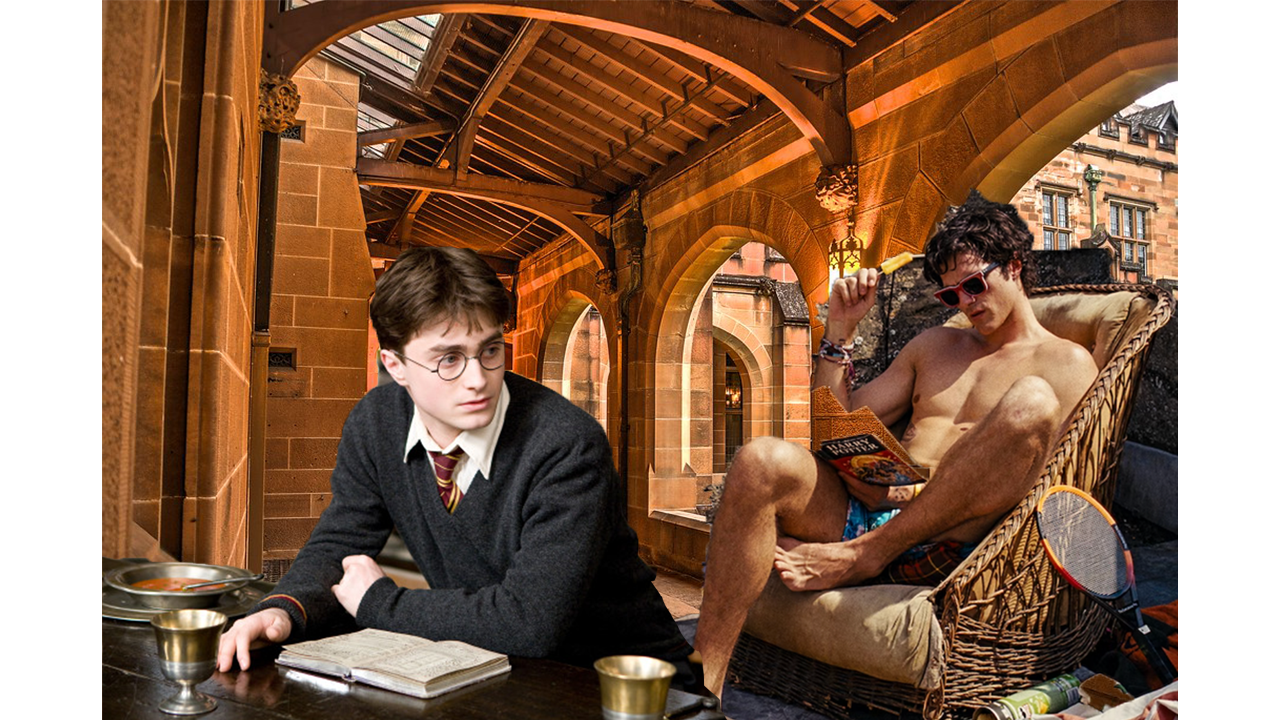

Set in the same year, Saltburn is a partially self-aware contributor to this tradition. At one point, Elordi’s character Felix Catton can be seen reading the final Potter book, while the Saltburn mansion looms in the background. Oliver Quick’s hedonistic fascination and repressed anger at the Catton family, which later transitions into a bloody rampage, reflects how the average person has looked at Oxbridge and the Mansions, compared to the students going back home for centuries. The speculation on how the other half lives has driven a classist literary tradition that ‘may’ poke fun at the aristocracy but also give them an undeserved ritual power.

The first mainstream novels romanticising the life of the Anglophone upper class began in the early 19th century. Thomas Hughes’s Tom Brown’s School Days and Kipling’s Stalky & Co were both bestsellers set in old English public schools. The plots follow adolescent boys as they become ‘men’ in an environment dominated by bullying, sport, and a traditional liberal education filled with Latin classics and English history.

Australians were not immune from the glamour either. The Australian Common Reader tracks reading habits of mostly working-class Australians between 1861 and 1928 using circulation records from six mechanics institute libraries statewide. Miners and Homemakers were the most popular borrowers. Rather than reading novels closer to their experience, they too become trapped in Anglophile chains.

The third most popular author, ahead of Charles Dickens, was Henry Rider Haggard, a Conservative election candidate who wrote novels like King Solomon’s Mines (1885) which follows young British explorers as they ‘discover’ parts of Africa. Even when there was a book on the list which prominently featured the working class, like Silas Kitto Hocking’s Her Benny, which follows the lives of Liverpool street kids, it was a morality tale where the young boys cast away their perceived filth and become model workers.

It’s easy to dismiss these types of literature as an escape, however their prominence suggests something much more sinister. A rigid class system depends on the perception that mobility is possible and, more importantly, desirable. ANU Professor Julieanne Lamond argues that “the ostensible aim for these libraries really was workers’ education.”

If that is the case, the workers have been taught that the greatest good is an adolescent boy wearing an oversized tie reciting hymns on the path to becoming an officer. In 1940, when the British empire was seemingly on its last legs, George Orwell noticed that the weekly boys magazines and penny novels that kids bought from London newsstands overflowed with nostalgia for the public school lifestyle:

“It is quite clear that there are tens and scores of thousands of people to whom every detail of life at a ‘posh’ public school is wildly thrilling and romantic. They happen to be outside that mystic world of quadrangles and house-colors, but they can…live mentally in it for hours at a stretch.”

In Harry Potter, that nostalgia is on full display. Revered figures like Godric Gryffindor and Albus Dumbledore have deeply Anglo-Saxon names and Hogwarts beauty comes from its history that readers are deliberately only given a taste of. Even other magical cultures are depicted as largely usurpers. In The Goblet of Fire, also filmed at Oxford, the Beauxbatons Academy of Magic led by Fleur Delacour wear blue hats and sing with birds while the men from Durmstrang, led by Viktor Krum, shout war chants and wear fur coats. Their initial entrance to Hogwarts is almost a procession. Both schools perform for the students before paying respect to Dumbledore. Hogwarts, it seems, and by extension Britain, is at the centre of the magical universe.

In Saltburn, there is some attempt to poke fun at the Oxford staples. In a tutorial, Oliver and Farleigh argue over nothing while a tired Professor sits there mindlessly prompting them to continue. Yet, most of the audience would be lying to themselves if they said they didn’t envy the parties in the colleges like Oliver does.

Orwell points out that in the boys magazines, “the working classes only enter into the Gem and Magnet as comics or semi-villains.” Saltburn takes that to the extreme. Not only can Oliver not handle the pure pleasure of a life at the Catton family home, but he also has to kill them and take what they have. Oliver’s poverty and parental drug problems are all a middle-class fabrication to get his hands on wealth he does not deserve. “As for class-friction, trade unionism, strikes, slumps, unemployment,” Orwell continues, “not a mention.”

In many ways, Oliver resembles the protagonist of The Picture of Dorian Grey who proclaims:

“the only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it. Resist it, and your soul grows sick with longing for the things it has forbidden to itself, with desire for what it’s monstrous laws have made monstrous and unlawful.”

The lavish Midsummer Night’s Dream themed parties and eccentric family members will never be good enough for Oliver because as Farleigh tells him bluntly, “you will never be one of us.” The message to the wider population is clear. It’s okay to have a taste of our world on the page but never okay to enter it.

Hitchens, known for his extreme characterization, summarised the Anglophilia in Harry Potter by comparing the lightning bolts on many of the kids’ heads to the logo of Sir Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists. While there may not be anything inherently wrong or reactionary with appreciating the upper class aesthetic, the assumption that it is inherently valuable is deeply concerning.